A new study claims to have found that watching e-cigarette ads featuring the act of vaping increases the urge to smoke for daily smokers and weakens intentions to continue abstaining for ex-smokers. Of course, a lot of necessary nuance is lost when the results are reported in the media, with Time claiming that the researchers found “watching advertisements showing vaping can increase the desire of current and former smokers to pick up a conventional cigarette.” The finding is destined to be used as a reason to come down harshly on e-cig companies advertising their products to interested smokers, but is the result really what it seems? As is depressingly often the case, even a cursory look at the data shows that the findings need to be interpreted with caution, and the implications really aren't as straightforward as Time implies.

Summary

- Researchers recruited 884 smokers and former smokers, and randomly assigned them to either view three e-cig adverts in full, to listen to audio from the ads only or to not hear or see any ads.

- They looked at smoking urges before and after the experiment, and also looked at self-rated ability to quit (or avoid relapse), attitudes towards abstinence and their intentions to quit or continue abstaining. They also asked whether participants smoked during the test.

- Urges to smoke for all groups (viewing, listening or neither) decreased relative to their baseline score after the ads, regardless of smoking status. For the daily smokers, those who viewed the ads had a higher urge after viewing (adjusted for their baseline urge) than those who listened to or didn’t see ads.

- Former smokers who’d seen the ads scored lower on intention to remain abstinent than those who’d only heard the ads or didn’t see/hear any ads, but their score was still five times higher than some-day or daily smokers’ comparable scores.

- When former smokers were split up according to how long they’d quit, the differences between viewing groups in their intention to remain abstinent disappeared.

- Daily smokers viewing the ad were more likely to smoke during the test than those listening to or not viewing ads, but this finding just missed out on statistical significance.

- Overall, the negative effects of e-cigarette ads observed were very minor, and are clearly outweighed by the benefits of encouraging smokers to quit.

What They Did – Showing Smokers and Ex-Smokers Vaping Ads

The researchers recruited 301 daily smokers, 272 some-day smokers and 311 former smokers (who’d quit for at least three months) to look at the effect of seeing vaping ads on the urge to smoke (the full text is paywalled), perceived ability to quit smoking (or continue abstaining), attitudes towards smoking abstinence and intentions to quit or continue abstaining. The basic aim can be summed up simply: seeing images of smoking increases desire to smoke, and since vaping looks like smoking, ads for e-cigarettes might have the same effect on smokers and ex-smokers.

To test this, the researchers found some e-cig ads, edited out any cigarette cues (so e-cig cues were the only thing tested), and produced two versions of each – one with visuals (of things like holding an e-cigarette and actually vaping) and one with visuals removed but the audio track still present (along with a displayed transcript of the dialogue). These were all ads for cigalikes (from Blu, Green Smoke, V2 and others), with the researchers planning a study on non-cigalikes for the future. The participants were randomly assigned to view either ads with visuals, audio-only ads or no advertisements (instead answering unrelated questions about media use).

The participants in either of the ad groups viewed three ads one after another. This is more than would realistically be seen consecutively (or in quick succession) either on TV or online (unless you were actively looking for vaping-related stuff), which is relevant because of something called ego depletion. Although it’s not quite this simple, it can be summarized as saying that willpower is a finite resource: every time you exercise self-control, doing so again becomes harder, and so on. So the smokers and ex-smokers in this study had three-rounds of temptation, each sapping away at the desire to avoid smoking or maintain abstinence.

What They Found – Smokers Seeing Vaping Cues Have “Increased Smoking Urges”

Click here for full size table.

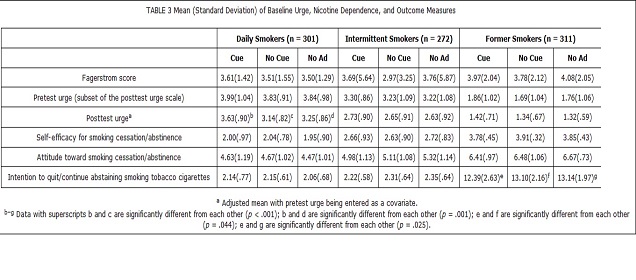

The participants’ urge to smoke was assessed using a five-point scale both before viewing the ads (or going through the control procedure) and afterwards. Daily smokers in each group had similar urge scores (from about 3.8 to 4) to each other at baseline, as did intermittent smokers (around 3.2 to 3.3) and former smokers (1.7 to around 1.85), although in all cases those in the full ad group had the biggest baseline urge. After viewing the ads, the score on urge to smoke actually decreased for all groups. As the authors point out, the decrease occurred even for those who didn’t view or listen to any ads, so there is obviously an effect related to going through the process causing a decrease in urges, even when no mention is made of smoking or vaping.

So where is the “increase in urge” to smoke from the headlines? For the daily smokers, those who watched the ad had higher post-test urge scores compared to those who either just listened to the ad or didn’t see or hear an ad, after adjusting for their baseline urges. Their (adjusted) urge score decreased from 3.99 to 3.63 (a 0.36-point reduction), compared to a decrease from 3.83 to 3.14 (a 0.69-point reduction) for the daily smokers who listened to the ad with the words written on-screen and a decrease from 3.84 to 3.25 (0.59-point reduction) for those who didn’t see or hear the ad.

Does this correspond to an “increase in urge” to smoke? Well, it’d be more informative to say “a smaller decrease in urge,” but it’s true that on average, after the test, those who viewed the e-cigarette ad reported higher smoking urges than the other groups of daily smokers. However, “increase in urge” would ordinarily suggest that their baseline urge actually increased after viewing the ads, which wasn't observed here, so it’s a little misleading in that sense. Of course, it makes sense that seeing somebody vaping would make smokers or ex-smokers think about having a cigarette, and you'd expect a small increase in urge, but the evidence for it here isn't particularly compelling.

For the some-day smokers and ex-smokers, their urges decreased after the test condition too, but there was also no significant difference between groups: seeing somebody vape was no more urge-inducing than listening to ads or answering questions about their media use.

Vaping Ads Cause “Decreased Intention to Abstain” in Former Smokers

Although baseline measurements are not available for these, there was no significant difference between viewing condition groups in perceived ability to quit, attitude towards quitting and intentions to quit for either the daily or some-day smokers. The only significant finding was for the former smokers who viewed the ad, for their intention to continue abstaining, and this is again only significant relative to the former smokers in other groups (either just listening or with no ad).

Specifically (noting that high scores are good in this instance), those who listened to the ads scored 13.1, those in the no-ad group scored 13.14 and those viewing the ad scored 12.39. In comparison, none of the groups of daily or some-day smokers scored more than 2.4.

And now comes the “ego depletion” issue. Is it surprising that ex-smokers – with memories of nicotine addiction still reasonably fresh – would be a little less resolute in their desire to remain abstinent after witnessing three consecutive ads glamorizing vaping? Not really. It may simply be an expected ego-depletion effect, and not a particularly strong one at that.

To the researchers’ credit, they realized that former smokers who’d recently quit might be more affected than those who’d quit a long time ago, and they performed an analysis with these groups separated to work out if this was the case. They found that the more recent quitters had greater urges to smoke overall (pre and post-test), and scored worse on self-rated ability to quit, had reduced intentions of abstinence and less favorable attitudes to abstinence.

For the core issue (does seeing vaping decrease intentions to remain abstinent?), the authors report, “No significant differences emerged across ad conditions for any of the outcome variables in either the recent former smoker or the long-term former smoker groups.” In other (less clumsy) words, when only recent quitters or only long-term quitters were examined, the different conditions (full, only audio or no ad) didn’t make a significant difference to the scores. The mean scores broadly followed the same pattern as when the groups were pooled together, but seeing vaping-related images no longer had a statistically significant effect.

How Many Smokers Lit Up During the Test?

Since the test was conducted online, the smokers may have smoked during the test. The authors found that, of the daily smokers, 35.7 percent of the full-ad group smoked during the test, compared to 21.6 percent of those in the audio-only and 22.5 percent of those in the no ad group. Hilariously (translation: depressingly), the authors report that “the difference in percent smoking was marginally significant,” but go on to quote a p-value of 0.054 – as in, a value higher than the standard cut-off of 0.05, which is more conventionally (translation: accurately) called not significant. This finding is obviously very close to significant (and the raw difference in percentages is notable), but to claim it is statistically significant (and without further explanation) is sloppy practice, to say the least.

For intermittent smokers, 9.7 percent of those viewing ads smoked during, 8.8 percent of those listening did and 6.1 percent of those not seeing or hearing ads smoked – this non-significant finding was correctly reported as not significant. No former smoker smoked during the experiment.

Conclusion – Another Sloppy Study with an Agenda

So Time’s reported “increased desire” to smoke for current and former smokers seeing a vaping ad really should have been, “a smaller reduction in desire to smoke” for the daily smokers, and “a slight reduction in intention to abstain” for former smokers, where the latter is likely explained through ego depletion and disappears when they’re grouped according to length of time since quitting. You'd obviously expect that vaping advertisements would increase the urge to smoke for smokers, but this study struggles to show even that.

However, even if we do accept the media reporting, it’s hardly a reason to ban vaping in ads – the benefit to the smokers who ads convince to quit is much bigger than the detriment of a slight increase in smoking urges (relative to not seeing an ad) for daily smokers and a minor decrease in intention to remain abstinent in former smokers. Switching to vaping almost definitely saves lives, while the latter two likely make no difference whatsoever.