So, people are vaping caffeine now. It was only a matter of time before the occasional caffeine-spiked e-liquid turned into a full-blown purpose-built caffeine vaporizer, but the question remains as to whether there’s any point in using one. Companies like Eagle Energy Vapor claim that the benefit is an “instant hit” of caffeine – for those with such busy lives that drinking a cup of coffee is an unthinkably slow process – and the fact that there are no calories – because clearly the reason we have a problem with obesity isn’t all the fast food, goliath portions and the lack of exercise, it’s all the coffee we drink. While I’ll likely be sticking to inhaling my nicotine and drinking my caffeine – because I’m old fashioned like that – is caffeine vaping set to become the next big thing, or is it just another fad?

Too Long; Didn’t Read

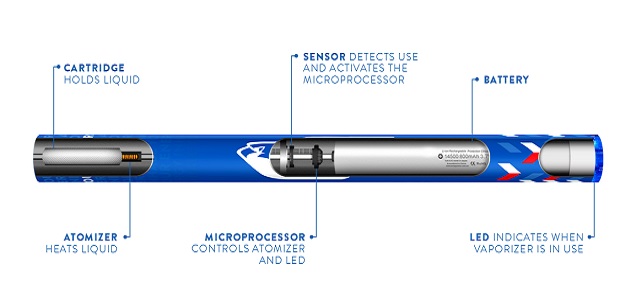

- Caffeine vaporizers, like the one from Eagle Energy Vapor, work just like disposable e-cigs, with caffeine in place of nicotine.

- The manufacturers claim that 10 to 20 puffs is equivalent to drinking a cup of coffee, because the caffeine has a more direct route to the bloodstream.

- There is debate as to whether vaping caffeine would really be more efficient than drinking it, due to its physical properties, but those who've tried it seem unanimously impressed.

- As with normal vaping, the long-term risks are unknown, but there is less evidence on inhaled caffeine than there is for nicotine.

- Although caffeine is reasonably safe when ingested, inhaling anything carries risks, and the reasons for taking that risk instead of simply drinking a cup of coffee are unclear.

Caffeine Vaporizers vs. Coffee

The caffeine vaporizer from Eagle Energy is pretty much a disposable e-cigarette filled with a mixture of guarana extract (pure caffeine), taurine and ginseng (with no mention of PG or VG, although it seems like they – or similar chemicals – would have to be involved), vaporizing the mixture as you puff in the manner of early cigalikes. It’s supposed to offer about 2 milligrams of caffeine per puff, and each disposable (supposedly) offers about 500 puffs. Although a cup of coffee contains around 95 to 200 mg, the recommended “serving” for vape-able caffeine is 20 to 40 mg, or about 10 to 20 puffs. A New York Times reporter got a caffeine rush after about 10 puffs, comparing the feeling to drinking a Red Bull rather than having a cup of coffee. Huffington Post staff were similarly impressed with the results.

The reason for the vast difference between how much caffeine is present in a cup of coffee and how much caffeine you need to vape to feel the effects is that inhalation is generally a more efficient method of drug delivery. When you drink coffee, it has to be digested before the drug reaches your blood stream, but inhalation skips all of that: it goes straight to your lungs and then into your blood. This means you don’t need as much to get the job done, but it also means it’s a bit easier to get a substantial caffeine buzz going, and potentially, to consume a little too much caffeine.

There are plenty of other caffeine vaporizers – or at least similar ideas – on the market. One group of inhalers, from AeroLife, claims to be a “dietary supplement” powder, but in fact just shoots a flavored blast of caffeine powder down your throat – the FDA issued a warning letter to them due to their conflicting claims that it was meant for ingestion but also “breathable,” as well as some eerily familiar comments about “the children.” Rush Energy Vapor has a more disposable e-cig like approach, pretty much the same as Eagle Energy Vapor, but being straightforward about the fact that they use PG and VG, with caffeine in place of nicotine and little other difference.

However, there are some criticisms of the whole idea, based on the fact that caffeine sublimates (goes directly from a solid to a gas) and would likely re-deposit as a solid into your airways if you tried to vape it. It’s unclear whether the manufacturers have overcome this issue, but generally speaking there is a lot of skepticism about whether vaporizing caffeine would be effective at all. Some argue that it wouldn’t be absorbed – or at least not that efficiently – through the lungs, and that ingesting it is actually the better way to get your dose. However, those who've tried it seem convinced it works: it could be a placebo effect, but it probably just means that the potential issues have been overcome.

Is Vaping Caffeine Safe?

As with vaping, there is some concern about the potential risks of inhaling caffeinated vapor. As you may expect given my position on vaping, I’m not eager to bang the drum and harp on about how “we don’t know the risks” yet and how “inhaling a stimulant isn’t advised” and so on. I consume caffeine (in the traditional fashion) and nicotine using a method that hasn’t been studied long-term, so it would be quite hypocritical of me to go on about how you shouldn’t vape caffeine because of the potential risks.

As far as I’m concerned, as long as you understand the risk you’re taking – given that there is genuine uncertainty, as with vaping, and this time there doesn’t even appear to be much in the way of animal studies (which we do have for nicotine, PG and VG) to base an opinion on – then feel free to do whatever you want to.

Caffeine, a substance most of us consume every day (taking in an average of 300 mg per day), obviously isn’t much to worry about on its own. There are some potential risks, but it’s never been linked to serious health effects. It is mildly addictive, but there are also some positive effects too. We all know that too much coffee can keep you awake, and it can also lead to anxiety in some cases, but the main risk from caffeine in the form of inhalation seems to be in consuming too much.

Having too much will give you headaches (which will likely stop you from going much further), but serious overdoses could be dangerous – leading to rapid heartbeat, vomiting, diarrhea, disorientation and possibly seizures or death. However, the toxic dose of caffeine is estimated at about 150 to 200 mg per kg, which works out to about 118 cups of coffee. If we take 15 puffs as equivalent to a cup (as Eagle Energy claim), then it would require an implausible 1,770 puffs to overdose on caffeine through vaping, and you’d need to take them fairly quickly (and this is all assuming it can be efficiently absorbed through inhalation). In short, unless you have a set of mechanical lungs, it’s probably not happening.

The main issue, though, is a simple question: why take the risk of vaping caffeine instead of drinking it? For nicotine, vapers have been conditioned to consume it via inhalation through years of smoking, but the habitual coffee-drinker has no such motivation. Inhaling something that isn’t air is generally – and understandably – not recommended, so is it really worth consuming the same substance in a way that likely carries more risks, when you could just as easily have a cup of coffee or an energy drink?

Perhaps in some situations when it isn’t feasible to carry beverages with you, it would be understandable (if you really need your caffeine) but given the uncertainty, the usefulness of vaping caffeine seems limited. Vaping nicotine is replacing an undeniably deadly habit with one that probably only carries very minor risks – a definite net gain – but vaping caffeine seems to be trading one innocuous habit for a probably slightly more dangerous one. It doesn’t seem like it’s going to be a serious health problem, but it does seem like an unnecessary risk.

Vaping for the Sake of Vaping? Why the Problem with Nicotine?

This whole vaping caffeine thing really seems to come down to the fact that vaping – although superficially pretty darn dorky – is quite cool at the moment: vaping caffeine just seems like a way to get in on the trend. The curious thing is why all of these manufacturers go to such lengths to point out how it’s “nicotine free.” What makes one mild stimulant so different from another?

Perhaps this is a consequence of nicotine’s bad reputation – for addictiveness and much more – but strangely, it seems that vaping nicotine could actually be a better idea than vaping caffeine. That’s not to say it’s necessarily safer, but more that we actually have experience with (and growing evidence for) inhaling nicotine that suggests that it’s not such a huge deal in itself. Whether inhaling PG, VG and food flavorings long term is a good idea is another issue entirely, but with some caffeine vaporizers using these anyway, caffeine merely piles one extra source of uncertainty onto the decision.

Is the notion of not having to drink a cup of coffee – which contains (gasp!) calories – really worth taking the risk? Do you really need a faster hit of caffeine? If you think so, then by all means go for it (and I sincerely hope it doesn’t cause any problems in the long-term), but personally, consuming caffeine the traditional way seems just fine to me.