To say that vaping has been controversial would be a massive understatement. Ever since they hit the market, anti-smoking groups and many others have been touting over-exaggerated risks and downplaying some fairly obvious benefits. Along with things like the formaldehyde scare and overblown concerns about vaping serving as a gateway to smoking, you see a surprising number of people claiming that vaping actually doesn’t help smokers quit, or even that it actually makes it harder to quit.

Some of the most well-known groups and people to make this claim include the World Health Organization and Stanton Glantz, whose meta-analysis of quitting studies forms the basis of most claims that vaping actually reduces quitting rates.

If these claims were true, it would be quite devastating to the potential of vaping to improve the health of the population. No matter how much vaping reduces risks compared to smoking – which is generally considered to be by at least 95 percent – if it actually reduced quitting rates or didn’t improve them compared to cold turkey quitting or something like nicotine replacement therapy (NRT – like patches or gums), then it wouldn’t be much use. In fact, it would arguably even be harmful.

The good news is that these claims are categorically false, and a few recent studies underline that point very nicely. So here’s detailed a run-down of why we know vaping helps smokers quit.

The Evidence Vaping Helps Smokers Quit

There is one thing to head off straight away: there aren’t tons of randomized controlled trials for us to work from. There isn’t some huge store of multi-year trials to combine into a robust systematic review or meta-analysis that will answer the question once and for all. If you want to be a complete scientific purist about it, you could choose to hold out for more evidence before coming down on the issue one way or another.

But before you jump to this ivory-tower, “more-scientific-than-thou” position, remember that basing your opinion solely on rigorous evidence isn’t without problems. This is beautifully illustrated by the paper “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” This was unable to find any randomized controlled trials on the subject, and so concluded:

As with many interventions intended to prevent ill health, the effectiveness of parachutes has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation by using randomised controlled trials. Advocates of evidence based medicine have criticised the adoption of interventions evaluated by using only observational data. We think that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence based medicine organised and participated in a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.

This ingenious spoof takes the objection to the extreme, and of course, the idea that vaping helps smokers quit isn’t quite “parachutes work” levels of obvious, but there is a solid point at the core of the paper. If you refused to use a parachute on the basis that there have been no clinical trials, or especially if you said we couldn’t claim that jumping with a parachute was better than jumping without one, you’d immediately become a laughing stock.

Because reality matters. You can use your brain and evaluate the effectiveness of something even without clinical trials if you actually want to. It might not be perfect but there isn't just one way to find things out. So, keeping that in mind, let’s look at some of the “not a clinical trial” evidence that scientific purists would have us completely ignore when trying to answer the question of whether vaping helps smokers quit.

Anecdotes

Anecdotes are the worst form of evidence there is, but they are still evidence in some form. I can anecdotally tell you that I know people who’ve skydived with a parachute and survived, and you would be completely within your rights to say you want more assurance than that before entrusting your life to one. The problem is that anecdotes only tend to tell one side of the story. You hear about all the times parachutes worked but much less about the times they didn’t (because only one group is around to tell their story).

But if you had thousands of people all telling you that parachutes worked for them, would you really be as skeptical? The Consumer Advocates for Smoke-Free Alternatives Association (CASAA) has a huge collection of testimonials, totaling around 11,710 at present, and this is only a small sample of the number of real-world stories floating around the internet.

Of course, it’s entirely possible – and in fact probable – that there are even more stories going untold about how vaping didn’t work for people. But with this much support, at very least the idea warrants further investigation. So let’s dig a little deeper.

The Rationale Behind Vaping

We know parachutes will work even without a clinical trial because we understand the underlying physics. Even it was the first time you’d ever seen or heard of a parachute, if you understood the basics of classical mechanics and air resistance, you could be pretty confident that it should work. In the same way, we have a good understanding of the rationale behind vaping.

Often, the very same organizations that cast doubt on the effectiveness of vaping for quitting smoking happily promote NRT. These products, including patches, gums and inhalers, work on the basis that providing smokers with an alternative source of nicotine will help them quit smoking. And the evidence suggests that this assumption is true, and NRT does help smokers quit (compared to cold turkey quitting). Similarly, evidence from Scandinavia strongly suggests that smokeless tobacco helps people stop smoking for the same reason.

So – if we’re going to be ever-so-slightly bold about it – it looks a lot like alternative sources of nicotine are generally effective for helping smokers quit. Vaping is an alternative source of nicotine, and one that successfully provides nicotine to users (albeit, like NRT, less effectively than a cigarette) so it’s pretty reasonable to suspect that they would also be effective as quitting aids. With this simple point in mind, it would be weirder if they didn’t help than if they did. If people find it easier to quit with something like a patch on their arm or a teabag full of snuff on the inside of their lip, why would they struggle to do the same with something that works a lot more like a cigarette?

The Decline of Smoking Rates

Alongside anecdotes and the underlying rationale behind vaping being an effective substitute for smoking, there is more indirect evidence in the form of declining smoking rates as vaping becomes more common.

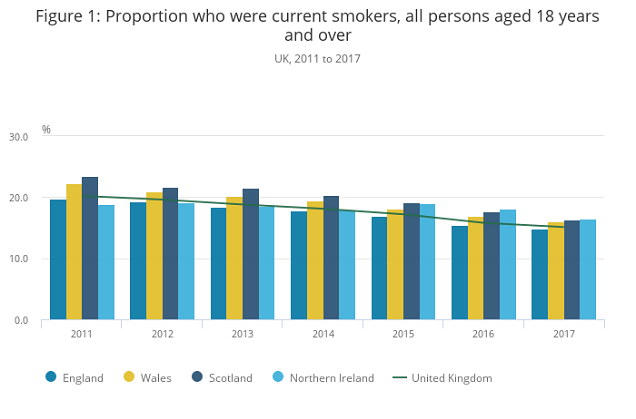

In the UK, about 20 percent of adults smoked in 2011, but this declined to 15 percent in 2017 alongside the rise in vaping. Public Health England estimates that there are about 6.1 million smokers in the England, with about 2.5 million vapers, 1.2 million of whom have quit smoking. Researchers have also used UK data to show a positive association between the use of e-cigarettes by smokers and success rates in quit attempts, so there is more to this than just a basic look at the population's smoking and vaping rates.

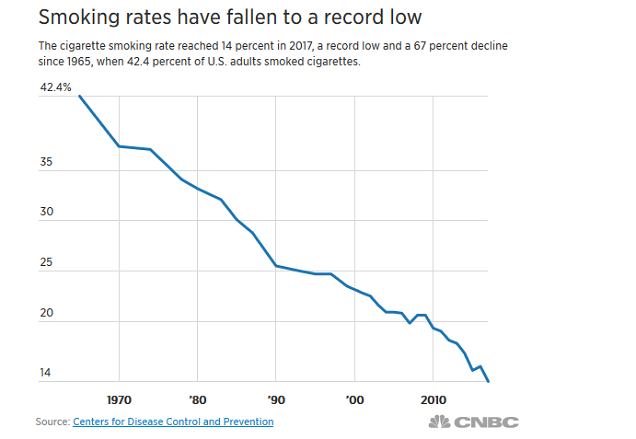

There has been a similar decline in the US, with smoking rates falling from 19 percent in 2011 to 14 percent in 2017. Comparatively, in 2001, 22.8 percent of Americans smoked, and this declined to 19.8 percent by 2007, a smaller decline than we’ve seen during the rise of vaping. Researchers have also analyzed youth smoking rates amid the rise of vaping and found this same inverse relationship: when vaping increases, smoking decreases.

Of course, smoking was declining anyway, and the scientific purists among you might point out (correctly) that this isn’t definitive proof that vaping is the cause of the decline.

But, continuing the parachute analogy, this is like seeing much fewer deaths from falling out of planes in the general population after hearing thousands of people telling you how they work and learning about the physics underlying their usefulness. Admittedly it doesn’t conclusively prove anything but it’s hard to see the statistics without suspecting that these parachute things might be useful after all.

At this point, I'd personally be feeling pretty confident about that parachute. Even without cohort studies and double-blind trials, it seems like a solid idea and the best thing to have with you if you happen to be falling out of a plane. For vaping, though, this is just a baseline. Other evidence does exist, but when you’re considering it, it’s important to keep this baseline in mind. Ignoring all of this and focusing just on the trials is a pretty common mistake when people talk about vaping's potential to help smokers quit.

Early Studies on the Effectiveness of Vaping for Quitting Smoking

Before we move onto some more robust scientific evidence of the effectiveness of vaping, it’s worth taking a minute to think about what we know already, without any clinical trials or even less rigorous scientific studies. We know that smokers say vaping works, we know that vaping should work based on existing knowledge and we know that smoking rates have been declining as vaping has become more common. This wouldn’t convince the FDA, but as a normal person weighing the evidence without the confines (rightfully) placed on regulators, the case is already pretty strong.

And it only gets stronger when you look at the evidence. The earliest studies tended to be quite basic in their design and only included small numbers of participants. For instance, one study published in 2011 was described as a “proof of concept” study and recruited 40 smokers who were unwilling to quit, giving them a cigalike e-cig and following up with them for six months. At the end of the study, 22.5 percent of participants had completely quit smoking, and an additional 32.5 percent had reduced their daily cigarette consumption by half or more. This didn’t have a control group, though, and the number of participants was very small.

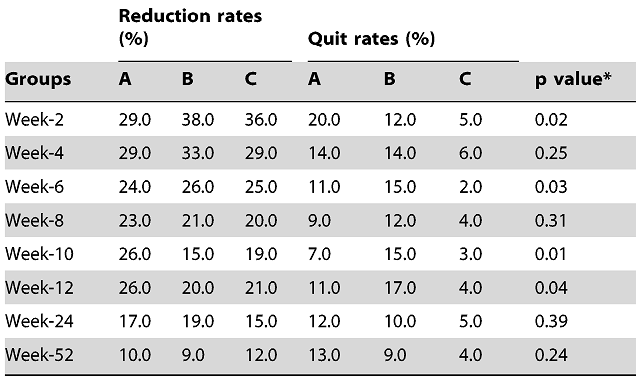

A couple of early randomized controlled trials came out in 2013. One recruited 300 smokers not intending to quit and randomized them to either receive 7.2 mg nicotine cartridges, a split between 7.2 mg for the first half and 5.4 mg for the second half, or no nicotine cartridges for the initial 12 weeks of the year-long study. The results showed that 13 percent of the 7.2 mg group, 9 percent of the mixed cartridge group and 4 percent of the nicotine-free cartridge group had quit smoking after a year.

The second is the most well-known, and recruited 657 smokers and randomized them to either receive a cigalike e-cig with 16 mg cartridges, nicotine patches or a nicotine-free e-cigarette. Six months later, 7.3 percent of the e-cig group, 5.8 percent of the patches group and 4.1 percent of the nicotine-free e-cig group had quit smoking. The difference between nicotine e-cigs and patches wasn’t statistically significant (and there is some criticism of the fact that new cartridges were received in the post, while the patch group had to go to a pharmacy for new patches), but the researchers concluded:

E-cigarettes, with or without nicotine, were modestly effective at helping smokers to quit, with similar achievement of abstinence as with nicotine patches, and few adverse events.

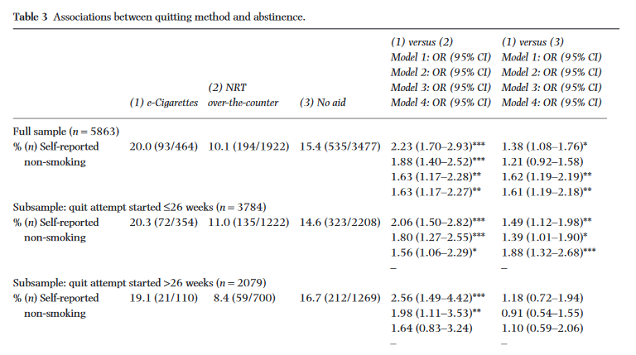

A 2014 study looked at the “real-world effectiveness” of vaping vs. NRT and quitting unassisted, based on data from 5,863 smokers who tried to quit using one of these methods. This is a cross-sectional study, so it didn’t follow smokers over time, but rather asked about their quit attempts at a single point in time, as part of the Smoking Toolkit Study.

The results showed that smokers who tried to quit by vaping were 63 percent more likely to be successful than people using NRT and 61 percent more likely than people using no aid. These smokers chose their own quit method, of course, which reflects real-world use more closely than an NRT but also opens the door for potential biases (for example, maybe people who choose to vape are more determined to quit by any means necessary than people who chose NRT or no aid).

There are a fair few other studies that could be included in this section, but the Cochrane Review on e-cigarettes for quitting smoking analyzed them all and concluded:

There is evidence from two trials that ECs [e-cigarettes] help smokers to stop smoking in the long term compared with placebo ECs. However, the small number of trials, low event rates and wide confidence intervals around the estimates mean that our confidence in the result is rated ‘low' by GRADE standards. The lack of difference between the effect of ECs compared with nicotine patches found in one trial is uncertain for similar reasons.

The most up-to-date version of this study includes 21 cohort studies and the two randomized controlled trials. The overall conclusion is a fair analysis of this early evidence: it looks like e-cigarettes help smokers quit from the scientific evidence, but more of it would be needed to produce a firm recommendation and draw a clear conclusion.

The Claims That Vaping Doesn’t Help Quitting: Why the Evidence Doesn’t Stack Up

So now we have anecdotes, a very plausible rationale, falling smoking rates and some tentatively positive results from scientific studies into vaping for quitting smoking. At this point you might be wondering: why exactly do people bother claiming that vaping doesn’t help smokers quit?

Stanton Glantz’s meta-analysis is the best place to look for an explanation. The study collects data from 20 studies and combines them to produce a single result, and this includes 15 cohort studies, three cross-sectional studies (which only cover a single point in time) and two clinical trials, along with some others discussed solely in the systematic review portion of the paper.

The authors’ conclusion is that the odds of quitting smoking were 28 percent lower in smokers who used e-cigarettes compared to smokers who didn’t. They write: “As currently being used, e-cigarettes are associated with significantly less quitting among smokers.”

This result is completely contradictory to the results of the Cochrane review of the same evidence, so what’s going on?

The issue ultimately comes down to the choice of studies included in the analysis. If you do a meta-analysis with excellent-quality research that’s similar enough to be looked at all together (as if it’s one giant study), then you’ll get a pretty reliable result. If you do a meta-analysis composed of poor-quality research, you’ll get an unreliable result. In other words: junk in; junk out.

The “junk” in this case comes from studies with a clear “selection bias.” These studies are typified by this one, which looked at 2,758 smokers who called a quit smoking helpline in the US and followed up with them seven months later to see how many had been successful. The results showed that those who’d used e-cigarettes prior to calling the quit line were less likely to have quit smoking at follow up compared to people who hadn’t used them previously. The key here is that the participants in the vaping group of the study had already tried vaping but hadn’t quit smoking. In other words, if you’d tried vaping and quit smoking, you wouldn’t be included in the study: it samples the failures and ignores the successes. Dr. Michael Siegel drives this point home in a blog post on the study.

These types of studies being included meant the meta-analysis was panned by experts. Clive Bates eviscerated it in detail, but a comment from Professor Peter Hajek illustrates the problem nicely. After calling it “grossly misleading” and commenting that “The same approach would show that proven stop-smoking medications do not help or even undermine quitting,” he writes:

Here is an analogy: Imagine you recruit people who absolutely cannot play piano. There will be some among them who had one piano lesson in the past. People who acquired any skills at all are not in the sample, only those that were hopeless at it are included. You compare musical ability in those who did and those who did not take a lesson, find a difference, and report that taking piano lessons harms your musical ability. The reason for your finding is that all those whose skills improved due to the lessons are not in the sample, but it would not necessarily be obvious to readers.

These errors were all lumped into the meta-analysis, and this renders it essentially worthless. In a nutshell, the reason the Cochrane group’s conclusions disagree so much with the result of this analysis is that the Cochrane team were credible and competent scientists.

Recent Studies on Vaping for Quitting Smoking

A few recent studies drive home the key point of this blog post: vaping does help smokers quit.

One study from Dr. Konstantinos Farsalinos analyses data from the 2016 and 2017 National Health Interview Surveys, specifically looking at how common vaping is in recent and not-so-recent quitters. This is an indirect approach, but a clever way of looking at the issue from a different angle.

The results show that former smokers who quit less than a year ago have higher vaping rates than smokers who quit one to three years ago (16.8 vs. 15 percent) and both of these are substantially higher than vaping rates in smokers who quit four to six years ago or longer ago (10.5 and 0.7 percent of whom vape, respectively). When researchers ignored the length of time smokers had quit, there was no association between quitting smoking and using an e-cigarette, but when this was taken into account, smokers who quit less than a year ago were 3.4 times more likely to vape, and those who quit one to three years ago were 2.5 times more likely to vape.

Broadly, in recent years, there is a strong association between vaping and having quit smoking.

The other two studies are randomized controlled trials, providing much more direct evidence of the effectiveness of vaping. The first was published in January, and recruited 210 smokers, who were randomized to either nicotine e-cigs, no-nicotine e-cigs or a control group and followed up with three months later. The results showed that one in four smokers in the e-cig groups had quit smoking at three months, compared to one in ten in the control group. Researchers compared daily smoking at the end of the study between the three groups, and found that the nicotine e-cig group reduced smoking most, followed by the no nicotine e-cig group and finally the control group.

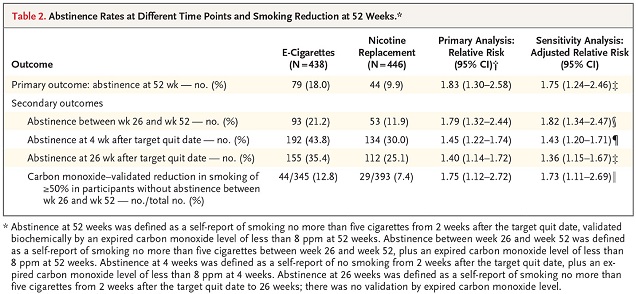

The final study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine and included 886 smokers who attended stop smoking services in the UK. They were randomized to either receive an NRT product of their choice (with a three month supply) or a second-generation e-cig with a single bottle of 18 mg/ml e-juice, and a recommendation to buy more juice in their chosen flavor and strength afterwards. They all received behavioral support for at least a month along with the products.

After a year, 18 percent of people in the vaping group had quit smoking, compared to 9.9 percent in the NRT group. There was a huge difference in the numbers who quit still using the product, with 80 percent of vapers who quit still vaping compared to 9 percent of the NRT group, but the quit-rates are still impressive. Additionally, the criticism of the previous trial comparing vaping to NRT (that it was harder for participants to get patches than e-cigs) effectively applies in reverse to this trial (because NRT was supplied for much longer), but the results are even more supportive of vaping’s effectiveness.

Putting it All Together: Does Vaping Help Smokers Quit?

So now, let’s look at all of the evidence and what it tells us.

- Smokers say it helps.

- The method seems sound.

- Smoking rates decline when people start vaping in a population.

- The early evidence was limited but broadly positive.

- Claims vaping doesn’t help are based on low-quality evidence.

- Recent studies strongly support the effectiveness of vaping, including randomized controlled trials.

Perhaps you can see all of this and still hold out on forming an opinion. You might want at least 10 randomized controlled trials before you feel comfortable. You might even have some niggling issues with the recent research.

But there is only so long you can maintain this skepticism in the face of mounting evidence. I would argue that there is more than enough evidence to get confident about recommending vaping to smokers who want to quit. The evidence is almost entirely positive and realistically speaking, we should have never expected anything different.

The benefits are obvious. Even the most ardent doubters are fast-approaching the point where they have to face the facts: vaping helps smokers quit, and holds massive promise for smokers all around the world, as long as it isn’t crushed by over-reaching regulations before it lives up to its potential.