The problem with a lot of the research on youth e-cigarette use is that the studies dance around the issue they’re designed to address: are non-smoking youths picking up nicotine use through vaping and progressing to regular smoking? That’s the core of the gateway hypothesis, but more often than not we merely end up with studies that show that small numbers of non-smoking teenagers have tried e-cigarettes at least once, with no indication of regular use other than the fact they’d vaped in the month prior to the study. This is obviously next-to-useless for establishing a gateway to tobacco use in anything but hypothetical terms. A new study (full text available for free) actually asks the questions that need to be asked, and (surprise, surprise) found no evidence of a gateway effect from e-cigarettes.

What They Did – Asking About First Use and Current Use of Nicotine Products

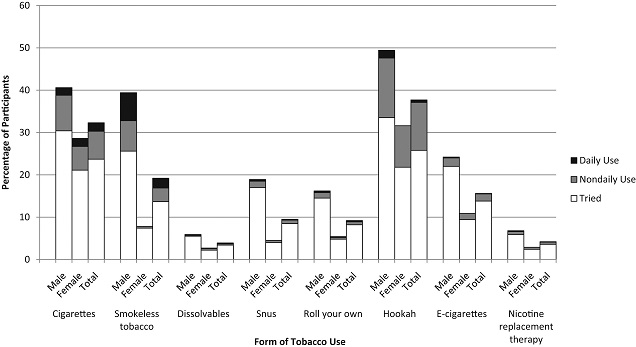

The researchers recruited 1,304 college students (on psychology and speech courses – mostly white and female) from 2012 to 2013 (in the academic year) to complete an online survey. The questions covered their first use and current use of combustible cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, snus, hookah, dissolvable tobacco, e-cigarettes or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). However, not many of the participants had tried e-cigs, snus or dissolvable tobacco, so they were all lumped together for the analyses under the label of “emerging tobacco products.” For those who’d used a product, they asked whether they’d tried it once, still used it occasionally or whether they were daily users.

What They Found – E-Cigarettes Only Very Rarely Lead to Cigarette Smoking

Almost half of all the participants had ever tried one of the products under consideration, and out of these individuals, hookah was the most-commonly tried product, followed by cigarettes, emerging tobacco products and smokeless tobacco. For their first-tried product, most (50.6 percent) started with cigarettes, with smaller amounts trying hookahs, smokeless tobacco, and emerging tobacco products (9.2 percent), in that order.

From the whole sample, only 4.5 percent (59 individuals) had tried emerging tobacco products before anything else, and 78 percent (46 individuals) of those had tried e-cigarettes first. Only 3.2 percent of the sample were daily or non-daily vapers, compared to 8.6 percent who were daily or non-daily smokers. Of course, e-cigarettes have increased in popularity since 2012-2013, so the current numbers are likely to be bigger than this. However, recent youth vaping data has roundly ignored the crucial question of daily or even regular use, so we still don’t have much to go on.

So what happened with those 46 people who’d tried e-cigarettes before any other nicotine-containing products? Not that much. Only two of them were still using e-cigarettes (occasionally) at the time of the study (according to the data tables: the discussion section says this is only one individual), and out of first users for all emerging tobacco products (also including snus and dissolvables), only one became a daily user of any tobacco product (cigarettes, in this case), and two became occasional users. This means just 5.1 percent of those who started with any emerging tobacco product were current smokers, either daily or occasionally, with another 5.1 percent (3 individuals) occasionally using smokeless tobacco. The biggest current use by far was occasional use of hookah, reported by 23.7 percent (14 individuals) of those who first tried an emerging tobacco product. Counting this along with combustible tobacco use, 28.8 percent of those who started on an emerging tobacco product were currently smoking in some form.

Comparisons with other first-tried products are generally favorable. For tobacco cigarettes, 18.4 percent of those who tried them first continued as occasional smokers at the time of the survey, and 6.1 percent went on to daily use, making 24.5 percent (80 individuals) of them current users in some form. Even for smokeless tobacco, 15.5 percent of those who tried it first went onto occasional smoking, with 3.1 percent smoking daily, for a total of 18.6 percent (18 individuals) becoming current smokers of some description. For smokeless tobacco, 16.5 percent of those who started out using it (16 individuals) continued as current daily users.

Is the Nicotine Gateway Hypothesis Complete Bull?

The most general form of the nicotine-related gateway hypothesis looks on shaky ground altogether, according to the basic findings and the subsequent analyses. The core idea is that trying nicotine in some specific form will make you more or less likely to try another type, and the main concern for anybody rational is combustible cigarettes. The analyses revealed that only sex was a significant predictor of current tobacco use, with men being about 50 percent more likely to use tobacco as women.

For use of multiple products vs. use of nothing, there were a couple of substance related differences: those who tried cigarettes first were around five times as likely as those who started on hookah to use multiple products, and were over three times as likely as those who started on emerging products. For people who first tried smokeless tobacco, they were over four times more likely to be users of multiple products than those who started on emerging products and over six times as likely to be doing so as people who started on hookahs.

Aside from cigarettes, the only gateway-like effects are potentially seen with smokeless tobacco, and even then only three people out of the 97 who first tried it went onto daily smoking. Granted, more occasionally smoked or used a hookah, but occasional smoking doesn’t seem like real issue. If anything, the main thing that predicted current smoking was starting out smoking, and the main thing that predicted current smokeless tobacco use was starting out on smokeless tobacco.

The alternative to the “gateway” idea is the considerably more sensible “common liability” model, which – instead of ascribing borderline-magical properties to specific substances – simply states that some people are more likely to try drugs (of all forms) or become addicted than others. They share some characteristics (whether genetic, environmental, psychological or all of the above) that influence their likelihood of trying something out. So the real question is, with very little in the way of evidence for the gateway idea, why bother with it at all?

Conclusion – Vaping Does Not Lead to Smoking

This study wasn’t perfect, admittedly. At the time these students were likely trying their first nicotine product, vaping wasn’t as popular as it is today, and those who tried e-cigs first probably had a couple of puffs on a cig-a-like. There’s a chance that future studies will find that starting out vaping really does make people more likely to take up smoking, but given how rare it is for studies to even attempt to answer the most important questions, this seems like the most reliable and relevant evidence to date.

And the study’s message is clear: trying e-cigarettes doesn’t lead people into smoking tobacco. Given that this would require switching from a pleasant, delicious-tasting habit to one that tastes like smoldering ass and is about 100 (if not more) times as dangerous, all for the exact same drug, it doesn’t exactly seem likely.