If there was one rule for conducting scientific studies on a topic, it would be to make sure you understand it first.

But with e-cigarettes, that is not what happens.

All too frequently, researchers publish studies on e-cigarettes that show they have no idea what they’re doing, and the result is invariably a study that ends up misleading many smokers yet to make the switch.

As vapers, we obviously know more about the technology than non-vapers, and you might think it’s a little unfair to criticize researchers who were at least trying to get things right.

But I disagree: if you’re a scientist studying a topic, doing some basic research into it before you start designing a study or taking measurements is absolutely necessary. If somebody conducted a study on a medication but got the dosing schedule wrong, they’d be the subject of ridicule. If somebody was studying the risks of smoking but did so by setting fire to the filter and testing the smoke that came out of the other end, they wouldn’t even be able to publish the results.

If you have the gall to publish something on the topic of e-cigarettes, but don’t know the first thing about it, you’re either unbelievably arrogant, absolutely clueless or both. In any case, you deserve to be severely mocked for it.

1 – “We don’t understand the settings vapers use”

The New England Journal of Medicine formaldehyde study was the main inspiration for this post. The reason it’s so misleading is widely known in vaping circles: the combination of the atomizer and the settings used would lead to dry puffs. Vapers don’t like dry puffs.

The researchers’ thought process behind the design of the study appears to have been: “let’s get an iTaste MVP kit, crank it up to the maximum voltage and see how much formaldehyde we detect.”

This is comparable to saying (as Peter Hajek suggested) “let’s put some bread in the toaster, turn it up to the top setting and see how dangerous the toast that comes out is.”

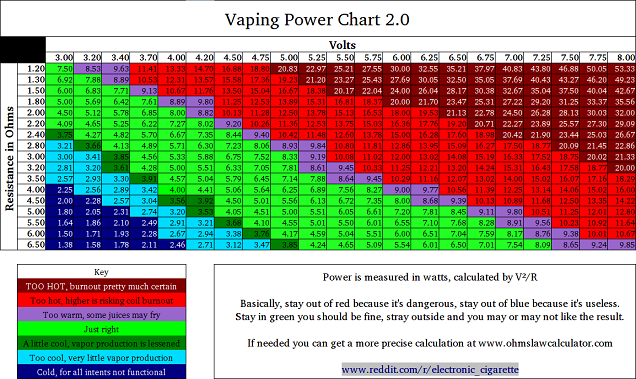

All they would have needed to do is Google “vaping power chart” or “e-cigarette settings” or really anything at all related to the issue at hand to find the answer. They’d have found something like this:

If they were really interested in finding out more, they could have asked a question on one of the many forums to determine what the appropriate setting for a CE4 clearomizer is. They could have even asked what the 5 volt setting is for. They could have asked (or even found out from other published research) what a dry puff is, and learned why people avoid it. Or, most controversially of all, they could have just tried vaping at the settings used and worked out the problem for themselves.

However, it seems they were too sure of themselves for any of that. Even when they presented with criticism of the method on exactly these grounds, they just dismissed this as “speculation,” and said that the flavorings would probably cover up the harsh taste anyway.

It’s the Dunning-Kruger effect at work: if you’re incompetent, you probably don’t even realize it, because seeing your error would require competence.

2 – “We tested dripping, but we have no idea how to do it”

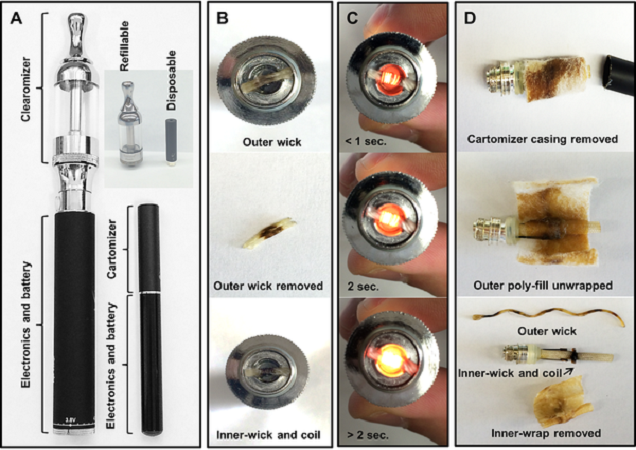

In a study looking at the effect of vapor on cultured cells and mice, the authors tested “dripping,” at least as they understand it:

An emerging trend abandons use of the clearomizer and replaces it for an inhalation tip that does not hold e-fluid. The “drip tip” allow consumers to “drip” e-liquid directly onto the heating element wick.

Err… yeah. While not too horrendously incorrect, the strained description and questionable understanding of what a drip tip is (and is used for) indicates that they’re probably out of their depth here.

The picture they showed reveals their biggest error:

You see, where most dripping takes place on dripping atomizers (who’d have thunk it?), they apparently just thought exposing the coil on a clearomizer and dripping “small amounts of e-liquid sufficient to absorb into the wick” was how it was done. Rip Trippers eat your heart out.

So here’s a group of researchers that somehow correctly identified that some vapers drip, but miraculously managed to remain completely ignorant of the devices they use for dripping and how much e-liquid is applied to the wick.

Again, Googling “e-cigarette dripping” or just asking a vaper would have led them in the right direction (they could have even spent $30 and bought an RDA to test), but these intrepid researchers just ploughed on regardless, allowing their total lack of understanding of what they were doing to guide them.

3 – “If it produces vapor, the cartridge must still be OK”

In a study where mice were confined in a two liter container and basically poisoned with nicotine for a couple of weeks, the researchers decided to forget all about “manufacturers’ recommendations” and “common sense” (because who needs that, right?) and push the cartridges they used well beyond breaking point.

The method section explains that they used NJOY devices (all cigalikes) and exposed the animals for three hours a day, with each individual device being puffed once a minute. Three hours is 180 minutes, so that’s 180 puffs per e-cig per day. However, although they said this was highly variable, they explained that “e-cig cartridges were replaced each week.” Assuming this is the average time until the cartridge was replaced, that’s 1,260 puffs per cartridge.

A cartridge only holds about 1 ml of e-liquid, so the idea it can be used for over 1,000 puffs is frankly ridiculous. Although they’ve since removed the precise recommendation, NJOY’s website at the time (viewable thanks to the Wayback Machine) clearly stated that their disposables (with roughly the same size cartridges) were good for about 180 puffs. This is just one day of use under their puffing schedule.

Did the researchers not check out the recommendations? Did they not consider that the wicking material could burn and still produce some “vapor” (i.e. smoke from burning wick) that may fool a smoking machine?

As usual, we can only assume that the researchers were so confident in what they were doing that they didn’t bother to check. I’m expecting them to follow-up with a study looking at what happens to mice exposed to the smoke produced from burning a cigarette and then the whole filter sometime soon.

4 – “People vape concentrated flavorings, right?”

There are so many e-juice flavors on the market, so how can a lowly researcher be sure he or she is genuinely testing the sort of thing people vape?

Well, it’d be a good start to make sure you weren’t testing a concentrated flavoring and treating it as if it’s a ready-to-vape juice.

You may be under the impression that no researchers would do something so monumentally silly, but you’d be wrong. A study that spread concern about cinnamon flavorings listed the liquids they tested, and Dr. Konstantinos Farsalinos went to investigate. He found that four of the eight cinnamon e-liquids they tested were actually concentrated flavorings.

I hope none of the authors decided to switch to vaping: they’d get some seriously intense flavor, but they’d probably find the nicotine content a bit lacking.

5 – “No need for better wicking; you can vape pure VG on a crappy clearomizer”

Consider the results of this study on the toxicity of e-cig vapor to cells: while vapor was much less toxic than cigarette smoke, VG alone was more toxic than a complete e-liquid. How could that be? Is it that some other ingredients in e-liquid magically protect the cells against the “damage” caused by VG? Or, maybe, is it that the researchers had no idea what they were doing?

As Dr. Farsalinos pointed out in his talk at the Global Forum on Nicotine, the researchers didn’t seem to realize that you might run into some problems if you try to vape pure VG on a crappy clearomizer. As every vaper who has vaped high-VG juice knows, the viscosity is a big problem for wicking. VG is thick, and you need a device with excellent wicking to cope with the thicker juice.

That’s why pure VG liquid is very rare, and is usually diluted with water or a small amount of PG to make it a little thinner. Combine this with the short interval the researchers used between puffs (despite actually pointing out themselves in the discussion section that they didn’t use a realistic protocol), and you’ve got a recipe for dry puffs. And as discovered by other intrepid, vaping-ignorant researchers, this can lead to harmful breakdown products in the vapor.

If only there was some compendium of information the researchers could have accessed from a smartphone, tablet or computer to see if there would be any problems with vaping pure VG. If only there was some sort of “search engine” they could have used to search it for information about using pure VG in an e-cigarette. If only there were forums and forums full of people willing to advise them on problems they might run into.

But no, who needs the internet, Google and the E-Cigarette Forum? You can just push on regardless, hiding your lack of knowledge behind your misplaced confidence that you know what you’re doing.

Researchers: Ask Before You Do Something Dumb

The message behind this post is very simple. If you don’t understand something, or if you’re not quite sure that what you’re doing is appropriate, it’s no use to just push on and hope everything will be OK. This is doubly true if you happen to be trying to study something that’s relevant to people in the real world, and if your findings – like those of the NEJM formaldehyde study – might even lead to people returning to smoking instead of continuing to vape.

The big problem, though, is the lack of engagement with the vaping community from researchers. As I’ve pointed out numerous times in this post, there are forums and forums full of people willing to answer questions about vaping, whether from new vapers or researchers unsure of how best to proceed. Vapers are helpful, and want reliable scientific studies to be conducted on e-cigarettes. Hell, you could probably even find a vaper to come down and test out your puffing protocol for you directly and offer feedback. All you have to do is reach out and ask.

If those in the research community continue to conduct studies without bothering to even learn about the thing they’re studying, then the formaldehyde scare in the wake of the NEJM formaldehyde study won’t be the last. And, if we’re really unlucky, more vapers will decide they “might as well smoke” as a result.