A new piece of research from Dr. Konstantinos Farsalinos and his colleagues has provided some insight into the effectiveness of cig-a-like devices compared to e-cigarette mods when it comes to nicotine delivery. This could easily be considered the most important element of e-cig performance, because that’s why we all use them in the first place, and it’s reasonable to assume they'll be more effective at helping people substitute smoking if they deliver similar quantities of nicotine.

In addition, the clinical trials conducted to date on e-cigarettes have used first generation (cig-a-like) devices, so while these may be around as effective as nicotine replacement therapy for helping smokers quit, it could well be that newer devices are significantly better.

This study provides some extremely useful information on this point: newer, more powerful devices are much more effective than smaller, cigarette-like first-generation devices. It was published in Nature: Scientific Reports and is available in full for free.

Summary

- 23 participants were randomly assigned to vape the same 18 mg/ml e-liquid from a first-generation (V2 Cigs) device on one day and from a newer-generation (eVic) device on a different day, having abstained from nicotine consumption for 8 hours prior to each study period.

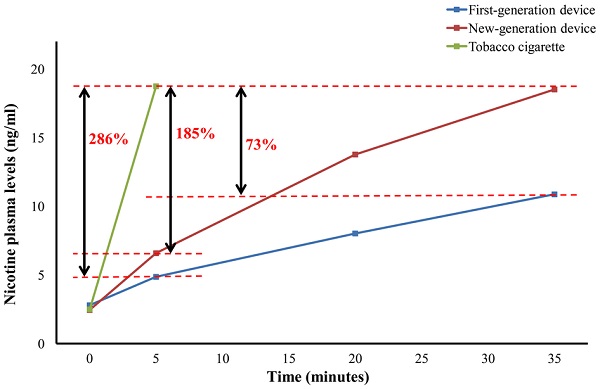

- Their blood nicotine levels were measured after 10 puffs were taken over the course of 5 minutes, and then every 15 minutes over an hour-long, ad lib vaping period. The results between devices were compared, and findings were also compared to nicotine absorption following five minutes of smoking a cigarette (as measured in other research).

- Newer-generation devices (which provide more power to the atomizer) lead to higher blood nicotine levels than first-generation devices, with the difference being greatest after 20 minutes (where newer-generation devices led to 70 percent higher nicotine absorption) and decreasingly slightly afterwards.

- Users’ cravings were less intense after using the newer device, and they rated it as more satisfying. The first generation device was rated as looking and feeling more like a cigarette.

- Compared to smoking a cigarette in five minutes, both devices provided much less nicotine to users’ bloodstream. The first-generation device led to four times less nicotine in the blood than a cigarette after five minutes, and the newer-generation device led to three times lower levels.

- After 35 minutes, mod users achieved similar blood nicotine concentration to that obtained after five minutes of smoking, but the first-generation device didn’t accomplish this even after 65 minutes.

- The researchers conclude that liquids of around 50 mg/ml would be needed to match nicotine delivery from a cigarette, and point out that limiting e-liquid to 20 mg/ml of nicotine would lead to inefficient doses of nicotine for users.

What They Did – Measuring Plasma Nicotine Levels After Vaping

The researchers recruited 23 participants who were all ex-smokers and had been vaping for at least one month. They had previously been heavy smokers (an average of over 30 cigarettes per day), and had been vaping for an average of 19 months, although 20 of them had quit smoking within a month of starting to vape. Just over half had tried and failed to quit smoking before they tried vaping, and were all less dependent on vaping compared to how dependent they were when smoking, according to two different tests for cigarette dependence.

The basic aim of the study was to measure their blood nicotine levels after they used two different devices, a V2 Cig (fully charged) with cartomizer and an eVic with EVOD (set to 9 watts), with each participant testing each device on different days. In each case, the liquid tested was an 18 mg/ml option from Flavourart (they conducted a chemical analysis on the liquid too, finding any harmful components in only trace amounts and the nicotine level just 0.3 lower than the stated 18 mg/ml). Prior to each test, participants abstained from vaping, caffeine, food and alcohol for eight hours, so baseline measurements of plasma nicotine could be taken before each session. In each session, participants took ten puffs on the e-cig in five minutes, which was designed to replicate smoking a cigarette, and then blood samples were taken for analysis. After this period, there was a 60 minute “ad lib” period of vaping, in which users could vape as much or as little as they chose to and a blood sample was taken every 15 minutes.

Although the blood nicotine levels were the main focus of the research, they also were assessed using the Craving Withdrawal Scale questionnaire to see what affect each e-cig had on users’ nicotine cravings, and they were also asked questions relating to how satisfied they were. Carbon monoxide breath levels were also taken, and the nicotine absorption following vaping was compared with that obtained from a tobacco cigarette in other research.

What They Found – New Devices Are Better, But Still Don’t Offer Enough Nicotine

Baseline plasma nicotine levels were similar between devices, but in every subsequent measurement they were significantly higher when participants used the newer device. After five minutes, first generation device users’ plasma nicotine levels rose from 2.80 ng/ml (nanograms –billionths of a gram – per milliliter) to 4.87 ng/ml, and after the same time period the newer-generation device users’ levels increased from 2.46 ng/ml to 6.59 ng/ml. The difference between the two devices was most notable after 20 minutes (after the 5 minute, 10 puff session and 15 minutes of ad lib use), where the newer generation device provided 70 percent higher plasma nicotine levels than the first generation one, but this reduced to 49 percent higher after 65 minutes. At this point (the end of the test period), the first generation device users had blood nicotine levels of 15.75 ng/ml and those using the higher-powered device had levels of 23.47 ng/ml. As would be expected, there was no significant change in exhaled carbon monoxide levels by the end of the test period with either device.

The difference in cravings between devices indicates that along with providing more nicotine, newer devices are more effective at reducing cravings (as would be expected). On the Cigarette Withdrawal Scale, there was no significant difference between groups at the baseline (before vaping) and after five minutes, but users of the newer devices had a significantly lower score after 65 minutes of use. Another simpler measure of craving (where users placed a mark on a 1 to 100 scale indicating their level of craving) obtained similar results, but this found a statistically significant difference between the different devices after five minutes too, although both significantly reduced cravings compared to the baseline level. Additionally, users rated the V2 Cig as feeling and looking like a tobacco cigarette, but the eVic as more satisfying and producing a stronger throat hit.

Although the comparison between the two devices is interesting, the most important thing for smokers looking to make the switch is how the nicotine delivery of an e-cigarette compares with a tobacco cigarette. An older study of e-cig nicotine absorption was used as a source of information regarding nicotine absorption from smoking, and it found that smoking a single tobacco cigarette in five minutes led to an increase in plasma nicotine from 2.1 ng/ml to 18.8 ng/ml. If you only take the initial five minutes of e-cig use (so the puff-count and time frame are equal), e-cigs provide much less nicotine than a cigarette – three times less in the mod and four times less in the cig-a-like device. After 35 minutes (with an additional half an hour of ad lib vaping), users of the mod were able to achieve nicotine levels similar to five minutes of smoking a cigarette, but the cig-a-like device provided 73 percent lower plasma nicotine levels after this time period. Even after 65 minutes, the cig-a-like users had 19 percent lower nicotine levels than would be obtained from five minutes of smoking.

Why Do E-Cigarettes Provide Less Nicotine?

In the discussion section, the researchers speculate as to why even the more efficient e-cigarettes provide less nicotine than a tobacco cigarette. In a previous study, the researchers determined that 18 mg/ml would roughly be strong enough for vapers to consume 1 mg of nicotine in five minutes, which is equal to the amount consumed by smokers in the same time period (however, the method used to determine this for cigarettes is known to underestimate delivery). Despite this, it’s clear that this doesn’t translate to equal blood nicotine levels, suggesting that the body doesn’t take on nicotine delivered by e-cigs in the same proportion.

In the discussion section, the researchers speculate as to why even the more efficient e-cigarettes provide less nicotine than a tobacco cigarette. In a previous study, the researchers determined that 18 mg/ml would roughly be strong enough for vapers to consume 1 mg of nicotine in five minutes, which is equal to the amount consumed by smokers in the same time period (however, the method used to determine this for cigarettes is known to underestimate delivery). Despite this, it’s clear that this doesn’t translate to equal blood nicotine levels, suggesting that the body doesn’t take on nicotine delivered by e-cigs in the same proportion.

The researchers suggest that nicotine from e-cigs might be absorbed by the inside of the mouth (the oral mucosa) rather than the lungs, leading to absorption rates similar to patches and gums. If this is the case, some of the ingested liquid would also be swallowed, which would further limit the amount available to increase blood-nicotine levels. Alternatively, they suggest that the combination with PG and VG in e-liquid may adversely affect the lungs’ ability to absorb nicotine. In either case, this is an interesting issue and one which the researchers suggest further work on. However, as things stand, the researchers suggest that liquids in 50 mg/ml concentration would be needed to provide similar nicotine delivery to a tobacco cigarette.

What Does This Mean for Regulation and Smoking Cessation?

The implications for being able to successfully quit smoking using e-cigs are immediately obvious. It doesn’t take much of a logical step to assume that to replace smoking as a means for nicotine consumption, the closer the nicotine absorption approaches that from a cigarette the better. So, the fact that both clinical trials conducted thus far on e-cigarettes’ effectiveness for quitting smoking used first-generation devices means that trials on newer devices will probably show that e-cigs are even more effective for helping people quit smoking than we previously thought.

For regulators, this should be a lesson that suggested nicotine limits – like the European Commission’s now-approved 20 mg/ml limit – are illogical and potentially counter-productive. With the suggestion that a concentration of around 50 mg/ml would be needed to adequately provide a cigarette-like dose of nicotine, this will severely limit the effectiveness e-cigarettes and likely lead to some smokers continuing to do so when they would have otherwise been able to get their fix through vaping.

This research was presented (in part) to the FDA at a hearing by Dr. Farsalinos, and we can only hope they paid attention and will avoid imposing a similarly senseless limit on nicotine. In short, for e-cigarettes as a technology, the amount of nicotine provided is integral to their success. This research suggests that anybody trying to quit smoking would likely be better off with a more powerful device, and that, if anything, we should be looking for ways to make e-cig pens more addictive than they currently are.