Stanton Glantz has a pretty well-established pattern when it comes to criticizing vaping. Sure, he’ll play up the results of bad studies looking for risks of vaping and completely ignore the very important comparisons to the risks posed by smoking, but his most insidious trick is pretending that vaping actually reduces your chance of quitting smoking.

His source for this is a meta-analysis – that he worked on himself, naturally – which claimed to find exactly that. Of course, this was roundly criticized for relying on absurd studies that explicitly excluded people who’d tried vaping and successfully quit (basically focusing on the most resistant smokers by design) and for haphazardly trying to combine studies with different designs, but that hasn’t stopped him treating the results as gospel.

The main thrust of his argument is that most people who vape end up as “dual users,” meaning that they both smoke and vape, and dual users are even less likely to quit smoking than people who just smoke without vaping. If this was true, it would be genuinely concerning, because vaping could really be reducing the amount of smokers who quit. But, it’s Stanton Glantz, so it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that he’s using bad evidence in his desire to paint vaping in a negative light.

But don’t take my word for it: a new study has used UK data to directly challenge his claim, and found that dual users are no less likely to quit successfully than exclusive smokers or people using NRT.

Stanton’s Meta-Analysis

The new study is pretty open in its intent of questioning the meta-analysis from Sara Kalkhoran and Stanton Glantz. This is regularly cited by US-based opponents of vaping, despite all the criticism it received from experts in the field, with Professor Peter Hajek, for instance, calling it “grossly misleading.” It concluded, based on a meta-analysis of 20 studies, that vaping reduces the odds of quitting cigarettes by 28%, and the authors wrote, “As currently being used, e-cigarettes are associated with significantly less quitting among smokers.”

The biggest problem with it (because there are many) is quite a subtle one. In some of the studies included, the researchers only recruited people who were still smoking and asked them if they’d used e-cigarettes in the past. Then the researchers followed up with them a year later, comparing them to the smokers who’d never used e-cigarettes. The problem with this is that anybody who’d tried vaping and actually quit smoking wouldn’t be included in the sample, and so the group is biased towards the people who can’t quit smoking by vaping. Peter Hajek came up with a great analogy:

“Here is an analogy: Imagine you recruit people who absolutely cannot play piano. There will be some among them who had one piano lesson in the past. People who acquired any skills at all are not in the sample, only those that were hopeless at it are included. You compare musical ability in those who did and those who did not take a lesson, find a difference, and report that taking piano lessons harms your musical ability. The reason for your finding is that all those whose skills improved due to the lessons are not in the sample, but it would not necessarily be obvious to readers.”

Clive Bates also tore the meta-analysis to pieces in a blog post that’s well worth reading if you want more information, but the short version is that when it comes to meta-analyses, the phrase “junk in; junk out” is important. If the studies you’re analyzing suck, your result will suck too.

The New Study – How Do Smokers Who Vape Compare to Smokers Who Use NRT?

The new study uses data from the Smoking Toolkit Study, which is an ongoing monthly survey of over-16s in the UK, looking at smoking behaviors and things related to quitting. They use a new sample each month, but from April 2015, they’ve been trying to get people who’ve completed one survey to do a follow-up a year later. This study, then, uses people recruited from that date who also completed the follow-up survey to get an idea of how dual users’ behavior changes over time.

So they recruited anyone who reported occasional or daily smoking at the first survey, completed all of the questions about vaping and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT, i.e. patches and gums), who gave all of the extra information about possible covariates (things like strength of urges to smoke and motivation to quit) and then completed the follow-up survey a year later. By the end, they had a sample of around 1,500 adults, with 292 smokers who also vaped, 117 smokers who also used NRT and the rest being exclusive smokers.

The idea was simple: to see if “dual use” of vaping or NRT had any impact on the likelihood of quitting or attempting to quit, and in particular, to find out if the results of the meta-analysis stand up to scrutiny.

5 Key Takeaways From the Study

1 – Smokers Who Vape are Just as Likely to Try to Quit (Maybe Even More Likely)

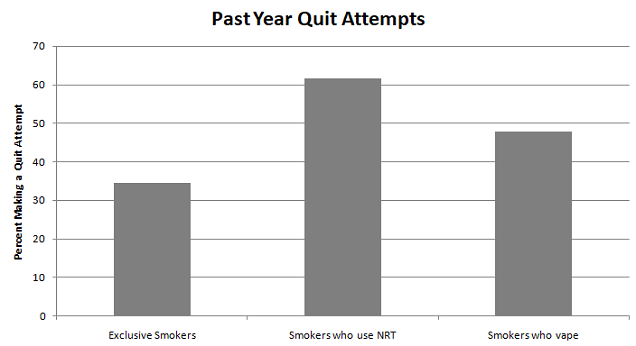

When the researchers compared smokers who also used vaping products or NRT at the time of the first survey with those who had only smoked, there was no difference in the number of quit attempts. Before the researchers adjusted for other important factors, dual users of cigarettes and NRT were the most likely to quit, followed by the dual users with vaping products and finally, those who only smoked. In particular, this means that if somebody both smokes and vapes in real life, they’re more likely to try to quit than the average smoker.

The adjustment is important, though, and the results that take everything into account show that it isn’t vaping or NRT itself that’s encouraging the quit attempts, but that people who are more likely to try to quit are trying vaping and NRT. However, even with this in mind, the results clearly show that fears of vaping simply reinforcing nicotine addiction probably aren’t valid.

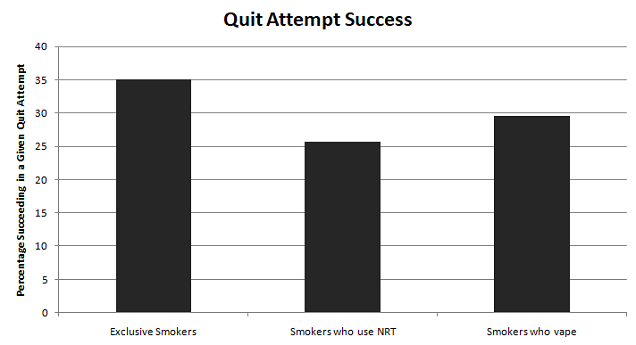

2 – Smokers Who Vape Aren’t Less Likely to Succeed in a Quit Attempt

The major claim from the Stanton Glantz meta-analysis is that people who use both vaping products and cigarettes are less likely to successfully quit than people who just smoke. The previous point shows they’re just as likely to try to quit, but the study also found no difference in success rates for smokers who vape or also use NRT, compared to those who just smoke. The authors point out that the data wasn’t sensitive enough to completely rule out the possibility of a lower quit rate, but they found no evidence it was the case.

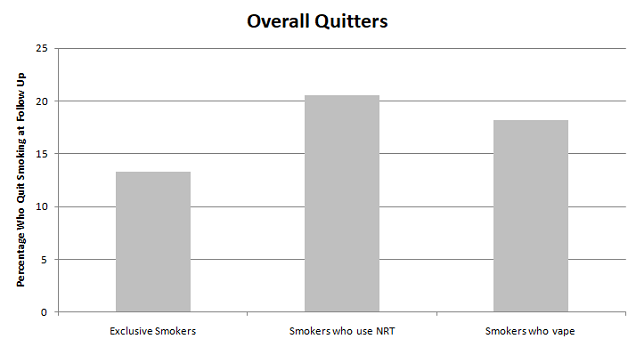

3 – Overall, Smokers Who Vape Were No Less Likely to Quit Within a Year

Smokers who also vaped at the start of the study were more likely to have quit by the end of the study overall, compared to exclusive smokers. However, this was only significant before the adjustments were made for covariates. Of course, these adjustments are important; they mainly serve to separate out other factors influencing the result. It isn’t that vaping itself increases the chance of quitting based on this data, but the unadjusted result shows that dual users in the real world are more likely to quit than people who just smoke, even if the actual cause of the increased chances isn’t related to vaping.

However, the adjusted results tackle some of the key points from the original meta-analysis too, notably finding that smokers who vape didn’t have less chance of quitting than smokers who didn’t vape. The study actually shows increased chances of quitting, but after the adjustments the difference wasn’t statistically significant. Additionally, there was no difference in overall quitting between smokers who vaped and those who used NRT, although the study didn’t have enough statistical power to rule out a reduced chance of quitting for the vapers.

4 – Smokers Who Tried Vaping During the Study Usually Tried to Quit

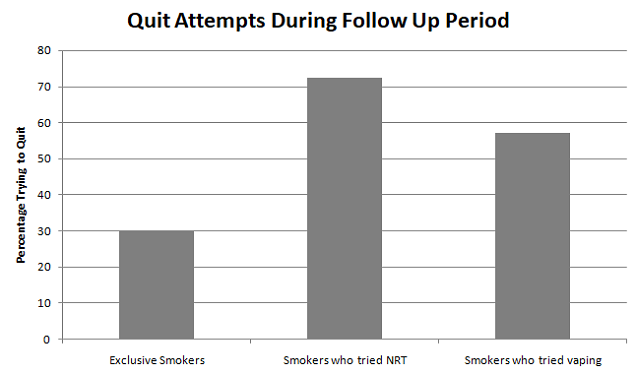

The rest of the study focused on people who were just smokers at the start of the study, but took up vaping or NRT in the year between the original survey and the follow-up. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the smokers who tried either vaping or NRT were more likely than smokers who didn’t to make a quit attempt in the next year. For smokers who vaped, 57 percent made a quit attempt, while for those who used NRT, about 72 percent made a quit attempt, compared to 30 percent of those who tried neither. The adjusted comparison shows that smokers who tried vaping were 2.8-times more likely to make a quit attempt than smokers who didn’t try vaping, although they were probably less likely to try to quit than smokers who used NRT (the difference wasn’t significant, but vapers odds of quitting were much lower).

5 – Overall Quit Rates Were Higher for Smokers Who Tried Vaping During the Study

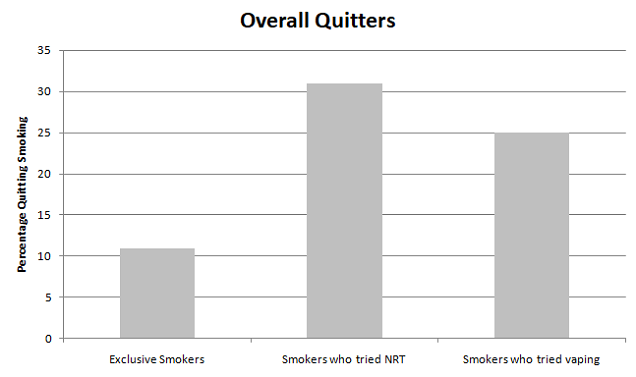

The picture is very similar when you look at the overall quit rates among exclusive smokers who tried vaping or NRT during the study compared to those who tried neither. Overall, 11 percent of smokers who used neither quit in the year, compared to 25 percent of those who tried vaping and 31 percent of those who tried NRT. The adjusted results show that overall quit rates were 2.8 times higher in smokers who vaped compared to smokers who didn’t vape or use NRT during the follow-up period. There wasn’t a significant difference in the chance of quitting for those who tried vaping and those who tried NRT, but it’s possible that the study just didn’t have a big enough sample to detect a difference.

Dual Use: Facts vs. Fear

The results of this study admittedly don’t jump out as a major win for vaping, but it’s important to remember that we’re talking about a different group than usual. Dual users, by definition, didn’t completely stop smoking when they took up vaping, and so you’d assume they’d be the more addicted smokers on that basis alone. The authors point out in the paper that dual users of cigarettes and vaping products tend to smoke more, suggesting that they’re more addicted, and people with stronger addictions understandably find it more difficult to quit.

So it isn’t really surprising that the smokers who vape in this study weren’t more likely to quit than the exclusive smokers. In contrast, though, the smokers who tried vaping during the course of the study were more likely to quit than the smokers who didn’t try vaping. This is because they didn’t get stuck at the dual user phase, this sample actually includes the people who transition to just vaping after trying it, rather than only the ones who couldn’t take this step at first. In a nutshell, this study considers dual users specifically, and the closest thing to looking at vaping’s usefulness for quitting in general is the result for the people who tried vaping during the course of the study.

The real point of the research is to tackle the misleading claims about dual users made by people like Stanton Glantz. By looking at other factors that affect the chance of quitting as well as make somebody more likely to be a dual user (e.g. how addicted the individual is to smoking), and analyzing the data with that in mind, the researchers painted a more realistic picture of dual use. Overall, there are many similarities between smokers who also vape and smokers who also use NRT, and the most important thing is that it does not make it less likely that they will quit. The claim that vaping is “associated with significantly less quitting among smokers” is outright false.

At this point, we shouldn’t be surprised when anything Stanton Glantz says turns out to be false, but if you want to prove it, this study does a great job.