If you want a constant stream of junk science on a topic, one thing you’ll need is some researchers willing to crank out a shoddy paper in support of your cause, ideally without putting too much work into it. For e-cigarettes, the junk science never seems to let up, and there are plenty of researchers wary enough of vaping to allow some apparent bias to creep into how they conduct and report the results of their studies. One recent example led to widespread declarations that “e-cigarettes don’t help people quit smoking,” but as soon as you take a look past the headline, you see that it wasn’t a study that could have possibly led to that conclusion – some researchers just examined Google search trends related to vaping.

The name on the study seemed familiar, Rebecca S. Williams. A little Google search later (which is apparently a highly scientific discipline) and the reason became clear: she isn’t new to this game. This is actually the third time her name has been attached to a laughable piece of anti-vaping junk science that required little more than browsing the internet. Let’s take a look at all three of them and enjoy a moment of silent appreciation of her contribution to the cause of criticizing vaping for any reason you can think of.

1 – Divining People’s Intentions Through Keyword Analysis

The newest study from Dr. Williams, Dr. John Ayers and others managed to drag “e-cigs are useless for quitting” headlines out of an analysis of search keywords. Seriously.

The e-cigarette industry, the media, and the vaping community have promoted the notion that e-cigarettes are an effective device for quitting smoking, yet what we're seeing is that there are very few people searching for information about that.

Although the researchers presented some findings that may be of use to some people – for example, the word “e-cigarette” is declining in usage and being replaced with “vaping” or related words – it’s safe to say the whole endeavor was a waste of even the minimal effort required. Plus, if you’re familiar with vaping and the evolution of the language used, the shift away from “e-cigarettes” is hardly surprising.

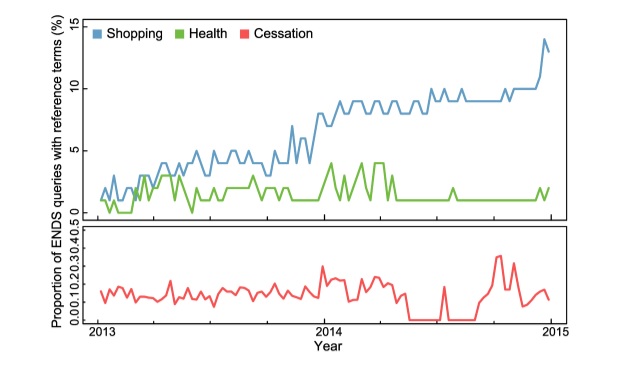

The attention the study received stemmed from a couple of results, with each making headlines separately about a month apart: only about 3 percent of searches related to vaping used terms that suggest concern about health risks (e.g. “e-cigarette risks”) and 0.3 percent or lower were clearly related to quitting smoking. The example they gave of this type of search is “do e-cigarettes help smokers quit?”

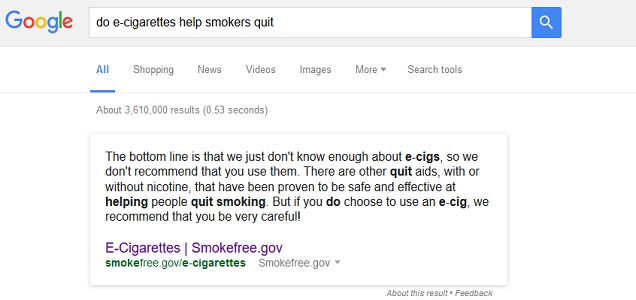

To see the catastrophic issue with this assumption: let’s just Google it. First, you’re presented with this:

And secondly, only three of the first 30 results actually provide anything resembling useful information on quitting smoking by vaping. Really, only the second result actually contained tips. There are a hell of a lot of “do e-cigs help you quit” news stories, but very little in the way of the sort of practical tips you probably want. Here’s a wild idea: maybe that’s why not many people bother searching for it.

The authors seem to imply that the searchers for “buy e-cigarettes” are about “shopping,” rather than quitting smoking. There are so many issues with this that it’s hard to know where to start. It seems they were unable to imagine that people might know what they want to do before they start searching for something. Vaping is a replacement for cigarettes. If you want to vape instead of smoke, you just try to vape when you would have smoked. You don’t need a special type of e-cigarette or anything in particular to do so, you just need to buy an e-cig and give it a go.

There are plenty of tips that can help along the way, but if you were interested in quitting smoking, you would hardly need to add “quit smoking” to the end of your search. It would be like searching for “decaffeinated coffee” but then inexplicably feeling the need to add “to quit caffeine.”

As Michael Siegel notes, the authors seem to think they can read the minds of the searchers based on the keywords that they choose. If they had that ability, I’m pretty sure they could get a better job than adding to the mountain of anti-vaping junk science: they could help law enforcement work out when someone was searching “buy knives” because they’re planning a murder rather than just planning on cutting up some vegetables.

2 – Kids Can Buy E-Cigarettes Online… If They Have Their Parents Driver’s License and Credit Card

This study led to claims that “teens can easily buy e-cigarettes online,” with three out of four attempted e-cigarette purchases being successful. The study did find that, but a couple of points undermine the result to the point of making it entirely meaningless.

Firstly, the study notes:

Youth buyers were recruited with a parent who gave written permission for his or her child to use the parent’s driver’s license to attempt to bypass age verification.

And secondly:

All purchases were made with credit cards issued for each youth buyer in his or her own name or his or her parent’s name. (emphasis mine)

So, “most teens can buy e-cigarettes online easily” should really read, “most teens with access to a parent’s driver’s license and credit card can buy e-cigarettes online easily.” Somehow, I don’t think that would have been quite as headline-friendly.

In fairness to the authors, a follow-up study did require youth to use their own cards and their own ID, and the results showed that very few vendors performed the checks necessary to confirm that the purchaser was old enough to vape. Why they didn’t just do this the first time around is anybody’s guess, but the fact that the concerns turned out to be justified in no way excuses the first, thoroughly absurd attempt to demonstrate it.

3 – Researchers Discover Vaping Conventions, Are Inexplicably Horrified

This is the most laughable and lowest-effort study of the bunch: it consists of Rebecca Williams learning about vaping conventions using Google and then prattling on about how public health doesn’t get invited to come along and throw cold water on the festivities.

She writes:

Vaping conventions promote e-cigarette use and social norms without public health having a voice to educate attendees about negative consequences of use.

Well who’d have thunk it? Next she’ll be bemoaning the fact that rock festivals don’t include a booth full of people yelling about how “loud music can damage your hearing” as Slayer blares out Raining Blood or how beer festivals don’t have a booth of busybodies warning everyone about liver disease. We’re trying to have fun!

She then goes on to suggest that since people vape at the conventions (the horror!), “Future research should focus on the effects of attending these conventions on attendees and on indoor air quality in vapor-filled convention rooms.”

And that study happened, too. The researchers came up with the startling revelation that rooms full of people vaping contain vapor, and all they had to do was sneak around and hide what they were doing while ignoring any potential ethical issues (as discussed by Carl V. Phillips and Clive Bates). They’re expecting their Nobel Prize any time now.

Want to Join the Crusade Against Harm Reduction? Get Your Laptop Out!

The primary lesson from Rebecca Williams and her colleagues’ forays into e-cigarette research is that you can accomplish a lot if you just have an internet connection and are capable (ish) of using Google. If you follow in her footsteps, you might just discover that the worrying (and apparently in no way whatsoever related to quitting smoking) trend of people searching for “buy e-cigarettes” is continuing! Egad! You might even find out that these “VapeCons” don’t display giant neon warning lights saying “These products are not approved as smoking cessation devices.” And if you do, journals and journalists will apparently be lining up to give you a platform from which to spout whatever nonsense suits your agenda.