A new study has demonstrated that e-cigarettes appear to reduce the ability of mice's lungs to fight off bacteria and viruses, a finding which has been reported as “E-cigarettes increase the risk of flu and pneumonia.” The authors state, based on their findings, that “E-cig exposure is not a safe alternative to smoking,” muddying the water between “safer” (as in much better than smoking, or reduced harm) and “safe” (as in 100 percent safe, vape all you want and you’ll have no increased risk of any health problems whatsoever). While e-cigs being 100 percent safe would be great, it’s hardly a requirement: if they’re safer than cigarettes – even if it was just 50 percent safer, rather than around 99 percent safer as current evidence indicates – then they still hold the potential to save countless lives.

So does this study cast doubt on e-cigs being safer than cigarettes? Not at all. Is it free from methodological issues? Definitely not; unless you happen to expose yourself to 1,080 puffs per day like the poor mice in this study were.

Summary

- Researchers looked at how e-cig vapor inhalation affects the clearance of bacterial and viral infections from the lungs, in both a live mouse model and using extracted cells.

- The e-cig group of mice was exposed to 1,080 puffs per day, with the cartridges only being changed after they’d been used for an average of 1,260 puffs – much, much longer than a carto’s lifespan.

- The e-cig exposed mice showed evidence of respiratory irritation, and their lungs were less effective at dealing with pneumonia and the flu than in non-vapor-exposed mice.

- Dr. Michael Siegel points out that aspirin also impairs the immune response to pneumonia, and so this finding alone doesn’t necessarily indicate danger from vaping.

- The authors conclude that e-cigs are not a safe alternative to smoking, despite the fact that e-cigs only aim to be safer than smoking, not 100 percent safe.

What They Did – Investigating the Effect of E-Cigs on the Immune System

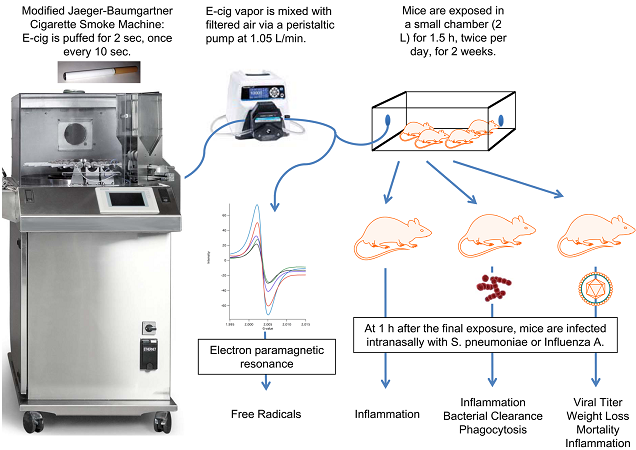

The basic aim of the study (available in full for free) was to look at the impact inhalation of e-cig vapor has on lung inflammation and clearance of bacterial and viral infections. Half of the mice were exposed to e-cig vapor (in a 2 liter chamber) while half breathed normal air, and then they were infected with either streptococcal pneumonia or influenza (the flu) to see how their responses differed. Some of the mice also had macrophages removed – these are a form of white blood cells that remove damaged or dead cells, like mini vacuum cleaners – and grown in dishes before being exposed to the infections to see how they responded.

The researchers point out the role of free radicals in oxidative damage, inflammation and “programmed cell death” (apoptosis), which spurs the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In line with this, they also measured the levels of free radicals in e-cigarette vapor.

Excessive E-Cig Exposure and Dry Puffs – Time to Feel Bad for the Mice

So how were the mice exposed? Excessively and stupidly, to put it bluntly. The researchers used a menthol 18 mg/ml Njoy e-cigarette (they also used a standard tobacco one with some mice to make sure the results were consistent), which was puffed every ten seconds for an hour and a half, twice a day. This represents 1,080 puffs per day, which went on for two whole weeks. Of course, human vapers only have around 200 to 300 puffs (give or take) per day, and we’re just a little bit bigger than mice. The E-Cigarette Industry Trade Association puts the exposure at around 2,000 times that of a human vaper, but there are problems with this estimate because the mice were simply placed in a chamber containing the vapor (so wouldn’t inhale it directly like a vaper would).

However, they do raise another crucial point. The smoking machine used was loaded with six fully charged batteries, which were rotated each puff so each e-cig was puffed once per minute. This means that each e-cig was puffed 180 times per day, but the researchers state that “E-cig cartridges were replaced each week” (our italics). Have you ever used an e-cig cartridge that you can puff 1,260 times before replacing? No, because it never happens. They say the replacement time was highly variable, based on when the machine detected a decrease in vapor output, but since most cartridges would last about a day under these circumstances, the method leaves a lot to be desired. The vapor production may drop eventually, but not before you lose flavor and experience dry hit after dry hit. Had this been detected when it should have been, would the researchers have still said cartridges were only replaced once per week? You would assume this would be an average, in which case it’s horrendously wrong.

Additionally, plenty of existing evidence indicates that the levels of things like formaldehyde increase dramatically in dry puff conditions. The real question is: for how many of the absurd number of puffs per day were the cartridges running on just a slither of e-liquid and producing un-vape-able dry hits? We don’t know, but probably a lot of them. The researchers did find that cotinine levels (a metabolite of nicotine) in the mice reached 267 ng/ml, though, which is lower than that seen in vapers. This indicates that the nicotine exposure levels were fair (even a little low), but is that because many of the puffs were of near-empty cartridges, because the mice only inhaled a fraction of the vapor produced, or both? Again, we don’t know.

What They Found – E-Cig Vapor Increases Oxidative Stress and Reduces Immune Response

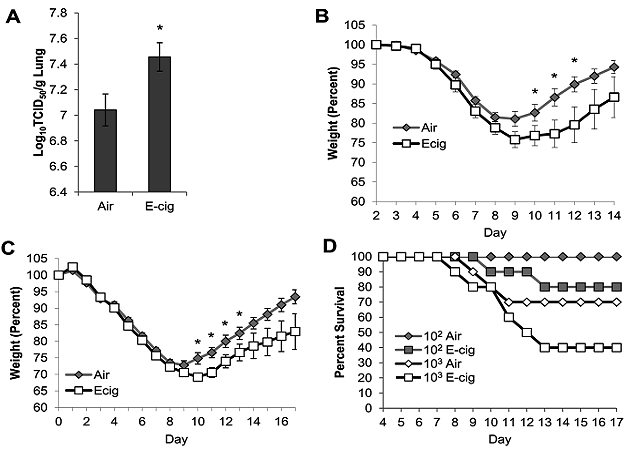

The researchers found that e-cigarettes contain 7 × 10^11 free radicals per puff (a 7 with eleven 0s after it) compared to around 10^14 per puff in cigarettes – this means e-cigs contain about 140 times less free radicals than cigarettes.

The mice exposed to e-cigarette vapor showed significantly increased levels of oxidative stress, and the number of macrophages present was 58 percent higher in comparison to the air-breathing mice – indicating an increased need to remove dead or damaged cells. This is a sign of respiratory irritation, which has been seen in other studies, and Dr. Michael Siegel points out that it isn’t clear whether it would translate into clinically meaningful lung problems.

When they were infected with pneumonia and later examined, the e-cigarette-inhaling mice had higher levels of bacteria in their lungs. When macrophages from vapor-exposed mice were extracted and grown in dishes before being infected, they were less able to deal with the infection than the non-exposed mice’s cells. The results for the flu were similar – levels of the virus were higher after infection, and two of the ten e-cig exposed mice died, compared to none of the air-exposed group. They’d also lost more weight 10 to 12 days after exposure, which the authors took as evidence of more severe illness, despite the fact that nicotine alone also has this effect. When they were infected with a larger dose of the flu virus, 60 percent of the e-cig mice died compared to 30 percent of the air-exposed mice.

It’s worth noting that there was no cigarette exposed group, and so there’s nothing relevant to directly compare e-cig exposure to (despite claims made in the study, vapers are almost all smokers or ex-smokers, so a comparison with cigarettes is crucial). Also, the most obvious issue is that this research was conducted in mice, and humans are not mice. It’s still useful (which is why such tests are conducted), but it’s far from conclusive that the same thing will be observed in humans, or that they translate to real-world increases in risk.

This is a particular issue, since Michael Siegel also points to evidence of the same effect occurring for pneumonia after aspirin exposure, but it would be ridiculous to make statements like “aspirin increases the risk of pneumonia.” Additionally, existing evidence shows that switching to e-cigarettes leads to improvements in condition for asthmatic smokers – a positive effect on an obstructive airway disease.

Conclusion – Vaping Isn’t Completely Safe, but It Doesn’t Have to Be

There are obviously several serious issues with making blanket “e-cigs impair immune function” statements based on this piece of research alone: it was conducted in mice using a method that’s highly unlikely to be representative of human use (likely increasing the levels of dangerous chemicals in the vapor) and the reported findings are not necessarily clinically significant. That said, it is clear from studies like this that e-cigs aren’t completely and utterly safe (the finding can’t be wholly ignored based on these issues alone), but saying that inhaling something that isn’t air and contains (albeit very small amounts of) harmful chemicals is 100 percent safe would be pretty stupid.

The core point – and one emphatically backed by the free radical levels found in this research – is that vaping is safer than smoking, which it almost certainly is. Put it this way: would you rather (maybe) get the flu a little more often or drastically increase your risk of cancer? I’ll take a possible small decrease in my immune function over a set of tumors any day.