While in the UK, the Royal College of Physicians and Public Health England wholeheartedly endorse vaping and actively refute many of the absurd claims made in opposition of e-cigs, the CDC’s prohibitionist, alarmist mindset continues unabated. We’ve spent some time in the past looking at the CDC’s misleading reporting of the results of the results of the National Youth Tobacco Surveys from 2011 to 2014, and the release of the 2015 data last month was accompanied by the usual raft of misleading interpretations, scaremongering and anti-vaping nonsense.

So instead of covering the individual report, this time around I’m taking a broader look at the CDC’s approach to vaping. And by “approach to,” I mean “annual baseless attacks on” and “refusal to acknowledge the benefits of.” If you think we should trust the CDC – our ‘respected’ public health organization – on the issue of vaping, this post will show you exactly why you’re wrong.

Summary (TL;DR)

- The CDC’s definition of “current user” in the National Youth Tobacco Survey captures many teens who are experimenting, rather than vaping regularly.

- In the 2014 and 2015 surveys, they asked how many days the teens vaped during the past month, but didn’t report the answers with the bulk of the results. The data from 2014 shows that only 0.55 percent of never-smokers vaped on more than 5 days out of the past month.

- Early attempts to paint vaping as a gateway to smoking were completely and utterly unsupported by evidence.

- A study from CDC researchers claimed to show that vaping increased “intentions to smoke,” but this was woefully executed and the results were obviously caused by other, underlying factors.

- Despite never having made this point about smoking, the CDC then became unduly concerned that some evidence, largely from animal studies, suggests nicotine may negatively affect teen brain development.

- The CDC then completely removed itself from reality and began claiming that since e-cigs are classed as a “tobacco product” in a strictly legal sense (in the US), data showing rising vaping and falling smoking can be dismissed as showing “no change in overall tobacco use.”

- The CDC has never acknowledged that vaping is safer than smoking. Given the public confusion about the risks, this is seriously and dangerously negligent.

The Foundational Falsehood: Past 30-Day Use is Not “Current Use”

This is a point we’ve made every single year the data is released, and in many ways it completely underpins the whole deceptive approach the CDC has taken to vaping. In the National Youth Tobacco Survey, “current use” of e-cigarettes is classed as use on one of the previous 30 days. In other words, a teen who has tried vaping once – even just a couple of puffs – is a “current user” by the CDC’s definition, if those couple of puffs happened to be in the month before the survey.

Even from that example, it’s clear that this definition will capture plenty of youth who are just trying vaping out in addition to the genuine current users (who vape every day or every week, say). With cigarettes, it’s more reasonable to assume that past-month smokers are also regular smokers (which is why the survey question is set up this way), but for vaping it isn’t so simple. One study looked at youth specifically and found that while 18 % had vaped in the past month, just 2 % used them weekly or daily. Another study looking at adult use showed that the same basic conclusion carries over: almost all past-month vaping (particularly among never-smokers) was actually on five or fewer days out of the whole month.

So calling past-month vapers “current users” is misleading. If only the CDC had asked a different, more informative question, such as “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes?”

Then we wouldn’t have to depend on the ham-fisted “past 30 day user” definition, or at least we’d have more information about what the CDC actually found in its studies. We could even provide clear evidence that the “past 30 day use” definition is misleading for the specific data set we’re talking about.

What do you mean that’s exactly the question the CDC asked in the 2014 and 2015 surveys? You definitely wouldn’t have thought that was the case, because they certainly don’t report the answers to that question in their main analysis. You have to go to the trouble of downloading the raw data for 2014 (which is the latest available), to get the answers to the question. And it’s interesting, to say the least.

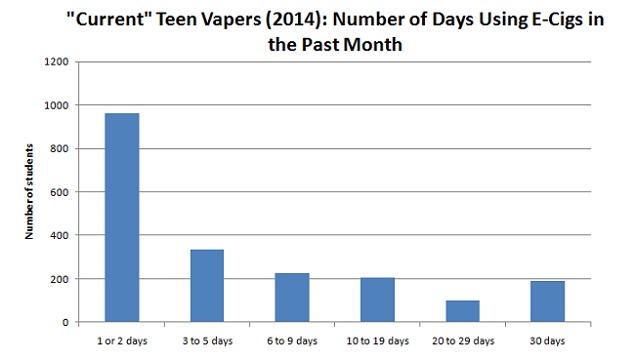

For the whole sample (including the smokers) for 2014, only around 36 percent of those who’d vaped in the past 30 days had done so more than five times in the month. This is the overall picture:

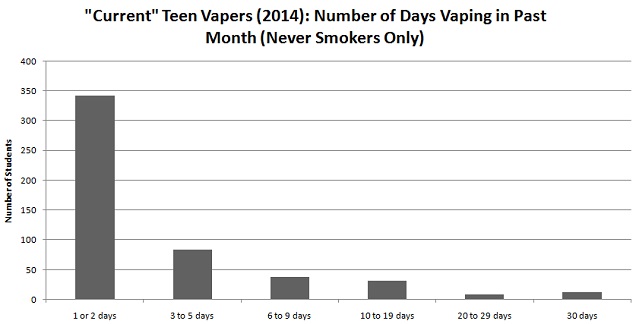

You can easily see that at least half (but probably a majority) of those “current vapers” aren’t currently vaping in the way the term implies. For the never-smokers (the ones public health is most concerned about), the situation is even more extreme. Only 18 percent of the never-smokers classed as “current users” had vaped more than 5 days in the past month. Out of all never-smokers, only 0.55 percent had vaped more than 5 days out of the past 30. The data looks like this:

Again, the picture is clear. A full two-thirds of the never-smokers who’d vaped in the past 30 days had only done so once or twice.

Of course, I’d love to be able to do the same thing for the 2015 data, but it isn’t available yet. And this is really the most serious issue. The findings are disseminated before even this basic point can be confirmed. Journalists pump out headlines and the results settle deep into the public conscious – doomed to endless repetition by journalists, researchers, various anti-vaping groups and politicians – before we can even make a firm statement about how often the teens vaped. The teens who vape once in the month before the survey will be “current” vapers forever in the eyes of most people who read about these results.

Now for the most troubling question: why does the CDC not present this analysis alongside the rest of the results? For anybody who’s been following the CDC’s disastrous approach to vaping, the answer is obvious. This is not a serious attempt to inform the country about the state of e-cigarette use among youth. If it was, there is no discernible reason whatsoever that they wouldn’t report the responses to that question in the main analysis. We’re only in the first section of this article, and it’s already abundantly and unavoidably clear that the communications on this issue from the CDC are purposefully misleading.

That’s harsh, I know, but I can’t see any other way to explain it. This is what the CDC has done:

- Define “current use” – a term most people would interpret as “ongoing regular use” – to mean “use at least once in the past 30 days.”

- Ask students “how many days of the past 30 have you vaped?” (or prior to 2014, not even bothered to ask for a number of days)

- Receive answers with numbers ranging from 0 to 30. The majority of responses are from 0 to 5.

- Split the responses into “0” and “1 or more,” watching as the actual regular users are swept up into a big, homogeneous group along with the casual experimenters.

- Report any of the responses in the “1 or more” group as “current users,” without justifying the decision to combine the responses, or dwelling too much on your tenuous definition of “current user” in your press release.

- Don’t report the actual frequency of use in the full write up of the results.

- Proceed to make a bunch of seemingly-scary statements to the media about the “epidemic” of teen vaping.

- Release the full data set – with the actually useful answers to the question you asked – a few months later, when all the interest has died down and the headlines have sunk into the public consciousness.

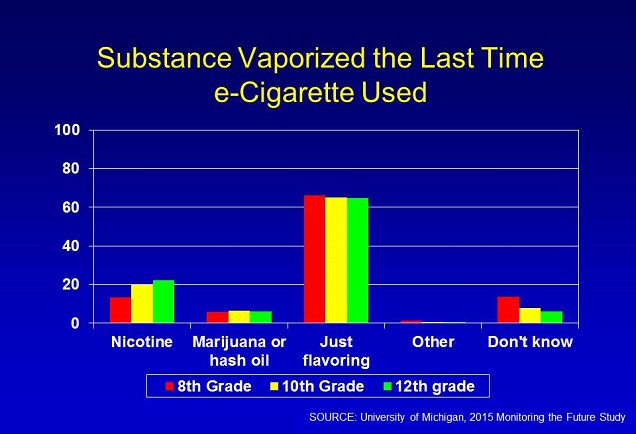

If that’s not intentionally misleading I don’t know what is. And this isn’t even the end of it. There is an additional question the CDC has never even asked: did you use a nicotine-containing e-liquid, or a non-nicotine one?

Although the CDC clearly doesn’t think this is important enough to bother asking, the people who conducted the Monitoring the Future survey did ask the question. High school seniors were most likely to use nicotine, but only 22.2 percent knowingly vaped a nicotine liquid, and an extra 6.3 percent didn’t know what they vaped. So only 28.5 percent vaped nicotine, as an absolute maximum.

Overall, it’s clear that the CDC’s version of the youth vaping situation is so hopelessly distorted that the only way to get anything approaching genuinely accurate and informative results from it is to download the data for yourself and analyze it. Is this how you communicate scientific results to the public? Well, it is if you have a message you want to get across, regardless of whether message is contradicted by the facts.

“E-Cigarettes Are a Gateway to Smoking”

Early on in the National Youth Tobacco Surveys which addressed vaping (back when they didn’t even ask how many days the “current vapers” vaped on), the core goal from the CDC’s communications was to paint vaping as a gateway to smoking.

CDC director Tom Frieden said, when the 2012 results were released:

Many teens who start with e-cigarettes may be condemned to struggling with a lifelong addiction to nicotine and conventional cigarettes.

Well, that sounds serious! So how did they find this out?

They didn’t. Tom Frieden, in that quote, is basically just making stuff up. The big problem is that the survey didn’t have the capability to determine whether vaping was a gateway to smoking. Even though it’s more complicated than this, to show e-cigs are a gateway to smoking you need to at least know which came first: the smoking or the vaping.

All the press releases making this argument actually presented from the surveys were the rising number of vapers, and the number who report vaping despite never smoking. It doesn’t take much consideration to realize that these two points don’t add up to “teens are starting out with vaping and then progressing to regular smoking.” They’re used to create the impression that this is what’s happening, but really they don’t mean much at all.

The technical problem is that the survey is “cross-sectional.” This means it takes information at a single point in time, and so it’s inherently incapable of saying one thing causes another. If they’d have found out that teens vaped first, and then (ideally after following-up with them a year or so later) these teens went on to regular smoking, it would be more convincing. But this is still too simple: would the teens have just started smoking otherwise if e-cigs weren’t available? Did they even become addicted to vaping?

The problems with what the CDC means when it says “current vaper” have a role to play here too, since we have good reason to assume that the vast majority of those who try vaping (and particularly the never-smokers) aren’t even addicted to nicotine. Even worse, in these first surveys to address vaping, the focus in the press releases was very much on the number that had ever tried vaping, rather than the “current” users. Obviously this will capture even more experimenters – those just trying vaping out with little interest in continuing.

Despite this, Tom Frieden thought it was perfectly fine to leap to the gateway conclusion anyway. While it did gain a bit of traction in the media at the time, it’s safe to say this conclusion was widely criticized by scientists, and the CDC moved away from gateway-like claims in the coming years. (Well, a little…)

However, this isn’t about what’s scientifically valid, it’s about advancing a viewpoint. It’s about painting vaping as some looming threat to society, even if the data doesn’t support it. And as anti-pot activists learned a long time ago, the mythical gateway effect is a very valuable tool for debates like this: if the thing you’re attacking probably isn’t that dangerous, you can pretend it leads to something that is. So, as Carl V. Phillips put it in his blog post, they “refined their lies” for the next approach.

“E-Cigarettes Increase Intentions to Smoke”

The trick was to talk about “intentions” to smoke. Their press release reported that:

Youth who had never smoked conventional cigarettes but who used e-cigarettes were almost twice as likely to have intentions* to smoke conventional cigarettes as those who had never used e-cigarettes.

First, note the * (leading to a footnote) beside the word “intentions.” This is because there is something wrong with their usage of the term, but they want to maximize impact without getting bogged down in all of the details that show just how much they’re stretching reality (why am I getting déjà vu?).

So how did they do this? The full paper makes for quite amusing reading after seeing the press release. They’re mainly focusing on the never smokers who tried vaping (the potential gateway cases), which means they have to explicitly state just how pathetic those numbers are. From 2011 to 2013, only 0.9 percent of never smokers had ever tried vaping, even once. For “current” use, the figure is a thoroughly pathetic 0.3 percent. This is the epidemic we’re supposed to be so scared of. Shockingly, they left these numbers out of the press release.

By comparing the never smokers who tried vaping with the ones who didn’t on a measure claiming to capture “intentions* to smoke,” they arrived at their intended conclusion, that vaping is a gateway to smoking associated with increased intentions to smoke.

So, about that * beside intentions. They didn’t want to draw attention to what they actually did for good reason. Let’s play the role of a teen responding to these questions.

First, they ask “Do you think you will smoke a cigarette in the next year?”

Definitely not, we respond, smoking is bad for you and we don’t have any reason to do it.

Then they ask, “If one of your best friends were to offer you a cigarette, would you smoke it?”

Well, we want to say no, but as a teen, we’re fairly concerned about fitting in. If our best friend offered us a cigarette, although we don’t really want to smoke, there is a chance we’d give it a try to avoid looking like a dork. Maybe we’re a little bit curious about what it would be like, too. So, being realistic about the whole thing, we reduce our level of certainty and just say “probably not.”

Congratulations, you now intend* to smoke. This is not a joke. That is literally how the study worked. As Brad Rodu called his blog post on the study, “In the CDC-FDA E-Cigarette Study, ‘Probably Not’ Is the New ‘Yes.’”

Carl V. Phillips hit on the key issue with this:

Any kid who is sufficiently familiar with reality, and not just dutifully echoing the “just say no” propaganda they are fed, would avoid responding “definitely not” to these questions or most any other questions about what the future holds. Geez, I would like to think that our high-school students are reality-based enough to know that there is always some nonzero possibility of such things occurring, making that “definitely” declaration almost always wrong.

But, as if that wasn’t bad enough, there is another key point about these youth with the increased intentions* to smoke. You’re comparing a group of never-smoking teens who’ve never even done anything remotely like smoking with the tiny proportion of them who actually have done something fairly similar to smoking.

Should we be surprised that they’re less likely to say they definitely won’t smoke? Of course not. I’d have bet money that they’d even be more likely to actually smoke than the ones who’ve never even vaped. The decision to vape – in itself – shows a bigger interest in smoking. Some underlying factors are leading these youths to try vaping while the others don’t, and it’s probably those same factors that make them less completely and utterly opposed to the prospect of ever smoking.

Yet again, this whole exercise comes off as little more than a weak excuse to contort a “gateway” conclusion out of some data incapable of supporting it.

“Nicotine Causes Brain Damage in Teens (But We Weren’t Worried About it Until They Started Vaping)”

The gateway claims and proto-gateway claims started to fizzle out a bit after that dreadful study. But the CDC realized that they don’t need a gateway after all. From around 2014 onwards, there was a new mantra at the ideologically blinded CDC Office on Smoking and Health:

Nicotine use can have adverse effects on adolescent brain development; therefore, nicotine use by youths in any form (whether combustible, smokeless, or electronic) is unsafe.

So instead of trying to show that e-cigarettes, despite not being dangerous on their own, would lead to something dangerous, the CDC changed tack and claimed that anything containing nicotine was dangerous. Why fabricate a gateway to something harmful when you can just massively over-exaggerate potential harm from the first substance?

The question is: does nicotine use have adverse effects on brain development in teens? The citation provided for the statement leads to the Surgeon General’s “50 Years of Progress” report (page 150 of the PDF). The evidence consists of animal studies and little else. As Michael Siegel comments in a blog post discussing this claim, “it is not clear whether one can extrapolate from animal models to humans.” He also points out that the human studies potentially providing support for the claim involve smokers, who get larger doses of nicotine and more frequently than most teen vapers, and especially never-smoking teens who’ve tried vaping.

Michael Siegel sums it up like this:

It is unlikely that the sporadic exposure to the low levels of nicotine delivered by e-cigarettes is sufficient to cause serious brain damage.

But even if it’s true that nicotine exposure from vaping during adolescence risks harm to the developing brain, we still can’t make a blanket statement declaring vaping to be a bad thing for teens. You know what else contains nicotine? Cigarettes. The only difference is that cigarettes contain so many things that cause harm that nicotine is barely ever implicated as a serious threat, and the whole issue of affecting adolescent brain development was (oddly enough) barely ever mentioned until vaping came on the scene.

So since it’s overwhelmingly the teens who’d otherwise be smoking that vape regularly, does the less serious danger from nicotine mean vaping is a bad thing for teens, on the whole? For most, the choice is between something definitely really bad and something possibly a little bit bad. The small number of never-smokers who vape often enough to potentially suffer these negative effects on the brain – or, more accurately, the even smaller number who use nicotine when they vape – pales in comparison to the large number of smoker teens switching to vaping or reducing the amount they smoke by vaping. The net effect is almost certainly positive.

But why would the CDC care about that?

“Overall Youth Tobacco Use Has Not Declined”

And finally, after a catalogue of awful arguments, misinterpreted research and a continuing blind refusal to acknowledge the benefits of switching to vaping for current smokers, we arrive at the latest tactic employed in the CDC’s misguided war against vaping. This was used in 2015 and this year, and is so idiotic it basically debunks itself. The argument is that, because e-cigarettes are a “tobacco product,” despite the declines in cigarette smoking, cigar smoking and pipe smoking, rising vaping means there has been “no decline in overall youth tobacco use since 2011.” Or even, vaping has “offset” declines in traditional tobacco product use.

What’s the problem? All together now: e-cigarettes don’t contain tobacco! While it’s true that if you use the very stifled, legal definition of “tobacco product” in the U.S., e-cigarettes qualify as a tobacco product (and have been deemed as such), this definition is completely and utterly useless outside of the legal, regulatory context it was intended for. The fact that a product meets the legal definition of tobacco product tells you nothing about its risks.

The deception is all the more inexcusable because, on numerous occasions, the CDC says “no decline occurred in tobacco use overall during 2011–2015” (my emphasis), or something equivalent to it. Saying “tobacco product use” would have been misleading on its own (though technically true in a meaninglessly specialized context), but classing e-cigarette use as “tobacco use” is a disturbingly brazen lie. You could say “nicotine use,” if you liked, but since you didn’t bother to ask if they vaped with nicotine or not, that would hardly be much better.

There has been a lot written about this latest ridiculous tactic, but the best (and most comprehensive) is undoubtedly risk communication expert Peter M. Sandman’s post on the 2014 survey and accompanying press release, entitled “A Promising Candidate for Most Dangerously Dishonest Public Health News Release of the Year.” It’s incredibly long, but well worth it if you want a look at how incredibly biased the CDC clearly is on this issue.

When discussing the tactic of calling vaping “tobacco product use,” Sandman offers this as an illustration of what is so monumentally and dangerously wrong with it:

Consider these comparisons:

- Imagine that teenage pregnancy was down and oral sex was up, and the U.S. government stressed that there was no change in overall teen sexuality and all sexual activity has risks.

- Imagine that sales of energy-wasting appliances were down and sales of energy-saving appliances were up, and the U.S. government pointed out that overall appliance sales were flat and all appliances use energy.

- Imagine that motorcycle riding without helmets was down and motorcycle riding with helmets was up, and a U.S. government report on the trend focused on no change in overall motorcycle riding.

- Imagine that gun battles were down and fisticuffs were up, and the U.S. government stayed steadfastly fixated on no change in overall violent behavior.

If it’s hard to come up with a comparison that isn’t laughable, maybe that’s because the failure to distinguish between smoking risk and vaping risk is itself so laughable. At least it would be laughable if it weren’t deadly.

Honestly, nothing else needs to be said on this latest CDC anti-vaping strategy. It’s dumber than the gateway argument, and that is really saying something. This is bottom of the barrel idiocy.

What the Hell is Wrong With You, CDC?

The reason this post is so long is because, with the regular, ridiculous assaults on vaping from the CDC, it’s easy to forget that we’re talking about an organization that is supposed to be respected and trusted. While in the UK, respected organizations are following the evidence and backing vaping as a safer alternative to smoking and a way for smokers to quit, the CDC is blatantly ignoring the evidence, pathetically refusing to acknowledge the potential for massive benefits from e-cigarettes and hiding behind a collection of deceptive mantras instead of taking an honest, well-considered approach to the issue.

The only conclusion that can be drawn is that the CDC Office on Smoking and Health is staffed by a bunch of prohibitionist luddites, who present the results of research into e-cigarettes in a purposefully misleading fashion and who cannot be swayed from their pre-determined position, no matter what the evidence says. They are behaving exactly like anti-smoking/anti-vaping activists, but they are supposed to be a respected governmental agency.

The problem is best illustrated by one key point: they have never clearly stated that e-cigarettes are safer than cigarettes. Even Stanton Glantz admits that. Tom Frieden may have admitted that they're less toxic (“stick to stick”) when pressed, but there has been nothing from the CDC as a whole even approaching the sort of unambiguous statements public health groups in the UK have been making. And since a depressingly large percentage of the public believe vaping and smoking pose the same risks, the lack of a clear statement from the nation’s foremost public health agency on this important issue is negligent and dangerous.

Does anybody at the CDC care if a smoker would try to switch to vaping, but doesn’t because he believes there isn’t much difference in the risk anyway? What if that person continues to smoke and eventually dies as a result? Do they care that their lack of comment – or even worse, the deceptive things they’ve actually said – could make this consequence more likely?

Because they should care, about both adult smokers and teen smokers who may be considering switching to vaping. They should rise above their inherent, instinctive negative reaction to e-cigarettes and stick with what the evidence tells us so far. By refusing to do this, they are showing themselves to be unable to make recommendations on this issue in the best interests of the nation. Smoking-related diseases continue to kill thousands upon thousands of smokers every single year, and there is a lot of misunderstanding of the relative risks of vaping and smoking, but they're too busy conjuring up new fears and misinterpreting research to paint vaping in a negative light. Their (understandable) desire to protect the nation's youth has led them to an almost callous disregard for people unable to quit smoking any other way.