The e-cigarette debate is pretty heated. On one side, there are legions of anti-smokers turned anti-vapers warning the smokers of the world away from harm reduction because of the potential for comparably miniscule levels of harm, and on the other you have us vapers, fervent in our support of the devices that helped us quit smoking and eager to jump down the throats of anybody repeating unsupported or downright false statements about e-cigarettes. We’ve spent plenty of time tackling anti-vaping myths since the site got started, but it isn’t just those opposed to vaping that often spout mistruths or plain misleading statements. In fact, there are quite a few pro-vaping myths and misleading arguments that we should stop repeating if we want to be taken seriously. (Don’t worry, “it’s just water vapor” isn’t one of them, because nobody says that.)

1 – “E-Liquid Only Has Four Ingredients”

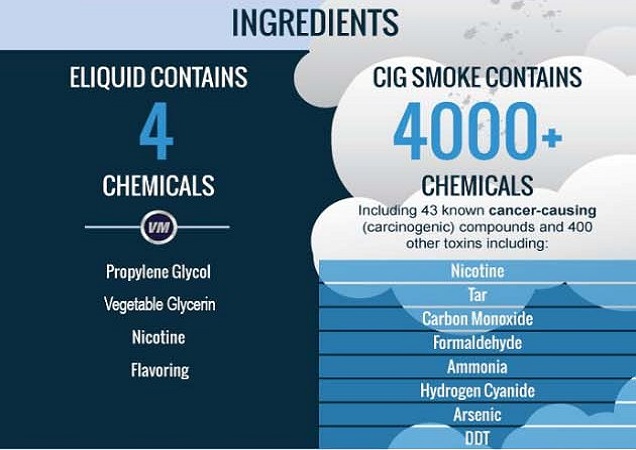

We’ve all heard it. “Cigarettes contain thousands of chemicals with about 70 carcinogens, whereas e-cigs just contain four: PG, VG, nicotine and flavorings.” In essence, the core point is true – e-cig vapor does contain vastly fewer chemicals than tobacco smoke, and especially less toxic ones – but the specific formulation (“four ingredients/chemicals”) is blatantly incorrect.

The main problem is that “flavorings” does not, in any way whatsoever, class as a single ingredient. Among others, “flavorings” refers to ethyl maltol, vanillin, ethyl vanillin, benzaldehyde, ethyl butyrate, menthol and ethyl acetate. There are also trace levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in e-liquids (and vapor). Of course, I’m not alleging that this is something to be concerned about – although there is uncertainty about the risks of inhaling flavorings, the levels are low and it’s still undeniably safer than smoking.

And that isn’t even the whole problem with such statements. The cigarette figure – 7,000, 5,000, 4,000 or whichever number people settle on – is invariably from smoke rather than un-combusted cigarettes. If the same logic is applied to e-cigarettes, we’d also have to acknowledge the presence of all the chemicals in the vapor, including very low levels of formaldehyde, acrolein and various metals. The point can still be made honestly, but simply saying e-cigs contain “four ingredients” is clearly misleading.

What We Can Say Instead

Note: In response to feedback, this post has been updated to include these suggestions for making the same arguments without relying on myths or misinformation. See Carl V. Phillips' comment below about these updates, which offers valuable commentary on their validity and how well they replace the original claims.

E-cigarette vapor contains vastly fewer chemicals than cigarette smoke, and any toxic ones present are in quantities not expected to cause harm. Levels of toxic chemicals in vapor have been consistently shown to be anything from tens to hundreds and right up to thousands of times lower than in smoke.

2 – “All of the Ingredients in E-Cigs Are Generally Recognized as Safe”

This is technically true (just like saying “e-cigs contain carcinogens” is technically true), but it’s pretty misleading. The “generally recognized as safe” label, particularly when considering food-safe flavorings, does not apply to inhaling those chemicals, only ingesting them.

The perfect example for this is diacetyl, which is generally recognized as safe, but is not safe for inhalation, and a study by Dr. Konstantinos Farsalinos brought this to the attention of the vaping industry after finding it in several tested e-liquids. The Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association has addressed the issues with such claims, and although they take it a little far – claiming, for some unknown reason, that established safety limits for workplace inhalation don’t apply to inhalation through e-cigs – there is a genuine point in there.

Inhaling flavorings probably isn’t going to kill you, but it’s one area where we really do lack information about the risks, and saying they’re “generally recognized as safe” is undoubtedly misleading.

What We Can Say Instead

Something else. Previously, I'd included a (weak) alternative here, but Carl V. Phillips' comment below is spot on: this argument should just be ditched entirely.

3 – “PG is Used in Asthma Inhalers”

This is an interesting one. I’ve seen the argument made in many places, but whenever I made the decision to try to actually find an asthma inhaler or a nebulizer which uses PG, I’ve been completely unable to.

A poster on reddit even asked outright if anybody could prove this statement, and the result was basically that nobody could. There is one study looking at the potential to use PG as a carrier for an inhaled medicine and another which mentions that PG or ethanol may be used as a cosolvent in nebulizers, but no evidence presented of an asthma inhaler or nebulizer that is actually used today containing PG.

It’s very hard to prove it isn’t used – since there could always be something we didn’t find – but a little research shows that Ventolin (albuterol), Airomir (salbutamol), Salamol (salbutamol) and the Maxair Autohaler (pirbuterol) definitely do not contain PG, and I’m sure you could go on to check out other options too.

We’d love to be proven wrong on this one (and will update/remove this as needed), but it seems like this argument – especially for inhalers – is total bullshit.

For nebulizers, it could be that it’s occasionally used (though, again, we can’t find a concrete example), but studies have shown that – as many vapers will know – some people find PG very irritating to the throat, so inhaled medicines using less of it are generally better tolerated.

Additionally, it wouldn’t even be a very good argument if an inhaler or nebulizer was found to contain PG. There’s a big, big difference between inhaling a few puffs of an asthma inhaler and chain-vaping several hundred puffs per day. And you hardly see asthmatics blowing out clouds, so we’re clearly consuming larger quantities of PG with each puff too.

It’s absurd to be concerned about small quantities of things like nitrosamines in e-cig vapor because the dose makes the poison, but it’s just as ridiculous (if not more so) to assume that just because a small amount of something is safe then a much larger amount is nothing to worry about either. In short, asthma inhalers and vaping are not comparable, even if inhalers did contain PG (which they don’t).

As for why this argument has gained so much traction, my only guess is for the same reason I want it to be true: it’s so powerful to be able to say, “well, even asthmatics can inhale PG without problems, so worrying about it in e-cig vapor is silly.” But when you really want something to be true, you don’t have much motivation to go and check out whether or not it’s really the case. Much like those who repeat anti-vaping arguments without fact-checking, this one in particular shows that we vapers can do exactly the same thing.

What We Can Say Instead

Propylene glycol has been well-studied, and is used in theatrical fog machines, some air disinfectants and a multitude of other consumer products. While it may not be entirely safe to inhale directly, any risks it poses pale in comparison to those of smoking.

4 – “Nobody Has Died from Vaping”

Another claim you often see is “nobody dies from vaping!” or even comparisons of the statistics for smoking deaths and the lack of deaths from vaping.

To see the problem, you can just imagine cigarettes had only been on the market for 10 years or so. Would we be seeing any deaths from smoking? Well, probably not, no.

For one, smoking generally reduces your lifespan by about 10 years, and the risks overall increase the longer you’ve been smoking, so even on that simple basis you probably wouldn’t see deaths from smoking a decade after cigarettes were introduced. The concept of “pack-years” is used, where one pack-year is the equivalent of smoking a pack of cigarettes a day for a year, and generally (as you’d expect) the risk of various conditions increases with pack-years. There are increased risks after 10 pack-years, but it really starts getting serious quite a bit further down the line.

On top of this, the average age of diagnosis with lung cancer is 70, the average age of a first heart attack is 66, and COPD is normally diagnosed in people aged 40 or older. In general, smoking-related illnesses strike quite late in life. That’s why the figure is 10 years of lost life, rather than 40 or so.

In short, after 10 years of smoking, chances are you’ll still be alive, so the lack of deaths from vaping at present means pretty much nothing. And that’s before you get onto the whole issue of establishing that vaping rather than something else (e.g. the vaper’s smoking history) is to blame for the deaths and thereby being able to say “vaping kills n people per year.” We might be able to do so in 20 or 30 years, but right now we’re far from being able to honestly compare death rates.

What We Can Say Instead

After almost a decade of vaping, no related health problems have been documented in vapers, and the evidence to date shows that vaping is substantially safer than smoking.

5 – “Cigarettes Have 750 Times More Diacetyl Than E-Liquids”

Whenever the issue of diacetyl in e-juice is brought up, you’ll see several vapers commenting that “But cigarettes contain 750 times more diacetyl than e-liquids!”

While the general message – that cigarettes contain more diacetyl than e-liquids – is true, the actual figure is complete bullshit. The origin of the figure is Michael Siegel’s blog post in response to the most recent diacetyl study, where he calculated the average diacetyl levels in the e-liquids tested (including those with no diacetyl) as 9 μg per ml (technically per cartridge, which is a little less but close enough). He then pulled up some comparative figures for cigarettes.

Then, undoubtedly because he isn’t too familiar with vapers’ habits (or the limited evidence looking at how much people consume – one example here), he made the comparison based on consumption of 1 ml of e-liquid per day vs. a pack of cigarettes. If you can remember a day recently when you only consumed 1 ml of e-liquid, it’s safe to say you were either also smoking or you forgot your e-cig when you went to work. Virtually no full time vapers, in this age of 150 W mods and sub-ohm tanks, is consuming just 1 ml per day.

This wouldn’t have been much of an issue, because Siegel made it clear – in the original blog post – that this was a comparison between daily intakes for smokers and vapers. However, in Guy Bentley’s Daily Caller story about Siegel’s blog post, even though he did clarify in the post, the headline was “‘Popcorn lung’ chemical 750 times greater in tobacco cigarettes.” This was made even worse by Siegel explicitly claiming “The levels of diacetyl are about 750 times lower than in cigarettes” in a more recent blog post, without qualifying the claim. It seems even if you turn against tobacco control – as Siegel admirably did in response to the more nonsensical claims about second-hand smoke – ridding yourself of the truth-stretching habits isn’t so easy.

To be clear, a figure somewhere in the region of 100 and 200 times lower is completely accurate. So why make such a misleading claim? The answer appears to be because 750 times sounds like such an extreme difference that it makes the inevitable follow-up point seem even stronger.

What We Can Say Instead

Cigarette smoke has hundreds of times more diacetyl than e-cigarette vapor. A day of vaping instead of smoking reduces your diacetyl intake by up to 240 times.

6 – “Smokers Don’t Get Popcorn Lung from the Diacetyl in Cigarettes”

So after laying the groundwork by exaggerating the gulf between diacetyl level in e-liquids and cigarettes, the follow-up point is that “smokers don’t even get popcorn lung!”

Put together, these points make the concern about diacetyl seem almost laughable. So cigarettes contain way more diacetyl than e-cigs and smokers don’t even get this nightmarish “popcorn lung disease” we hear so much about.

But, as Dr. Farsalinos pointed out in his paper looking at diacetyl in e-juice, the claim that smokers don’t get popcorn lung isn’t as reliable as it may seem. It’s true that not many smokers are diagnosed with popcorn lung, but you can’t read too much into that.

Firstly, popcorn lung is fairly rare, even in those exposed to diacetyl in industrial settings; the most common consequence is simply impaired lung functioning and general respiratory issues. Secondly, diagnosing popcorn lung is pretty difficult, and misdiagnosis is very common.

So smokers might not be diagnosed with popcorn lung very often, but they are regularly diagnosed with COPD, a more general obstructive lung condition, and this happens a lot more than you’d expect even heavily diacetyl-exposed people to be diagnosed with popcorn lung. Of course, smoke contains tons of bad chemicals, but it’s not exactly easy to say that diacetyl doesn’t contribute to the problems smokers have. Plus, when presented with a smoker with lung problems, is a doctor going to jump to popcorn lung as a diagnosis, or just assume it’s COPD?

None of this means that diacetyl in e-cigarettes is anything to worry about – you can learn more about what we know here – but brushing it aside with “smokers don’t get popcorn lung” is a severely flawed argument.

What We Can Say Instead

While diacetyl may contribute to the lung problems from smoking, there is no solid evidence of risk from inhaling it in quantities like those seen in e-juice, although it is possible. If risks are uncovered, diacetyl can easily be removed from e-juice or otherwise avoided by vapers.

Conclusion – Scoring An Own Goal?

Inevitably, this may seem like a vaping advocate scoring an “own goal,” to borrow a phrase originally used in a different context. Am I just being a jerk and bashing e-cigs, when they get unfairly criticized way too much already? I don’t think so. For one, I am not blindly pro-vaping. My main aim is to give smokers and vapers accurate information from which they can make decisions about whether they want to vape. If it turns out vaping has serious risks, I will happily explain them as best I can.

But more importantly, since I am still ultimately pro-vaping (just not blindly so), when is it appropriate to score goals against your own team? In training. Pointing out weaknesses in your own side’s defense and drawing attention to glaring mistakes helps us avoid those mistakes in the future. It makes it less likely opponents will be able to score an easy goal past us.

To ditch the analogy: if we make flawed, misleading arguments to support vaping, anybody sufficiently knowledgeable will be able to pick them apart and make us look like we’re either being purposefully deceptive or dumb. The only way to make sure your position is strong – and more importantly, accurate – is to subject it to just as much scrutiny as you would arguments from those who disagree with you.

So am I scoring an own goal? Yes, but that’s a good thing if we don’t want a weak defense.