A new piece of research published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine has offered evidence destined to be used as a justification for spreading fear about the assumed risks of e-cigarettes. Although there is no evidence of any significant risk to e-cigarette users, the study has prompted headlines like “Are e-cigarettes luring teens into tobacco use?” and in-text comments such as “many people anecdotally believe that they are safer than traditional tobacco products”. To cause all of this fuss, you’d think the piece of research offered up some evidence that e-cigarettes are attracting significant numbers of non-smoking teens or that there is some evidence of harm from e-cigarettes, but sadly, this is far from true. In fact, the research – when you actually look at what they did and what they found out – is pretty inconsequential.

Summary

- Researchers aimed to determine whether young adults’ opinions on the safety of e-cigarettes, their potential as smoking cessation aids and their addictiveness impacted on whether or not they tried e-cigs over the course of a year.

- 1,379 non-vaping participants (69 percent non-smokers) were recruited, indicating the degree to which they agreed with the statements above (regarding safety, efficacy and addictiveness) and their smoking status. After a year, they were asked if they’d used an e-cig at all.

- 21.6 percent of smokers, 11.9 percent of former smokers and 2.9 percent of non-smokers used an e-cig at least once in the year after the first survey. Participants were more likely to vape if they believed e-cigs to be safe, effective for quitting smoking and less addictive than tobacco.

- The researchers express concern that the small amount of experimentation (by three in every 100 non-smokers) with e-cigs is a potential gateway to addiction, in spite of no evidence in favor of that conclusion, and that 11.9 percent of former smokers consumed nicotine again through e-cigarettes (although tobacco relapse rates are at around 80 percent).

- The Discussion section of the paper is rife with cherry-picked studies, omitted information and bizarre, unsupported claims like that e-cigs leading to congestive heart failure, undoubtedly contributing to outrageously misleading news reporting on the research.

What They Did – Does Opinion on E-Cigs Make Use More Likely?

The basic question the researchers set out to answer was whether or not the “beliefs” that e-cigarettes can help people quit smoking (which, incidentally, is supported by plenty of evidence), that e-cigarettes are safer than smoking (which is also supported by plenty of evidence) and that e-cigarettes are less addictive than cigarettes (guess what? There’s evidence to suggest that too) make it more likely that people will use them. Right off the bat, we’re assuming you’ll be able to work out the answer to this. If you think, say, bacon isn’t going to do any harm to you, you’ll obviously be more likely to eat it than somebody who thinks it’s going to give them cancer or make them obese. It’s just common sense.

To answer this question, the researchers used data from the Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort, which recruited an initial sample of 4,826 participants aged between 12 and 16 between 2000 and 2002, then surveyed them throughout 2007 onwards. For this piece of research, they took their sample from the surveys conducted between October 2010 and March 2011, and the follow-up surveys issued to the same participants a year later. This resulted in a sample of 1,379 participants with an average age of around 24 (so to clarify, definitely not teens) who had never used e-cigarettes at the time of the baseline 2010-2011 surveys (69 percent were non-smokers at the time of the first survey).

The survey included the statements, “using e-cigarettes can help people quit smoking,” “using e-cigarettes is less harmful to the health of the user than smoking cigarettes” and “e-cigarettes are less addictive than cigarettes,” and respondents had to indicate how much they agreed with these statements on a five-point scale between “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” If the respondent hadn’t smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and hadn’t smoked in the past 30 days they were classed as a non-smoker, if they’d had over 100 cigarettes but not in the past month, they were classed as a former smoker, and if they’d had over 100 cigarettes and smoked at least one day in the past month, they were classed as a current smoker. During the follow-up survey, they were asked if they’d ever used an e-cigarette.

What They Found – People Who Think E-Cigs Are Safer Are More Likely to Vape

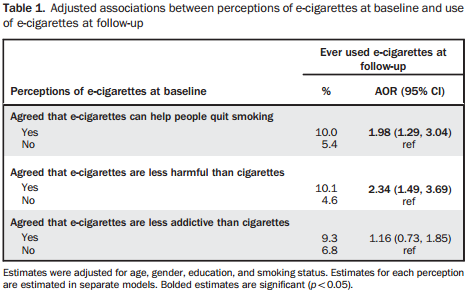

Surprise surprise, if you don’t think something is much of a risk you’re much more likely to get involved with it. The findings showed that respondents who thought e-cigarettes are safer than cigarettes were over twice as likely to have vaped, and a belief that they could help you quit was also associated with e-cigarette use. More of the participants who thought e-cigarettes were less addictive than cigarettes had vaped over the intervening year, but there was a smaller difference between the two groups of respondents in this case.

In total, 7.4 percent of the sample had tried e-cigarettes (rightfully classed as a measure of experimentation by the researchers – there is no evidence of regular use presented here), and unsurprisingly, the largest proportion of these came from those who were current smokers at the time of the first survey. 21.6 percent of the current smokers used e-cigs, 11.9 percent of former smokers and 2.9 percent of non-smokers.

So, Why All of the Concern?

Despite the fact that using something once is hardly the same as becoming a regular user, lead researcher Dr. Kelvin Choi still commented that, “The study showed that 2.9% of baseline nonsmokers in this U.S. regional sample of young adults reported ever using e-cigarettes at follow-up, suggesting an interest in e-cigarettes among nonsmoking young adults. This is problematic because young adults are still developing their tobacco use behaviors, and e-cigarettes may introduce young adults to tobacco use, or promote dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products.”

Firstly, e-cigarettes are a new gadget (and one used to consume a drug, no less), so a lack of interest from young adults would have been thoroughly baffling. If you’re counting as little as a single puff as use (which is assumedly the case), the fact that 2.9 percent of non-smokers had tried one is completely inconsequential. If anything, it seems a surprisingly low degree of experimentation among non-smoking young adults, and again, there is no evidence of continued use. To then go on and claim that “e-cigarettes may introduce young adults to tobacco use” is pretty absurd, because no such evidence was provided in the study, nor has it been documented elsewhere.

Dr. Choi also added in the paper’s Discussion section that, “This study also suggested that about 12% of former young adults smokers at baseline were re-introduced to nicotine through e-cigarettes. Future prospective studies including adults of all ages are needed to confirm these finding related to e-cigarette use among nonsmokers and former smokers, and to determine the role of e-cigarettes on relapse of smoking.”

Relapses aren’t ideal, but we have to live in reality, not a fantasy-world we create for ourselves in which addiction is easy to beat. Relapse is an accepted and seemingly unavoidable part of recovery from any addiction. Research on smokers trying to quit has shown that as many as 80 percent of those who try to quit relapse. Keeping that in mind, the fact that around 12 percent of former smokers used an e-cigarette is actually a good thing. If e-cigarettes hadn’t been available, is Dr. Choi insinuating that these young adults would have not relapsed at all? Because, as long as you aren’t willing to accept that absurd proposition, surely relapsing through e-cigarettes is better than going back to combustible tobacco? Sadly, the researchers didn’t see the need to include the number of former smokers who went back to smoking cigarettes over the course of that year, but the comparison would have been very illuminating.

How Not to Write a Fair Discussion Section for E-Cigarette Research

These choice quotes that have found their way into the media reporting provide just a hint of how one-sided the paper’s Discussion section is. When you’ve conducted a fairly inconsequential piece of research, it must be a little depressing to have to write up a discussion basically saying that, as expected, people are more likely to try something they think is safe. Instead, however, the researchers in this case decided to make out that their evidence is of significant importance by pretending that e-cigarettes are something to worry about.

The researchers acknowledge the positive conclusion from the 2011 review of existing evidence by Michael Siegel and Zachary Kahn, but other than that the Discussion section is a master-class in “cherry picking.” The section argues (with evidence) that experimentation with e-cigs isn’t associated with “intention to quit, making quit attempts or smoking cessation” (although the first study referenced above even concludes that they “may have the potential to serve as a cessation aid”). They also referenced a randomized trial on smokers with no interest in quitting (which found that 10.3 percent reduced their consumption of cigarettes after a year, and 8.7 percent quit altogether), but only pointed out that there was no difference in cigarette consumption or smoking cessation between those who were assigned nicotine and no-nicotine e-cigs – completely ignoring the overall quit rates.

This is very much the pattern throughout the paper’s Discussion – they point out that plasma nicotine content after e-cig use is similar to that found in smokers after a cigarette, offering this as evidence of similar addictiveness (although there is also evidence to suggest e-cigs aren’t as addictive as tobacco) and suggest that “development and perpetuation of nicotine addiction, pneumonia and congestive heart failure” are potential risks associated with e-cigarette use (based on adverse events reports). They suggest that since their study offers evidence that beliefs about the safety of e-cigarettes make usage more likely, the public should be educated on the lack of evidence for e-cigarettes being a cessation aid and the uncertainty of the risks associated with them.

Out of the collection of puzzling comments, the claim that pneumonia and congestive heart failure are potential consequences of e-cigarette use is probably the most baffling. It’s evident that some people really don’t like e-cigarettes, so why aren’t groups like ASH screaming this from the rooftops? Well, probably because, as the researchers on that study pointed out, “there is not necessarily a causal relationship between AEs [adverse events] reported and e-cigarette use, as some AEs could be related to pre-existing conditions or due to other causes not reported.” In other words, there are many potential reasons for this, and given that these reports are extremely, monumentally rare when the large number of vapers are considered, it’s just probably unrelated to vaping.

Conclusion – The “Beliefs” of Vapers Are Probably Right

So, what we have here is evidence of something pretty inconsequential (that people who agree with the existing evidence on the relative safety of e-cigarettes are more likely to vape) turned into fear-mongering newspaper-bait through a wildly misleading Discussion section. The study seems to have been conducted based on the implicit assumption that e-cigarettes are as bad as smoking, or are something to worry about for another reason, and then the researchers set about presenting evidence in favor of their position and their position alone.

It doesn’t matter that a recent clinical trial shows that e-cigs are at least as effective as patches, or that chemical and toxicological studies have shown virtually no risk at all in comparison to tobacco cigarettes, because the researchers clearly had a pre-existing opinion they needed to justify in order to make their suggested course of action – to “inform” people based on no evidence – appear more reasonable. It may be true that more research is needed, but unless the researchers have good reason to believe the e-cig studies to date are pretty much all wrong, then it doesn’t seem like the “beliefs” of the participants were wrong at all.

With that in mind, here’s a suggested alternate (translation: accurate) conclusion: young adults who agree with current scientific opinion – that e-cigarettes are safer than smoking and appear as effective at helping people quit as currently available options – are more likely to become vapers. This is primarily smokers, and the small amount of experimentation by non-smokers is realistically of little concern, given that no evidence to date suggests that any of them become regular users or subsequently take up tobacco smoking.