Just when you thought the whole formaldehyde issue had been abused enough, utterly debunked by subsequent research and relegated to the slush-pile of over-stated risks of e-cigarettes, it turns out there’s more. The Center for Environmental Health (CEH) – a “health watchdog” dedicated to protecting “your children and family from toxic chemicals” – has announced that they’ve found “high levels” of cancer-causing chemicals in the majority of almost 100 e-cigarettes tested.

Their report, entitled “A Smoking Gun: Cancer Causing Chemicals in E-Cigarettes” covers the standard array of “think of the children” complaints about candy flavors, marketing to youth, warns about nicotine poisoning from e-liquids, claims e-cigs don’t help smokers quit and more. However, the “smoking gun” is apparently the finding that 50 out of 97 products contained high levels of either acetaldehyde or formaldehyde.

The Results at a Glance

- Researchers tested 15 disposables, 32 cigalikes and 50 refillable e-cigarettes, from 24 manufacturers.

- They claim the testing was conducted at realistic temperatures, but provide no information on the method other than that it was conducted by a reliable lab using a smoking machine.

- 50 of the 97 products contained levels of formaldehyde and/or acetaldehyde exceeding the California Prop 65 limit, which means they pose a risk of over 1 in 100,000 for getting cancer over a lifetime of exposure.

- Existing evidence, in combination with the Prop 65 limits, suggests that the highest results obtained in this study (473 times more than the limit for formaldehyde and 254 times more for acetaldehyde) must have been due to dry puffs.

- E-cigs do expose users to more of these chemicals than the Prop 65 limits in normal conditions, but still much less than cigarettes.

E-Cigarettes and Aldehydes: The Role of Dry Puffs

As most vapers will know, the production of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde and other similar chemicals by e-cigarette is heavily influenced by the settings used and how frequently you puff. If you apply too much power for a specific setup, the e-liquid in the wick can’t replenish quickly enough, it overheats and the PG degrades into formaldehyde, with a sharp spike in formaldehyde levels (which can increase by up to 200 times) after you pass a certain wattage threshold. The most famous example of this finding is the New England Journal of Medicine report, which found that when abused in this fashion, e-cigarettes can put out more formaldehyde than cigarettes.

The big problem is that these spikes in formaldehyde are accompanied by “dry puffs” – which taste so disgusting that it almost defies explanation. This issue was wonderfully demonstrated by a study from Dr. Farsalinos, who gave vapers devices to use at various wattages, and told them to identify the settings that lead to dry puffs. The vapers all identified the same specific settings of concern, and when the chemistry of the vapor was tested at these various settings, the spikes in formaldehyde came exactly at the points when users identified dry puffs, which nobody would realistically vape.

The upshot for researchers is that if you’re testing e-cigarette vapor, the settings and puffing protocol you use is absolutely vital information.

The Report – What They Did

Unusually for something purporting to be scientific testing, there is no real information provided about the method used to test the e-cigarettes. They tested 15 disposable, 32 cigalike and 50 refillable devices, but they don’t specify which classifications the “refillable” devices fall into, and if they were mods, they offer no information about the wattage and atomizer used. They do list brands – such as EverSmoke, NJOY, Vuse, Joyetech and Blu – but don’t provide any further information. They tested the products from 24 companies in total.

The report does point out that the New England Journal of Medicine study was criticized for using unrealistically high temperatures, and claims that they tested the devices at temperatures common for normal use. These temperatures weren’t stated, of course. They say they used a smoking machine for the testing, and it was conducted by a lab that has experience testing both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, but tell us little else about what they did. In a sentence, the information provided about the method can be summarized as “we tested some e-cigarettes, but we’re not telling you how.”

The main aim of the analysis was to look at how the levels of acetaldehyde and formaldehyde in e-cigarette vapor compares to the safety levels set under California’s Proposition 65 law.

What They Found – Some E-Cigs Expose Users to Unsafe Levels of Aldehydes

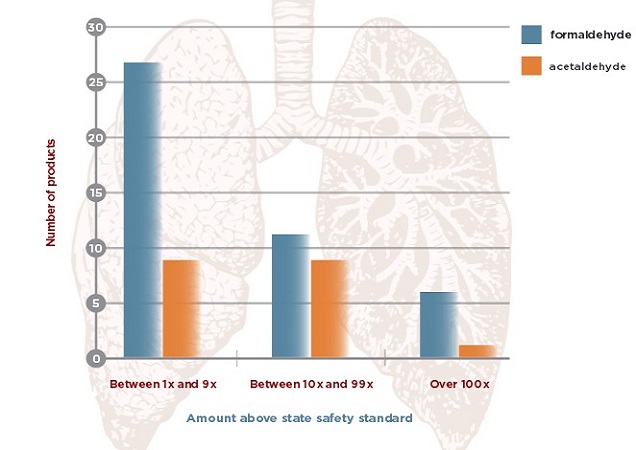

The results are presented as nebulously and poorly as the methods. This graph is pretty much it:

The text also explains that at least one product from 21 out of 24 companies expose users to hazardous amounts of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde or both. Of the 97 products, this equates to just 50 products, which is about 52 percent. They point out the highest levels found specifically: 473 times the safety limit for formaldehyde and 254 times the safety limit for acetaldehyde. They’re also apparently surprised that nicotine-free products can also produce these chemicals – which, as mentioned earlier, are due to PG and not nicotine – pointing out that one nicotine-free option had over 13 times the safety level for acetaldehyde and over 74 times the level for formaldehyde.

So, with no actual figures whatsoever, the content of these Proposition 65 limits become pretty crucial to interpreting the findings. The No Significant Risk Level – which is a daily intake level that would result in one extra case of cancer for 100,000 people exposed over a whole lifetime – for acetaldehyde is 90 μg per day (0.09 mg) and for formaldehyde is 40 μg per day (0.04 mg). A crucial methodological question – which, surprise surprise, goes unaddressed – is what they define as a day’s worth of vaping. Without that, it’s really quite difficult to work out what they found at all.

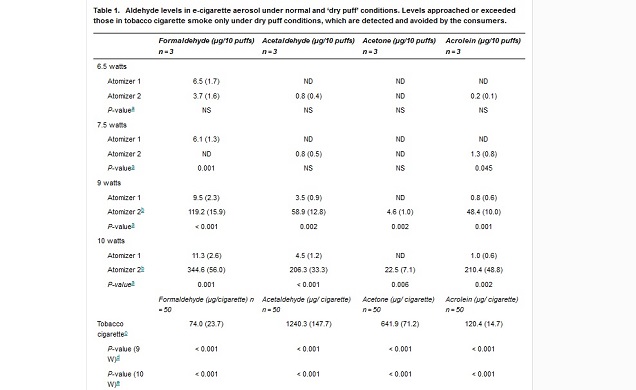

The highest, non-dry puff levels from Dr. Farsalinos’ study were 11.3 μg per 10 puffs for formaldehyde and 4.5 μg per 10 puffs for acetaldehyde. If we make the assumption of 300 puffs per day, this would be 339 μg of formaldehyde (8.5 times the prop 65 limit) and 135 μg of acetaldehyde (50 percent more than the prop 65 limit). To obtain the highest results from this report with 10-puff values from Dr. Farsalinos’ study, it would require over 16,700 puffs for formaldehyde and over 50,000 puffs for acetaldehyde. But if we use the highest dry puff values from Dr. Farsalinos’ study, it would take 549 puffs for formaldehyde and over 1,100 puffs for acetaldehyde. It’s clear that if they made any sort of reasonable estimate for a day’s vaping, dry puffs were almost definitely a factor in these results.

For cigarettes – a comparison not given in the CEH report – a single cigarette releases around 74 μg of formaldehyde and 1,240 μg of acetaldehyde. That means a pack-a-day smoker would exceed the Prop 65 limit for formaldehyde by a factor of 37 and for acetaldehyde by a factor of over 275. Even in whatever ridiculous situations these e-cigs were tested in, vapers would still be exposed to less than smokers for acetaldehyde, and only around 17 products out of 97 even stand a chance of exposing vapers to more formaldehyde than smokers.

The 1 to 9 times the Prop 65 limit column – which most e-cigs with detectable levels fell into – is roughly in line with existing evidence. For the larger quantities of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, dry puffs were almost certainly a factor. The fact that e-cigarettes do still exceed Prop 65 limits for these two chemicals even in normal situations would be concerning, if they weren’t a replacement for cigarettes.

The Rest of the Report – Typical Anti-Vaping Nonsense

The rest of the report is basically full of the standard anti-vaping nonsense we’ve all become wearily accustomed to. They claim e-cigs don’t help smokers quit, pointing out that a clinical trial found them to be only as effective as patches, but then in the next paragraph imply that patches do help smokers quit. They think “mods” is short for “modules.” They acknowledge the fact that vapor should really be called aerosol but still insist on calling it smoke. They say calling e-cigarettes healthier and cheaper than cigarettes is “deceptive” marketing. And – possibly the stupidest thing in the whole report – claim that a teaspoon (about 5 ml) of ordinary strength e-liquid has enough nicotine to kill an adult. This would be 90 mg for an 18 mg/ml e-liquid, way short of the 500 mg which is the lowest reliable estimate for the toxic dose of nicotine for adults.

Conclusion – No Smoking Gun

Overall, the report promises a lot and delivers nothing whatsoever. The sole purpose appears to be to support the legal action the CEH is pursuing against e-cigarette manufacturers for failing to warn customers about the cancer risk. They claim such warnings aren’t common, but in my experience they actually are: most vapers are used to seeing the Prop 65 warning on e-liquid bottles. In any case, for vapers, the results here are best ignored in favor of peer-reviewed research with methods and findings presented transparently, but even a rudimentary analysis shows that the real-world applicability of the more extreme results in the report is probably extremely limited.

If anyone from the CEH is interested in providing more information about the method to clear that up – you know, for the consumers you claim to be protecting – I’d love to hear it.