Even in the wake of the vapocalypse, with the lung illness still affecting people across America (likely due to illicit THC cartridges made using vitamin E acetate), the response from the government and public health bodies has still maintained its laser-like focus on teens and youths vaping. The story is the same as always: there is an “epidemic” of youth vaping, and we’re told that innocent, wide-eyed kids who’d never have smoked otherwise are lured into nicotine use and ultimately smoking by the “child-friendly flavors” many e-liquids and pods are available in.

The “epidemic” was declared last year, as “preliminary data” (read: not available to analyze for other researchers) from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) showed a shocking rise in past-month vaping among middle and high school students. Like Trump declaring an emergency at the southern border to bolster the case for his anti-immigration agenda, the “epidemic” was used – and still is being used – as justification for pushing through harsh restrictions on vaping. The target of these is (usually) the flavored products that many adults credit with playing a key role in their transition from smoking to vaping.

The big question is: is there really an epidemic of youth vaping? Declaring one while holding the key data close to your chest is easy, but maintaining it when the data is open for anybody to pore through is much more difficult.

A new study does just this. Martin J. Jarvis, Robert J. West and Jamie Brown from University College London have taken a look at the details behind the epidemic, and the results call into question five of the key claims made to justify this epidemic.

The National Youth Tobacco Survey and the Youth Vaping “Epidemic”

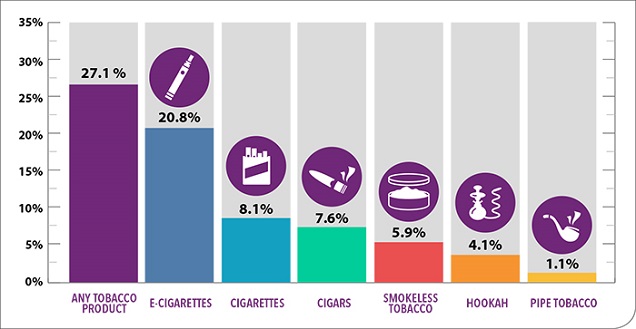

Before getting into the details of the study, the key piece of evidence used by US health authorities when discussing this is the NYTS. This is an anonymous annual survey completed by middle and high school students from across the US, aiming to produce a nationally-representative “snapshot” of tobacco use across the country based on students in the 6th to the 12th grade. It covers most types of tobacco: cigarettes, cigars, other combustibles (e.g. hookahs), non-combustibles like chewing tobacco, snuff and snus, as well as nicotine products like e-cigarettes. They survey classes anybody who’s used a product in the past 30 days as a “current” user, and it also asks about ever having tried the product in question.

These are the two key measures authorities focus on when the results are reported each year. Press releases talk about the rise in “current” e-cigarette use, for example, amid continually-declining smoking rates. This is what they said about the “epidemic” last year: for high school students, the 2018 NYTS showed an increase of 78% in current vaping. The study quotes ex-FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who said:

The data show that kids using e-cigarettes are going to be more likely to try combustible cigarettes later. This is a large pool of future risk. … The data from this nationally representative survey…. show astonishing increases in kids’ use of e-cigarettes and other ENDS , reversing years of favorable trends in our nation’s fight to prevent youth addiction to tobacco products. These data shock my conscience.

The increase in vaping was real, of course. In 2017, 11.7% of high school students reported past-month vaping, while in 2018 it was 20.8% – a 78% increase just like they said. However, from this point onwards the picture painted by the data doesn’t really match the impression you’d have gotten from official statements on the topic.

1 – Never-Smoking Teens are Much Less Likely to Vape

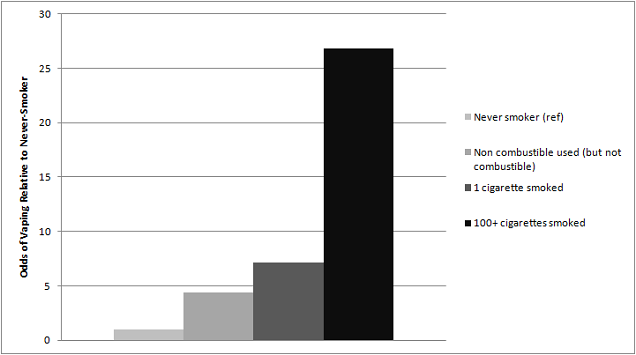

The first problem with the narrative of an explosion in vaping among impressionable young teens is that the data shows that teens who smoke or who had smoked in the past are much more likely to vape. For teens who’d never smoked, in 2017, 2.9% had vaped in the past 30 days, and this rose to 8.4% in 2018. For those who’d smoked more than 100 cigarettes (i.e. 5 packs) in their lives, past-month vaping rose from 57.2% in 2017 to 71% in 2018.

The researchers compiled odds ratios to really make the data clear. Compared with teens who’d never used tobacco (using the 2018 data), those who’d used a non-combustible (but not a combustible product) were 4.4 times more likely to be a past-month vaper, for those who’d smoked one cigarette in the past, the odds were 7.1 times higher, and for those who’d smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime, the odds were a huge 26.8 times higher to be a past-month vaper than for a never-smoker. The 2017 data shows a similar picture.

In a nutshell, the chances of being a past month vaper are much higher for those who’d already smoked or at least used nicotine in some form.

2 – They Aren’t Vaping That Often

A key part of the narrative surrounding youth vaping relates to addiction. The fear is – understandably – that teens who’ve never smoked will pick up vaping and become addicted to nicotine. While the last point already shows that teens who’ve already smoked or at least used nicotine are far more likely to be current vapers, the next part of the progression is on shaky ground too.

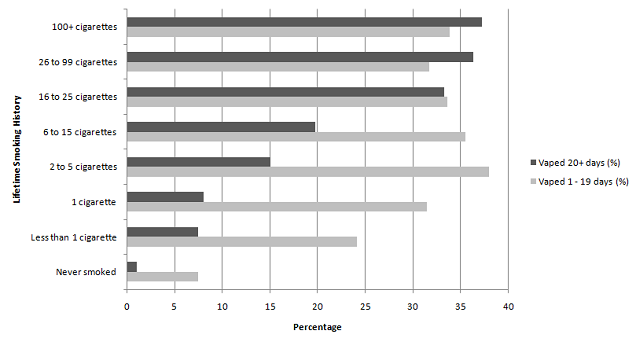

The big problem is that past month vaping doesn’t mean “vaping all the time,” as “current vaper” might imply to a casual reader. Frequent use is what many people would picture, and if you define that as 20 or more days in the past month, the picture changes substantially. Only about a quarter of past month vapers had vaped frequently in either year, specifically 19.9% in 2017 and 28.4% in 2018.

And when you combine this with their smoking status, the reality falls sharply into focus. For those who’d never used tobacco, just 0.1% of never tobacco users vaped frequently in 2017, rising to 1 percent in 2018. In contrast, those who’d smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime had frequent vaping rates of 26.8% in 2017 and 37.2% in 2018.

Of course, the rise in frequent vaping among never smoking teens from 2017 to 2018 is still quite large, proportionally speaking, but in absolute terms the numbers are unavoidably tiny.

3 – They Don’t Seem to Be Addicted

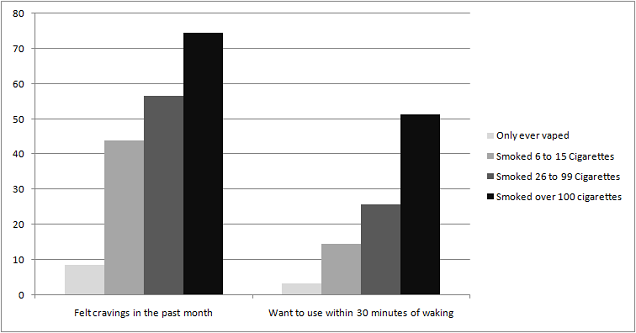

But that isn’t the end of the issues for the claim that there is an explosion in youth nicotine addiction as a result of vaping. The NYTS also asks some questions to indicate the level of dependence in the respondents, specifically, whether the teens have a craving for the tobacco product and how soon after waking up they want to use one. Of course, reporting cravings and using soon after waking are signs of dependence.

Only 3.8% of past-month vapers reported cravings, and 3.1% said they wanted to use tobacco products within 30 minutes of waking up. There is a problem with the terminology here, though, because teens who only vape didn’t really see themselves as “tobacco product” users at all. For example, when asked if they were thinking about quitting all “tobacco products,” about half of those who only vaped chose “I do not use tobacco products.”

The authors point out that in response to “How soon after you wake up do you want to use a tobacco product?” a massive 60.4% of respondents who were current vapers but had never smoked or used another tobacco product said “I do not want to use tobacco” and another 28.1% said “I rarely want to use tobacco.” Around 13 percent had only vaped on one day of their life, and 49 percent said had only vaped on between 1 and 10 days. Needless to say, this doesn’t appear to reflect widespread dependence.

The past-month vapers who’d smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lives, on the other hand, responded in a completely different way. Among them, 74.5% said they’d had cravings and 51.4% wanted to smoke within 30 minutes of waking up.

Although there is some confusion caused by the nonsensical definition of e-cigarettes as “tobacco products,” outside of a very specific legal context, it’s clear that addiction is much more common in smokers who currently vape than in non-smokers who vaped in the past month. Even if you argue that the misunderstanding of the question led to the vapers looking less addicted than they are (for example, they might have wanted to vape within 30 minutes of waking but not seen it as using a “tobacco product”), this result really strikes against the idea of a gateway. In either case, it’s a big blow to the US narrative around youth vaping.

4 – Most Youth Smokers Start with Cigarettes

The “gateway” hypothesis doesn’t look too strong after an analysis of the NYTS data either. The idea is that after having developed a nicotine addiction through vaping (which most don’t seem to) and having not tried any other tobacco products previously (which is also much less likely), teens will switch over to cigarettes and develop a life-long problem.

The data used to address this claim came from the 2014 and 2015 surveys, because the questions weren’t asked in the 2017 or 2018 surveys. The authors don’t dwell on this point, but it’s really worth repeating: in the midst of an “epidemic” of vaping and widespread fear that it will lead to smoking in future, they stopped asking which use came first. This is an incredible fact that raises serious questions about their approach to the issue.

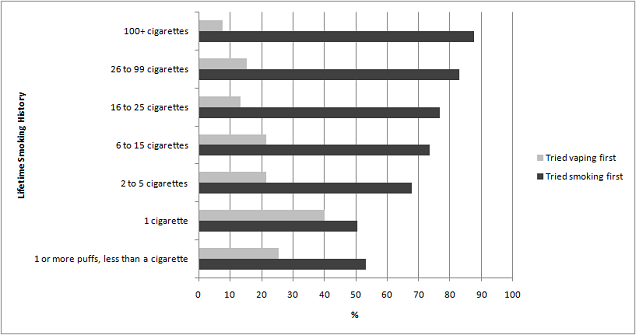

In 2014, 75.6% of past-month vapers who’d also smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime said cigarettes were the first tobacco product they’d used, and just 2.2% said they’d vaped before smoking. For those who’d only had a few puffs of a cigarette in their life, 49.3% had started with cigarettes and 18.8% had vaped first. In 2015, cigarettes were the first product used for 87.7% of past-month vapers, with just 7.6% saying e-cigarettes were the first product they’d used. For those who’d just had a few puffs of a cigarette, 53.1% started with cigarettes and 25.4% had tried vaping first. The authors comment, “the more cigarettes students reported having smoked in their lifetime, the higher the chances were that cigarettes were the first product used.”

5 – Smoking is Continuing to Decline as Vaping Increases

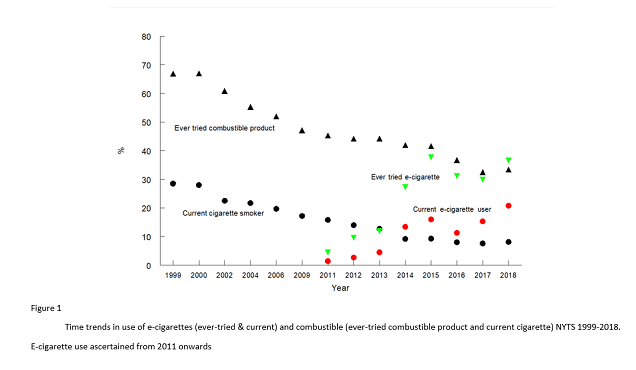

So the gateway hypothesis doesn’t really seem to be an issue based on the only data that can really be used to track it, but the overall smoking and vaping rates could offer some insight into the issue too. The smoking rate in high school students declined from 28.5% in 1999 to 8.1% in 2018, and the number who’ve ever tried a combustible product has been cut in half in that time. The authors point out that the advent of vaping has had little impact on this trend, if any at all.

There are attempts from both sides of the debate to show the impact of e-cigarettes on youth smoking rates, but the authors’ claim that it’s had no discernable impact on the already-declining cigarette and combustible product use (from this study, at least) does seem fair looking at the graph. If you choose your start and end-point closely, you might be able to whip together a narrative, but it’s hard to look at the data with an open mind and really see an impact in either direction.

Of course, e-cigarettes do help smokers quit, and there is no reasonable doubt about this point. But the best we can conclude from this basic-level evidence is that the rise in vaping hasn’t impacted the decline in smoking. If the gateway effect were true (especially if it was happening a lot), you would expect to see some reduction in the decline in smoking (if not an increase), but this simply isn’t happening.

In the Discussion section of the paper, the authors point out:

While it may well be the case that in some individual instances initial trying of an e-cigarette led on to trying and using cigarettes, the data strongly suggest that this is not the dominant pattern observed at the level of the whole population …. At the population level, therefore, the NYTS fails to give evidence of e-cigarettes acting as a gateway to smoking in adolescents.

The Epidemic That Wasn’t

After pointing out that the paper is merely intended as an analysis of the evidence from the NYTS rather than a critique of the US regulatory approach, the authors wrap up the paper in a pretty devastating style:

We find a gaping chasm between the vision of an epidemic of e-cigarette use threatening to engulf a new generation in nicotine addiction and the reality of the evidence contained in the NYTS.

It’s understandable that the authors don’t want to criticize specific policy objectives: they are scientists, not activists. But we have more liberty to call things as we see them. The data from the NYTS shows an increase in vaping, but it does not in any way show an epidemic. It’s hard to see the decision to declare an epidemic before the data was released as anything but a calculated, cynical move to drum up concern. Sober analysis of the facts in no way supports the hysteria, and it hasn’t ever since vaping was first included in the NYTS.

It is no coincidence that the NYTS asks about the specific number of days the students vaped but they never report it in the initial MMWR releases about the data. It is no coincidence that they stopped asking about the first product used while continuing to imply a gateway effect. It is no coincidence that people who cite the NYTS don’t show as much restraint about suggesting policy measures as the authors of this study did.

Make no mistake, all of the researchers on this study did was look at the exact same data used to declare an epidemic last year. There are two possibilities: the authors of this study are maliciously cherry-picking in order to downplay an epidemic of vaping that actually exists, or the US public health establishment is doing exactly that to create the impression of an epidemic that doesn’t exist.

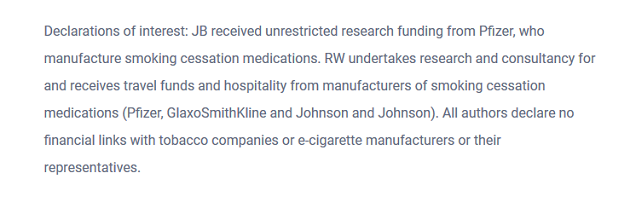

The authors of this study are probably funded by Big Vaping, right? That must be what’s going on? Well, let’s have a look…

Ah. Interesting. The question is: what could possibly motivate them to do this? And the answer is easy to find: the data is publicly-accessible. Look at it. There is no epidemic; the US public is being hoodwinked. The researchers are simply telling the truth.