It isn’t news that people vastly overstate the risks of vaping. Pretty much every study on the topic has shown that shocking numbers of people – in the US, the UK and elsewhere – believe vaping is as dangerous as or even worse than cigarette smoking when it comes to your health. And, despite evidence continually mounting that vaping is much safer than smoking, public perceptions of the risks are still moving in the wrong direction.

Vaping advocates argue that this misunderstanding prevents people switching to vaping and discourages them from continuing after switching, but up until now this has been more of an assumption, with only pretty limited scientific evidence to back it up. However, a new study has confirmed these fears, showing that dual users who know vaping is safer than smoking are more likely to quit smoking and less likely to revert to smoking.

In fact, the study shows that 205,000 more would have quit smoking completely in 2016 if they’d understood that vaping is much safer. In a nutshell, the study shows just how dangerous misinformation is.

The Problem: Vaping is Safer than Smoking, But People Don’t Know It

The problems in the vaping debate are clearly encapsulated by statistics on public understanding of the risks of vaping vs. those of smoking. The science is unambiguous on this point: vaping is much safer than smoking. Every serious analysis of the evidence has reached this conclusion, from the UK Royal College of Physicians to the US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine.

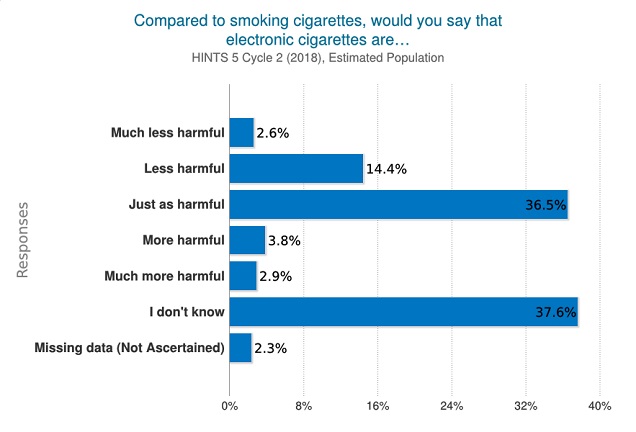

However, studies looking at the public’s understanding of this fact – and it is a fact – consistently paint a picture of confusion and misunderstanding. For example, in 2017, only 34 percent of US adult smokers knew that vaping was safer than smoking, down from 45 percent in 2012. A different survey from 2018 showed that only 17 percent of the US public overall knew that vaping was safer than smoking.

Given that being safer than smoking is the primary benefit of vaping, it doesn’t take much of a leap of logic to assume this will have negative effects and fewer people will switch to vaping as a result. If that is the case, spreading misinformation on the topic is immoral to say the least.

As argued by Lynn Kozlowski and Dave Sweanor in their paper on the ethics of withholding information about the varying risks of tobacco and nicotine products:

If science learned that one type of alcoholic beverage caused 3 in 5 regular users to die prematurely, losing 10 years of life, while another alcoholic beverage caused 95% or even 9.5% fewer premature deaths, consumers would want to know which legal product was which. […] It would be scandalous, even criminal, to keep such facts from consumers. Yet, such facts are being kept from adult consumers of legal tobacco/nicotine products either by not informing or actively misinforming consumers. It is as if tobacco consumers were blindfolded and not allowed to see dramatic differences in harm from different products.

The New Study: Do Opinions on Vaping's Safety Impact the Chance of Switching?

The researchers on the new study wanted to see if this potential problem really is coming through in the numbers of people switching to vaping, in particular looking at dual users and how their views of the risks of vaping affected their outcomes a year later. They used data from the second and third waves of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study to look at this.

The researchers used data from 2,211 adults with data at both waves (which ran from October to October, 2014/15 and 2015/16) who used both e-cigarettes and cigarettes in the month before the initial survey (i.e. “dual users”). As well as their perceptions of the risks of vaping and smoking, and their smoking and vaping statuses, the researchers also gathered some information about how often they vaped and smoked at both time-points.

What They Found: People Who Think Vaping is Safer are More Likely to Switch

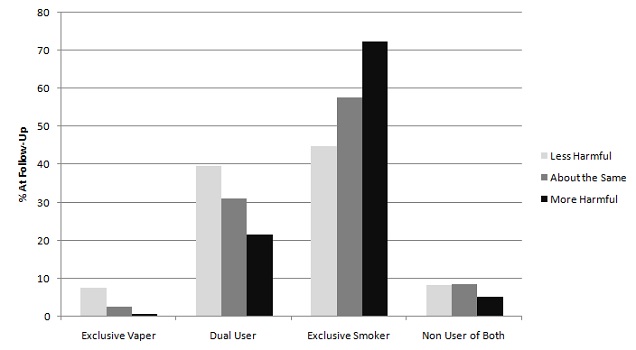

The headline finding of the study is that the dual users who knew that vaping was safer than smoking were more likely to have quit smoking and exclusively vape a year later. The raw data shows that 7.5 percent of dual users who said vaping was safer had quit smoking a year later, compared to 2.7 percent of people who though the risks were the same and 0.7 percent of people who thought vaping was more dangerous. Overall, the researchers calculated a near three-fold increase in the chance of quitting smoking for those who thought vaping was safer vs. other dual users.

Conversely, they were also significantly less likely to have stopped vaping and reverted to smoking, with around 45 percent reverting to smoking, vs. 58 percent for people who thought the risks were equal and 72 percent for those who thought vaping was more dangerous. They were 50 percent more likely to remain dual users of both products, but there was no difference in the groups’ chances of stopping both vaping and smoking.

When the researchers looked at people who said vaping was safer than smoking at both waves of the survey, the differences were even more marked. For example, 11.3 percent of these dual users had switched to vaping exclusively at the second survey, compared to 1.1 percent of those who consistently said vaping was as bad as or worse than smoking.

The differences when the researchers looked at the frequency of smoking and vaping from the start to the end of the study weren’t as pronounced or clear-cut. For example, dual users who said vaping was safer tended to smoke on fewer days, but only 2.5 fewer per month, and similarly, fewer cigarettes per day but only around two fewer (and this wasn’t a statistically significant result).

Finally, the participants who didn’t think vaping was safer than smoking at first but did by the second survey reduced the number of days they smoked by an average of two days by the second survey. The people who went in the other direction didn’t show any significant changes.

How Many Lives Could Accurate Information Save?

The most interesting part of the discussion section for the paper tries to put some population-level numbers on the results and estimate the difference that could be made by correcting risk perceptions.

For example, there were about 10.5 million dual users in the 2014-15 wave of the survey, and about 4.3 million didn’t think vaping was safer than smoking. Of these, only 115,000 quit smoking by the follow-up survey. However, if their quitting rate was the same as those who thought vaping was safer, an extra 205,000 would have quit smoking over that period. If they had the quitting rate of those who said vaping was safer at both time-points, an extra 370,000 would have quit smoking.

When you remember that the risk perceptions are moving in the wrong direction, these figures really take on the proper context. The authors point out that dual users are probably more likely to act on relative harm information, because they’re willing to both vape and smoke. If they shift further towards inaccurate perceptions of the relative risk, even fewer will completely switch to vaping. Conversely, if harm perceptions moved in the right direction, we would see the gains calculated in this study, of literally hundreds of thousands of extra quitters.

While the study doesn’t address the impacts on smokers trying vaping in the first place, it isn’t much of a leap to assume the same factors are at play. Concerns about the risks of vaping seem to be one of the most important factors in smokers not trying it out based on UK data, and if this study had included smokers who hadn’t tried vaping at the time of the first survey, it’s hard to imagine the results being much different. Their calculation suggests that misinformation is leading to at least 205,000 fewer quitters, but in reality the number is probably much higher.

When Risks are Exaggerated, Smokers Suffer

In short, this study confirms what vapers have been saying for years. Misinformation of vaping is a very dangerous game, and it’s very likely that it literally costs (or at least will cost) lives.

Of course, smoking is ultimately the thing putting these smokers’ lives at risk, but that isn’t a good enough justification for distorting or withholding important information from them. Even if you don’t like vaping, any pragmatic approach to the issue of smoking-related deaths must account for the positive impact vaping can have and take steps to maximize it. If you give people accurate information, this study shows that they’re more likely to make the right choice. So why the hell wouldn’t you want to do that?