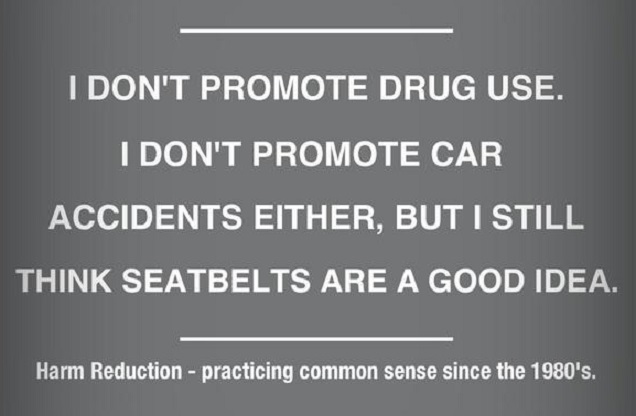

The worst thing about the continuous spread of misleading information and the manufacturing of misguided panics about vaping is the fact that e-cigarettes are really about harm reduction. Being opposed to harm reduction is a very bizarre position to take, basically equivalent to being in favor of harm. Although all available evidence indicates that e-cigarettes are vastly safer than smoking, unsupported statements give people the impression that the risks of the two products might not be so different at all, or at very least downplay the abundant benefits of switching to vaping. Arguments like “e-cigarettes aren’t absolutely safe,” “they contain cancer-causing chemicals” and “you’re still addicted” are ridiculous in the context of harm reduction, and this becomes pretty clear when you apply common anti-vaping arguments to other forms of harm reduction.

1 – “Vaping Isn’t Harmless” Applied to Seatbelts

Every time a study comes out supporting a potential (and usually fairly minor) risk from long-term vaping, anti-vaping groups and half-baked editorials come out with the firm allegation that “vaping isn’t harmless,” as if this is a reason you shouldn’t vape at all.

But you could easily say the same thing about seatbelts. The fact is that seatbelts don’t make driving completely safe: you can still die even if you’re wearing a seatbelt. Actually, seatbelts themselves can even cause injuries. A 2006 case report in the Southern Medical Journal points out that fractures to the sternum increased three-fold from the time seatbelt legislation was enacted to the date of the report, and seatbelts have also have also significantly increased the rate of intestinal injuries. It’s clear that “seatbelts aren’t harmless.”

The absurdity of making such a statement could scarcely be missed. Just in case it needs repeating: seatbelts save lives, reducing crash-related injuries and deaths by about half. So what is more important, an increase in some minor seatbelt related injuries or less people dying in car accidents? For the opponents of vaping – who don’t even have any substantial evidence of harm to back up their assertions (unlike our fictional seatbelt-hater) – the answer is apparently that the minor risks really are more important than the reduction in deaths.

Of course, they might argue that we shouldn’t go out on the road at all, but we need to at least make some effort to be realistic. In the real world, people drive and get in vehicles, and like it or not, some people consume nicotine. Doing so as safely as possible is just common sense.

2 – “You’re Still Addicted” Applied to Methadone

This is one of the most commonly-hear critiques of vaping: “you’re still addicted to nicotine!” they say, implicitly suggesting that harm reduction is pointless if you still maintain an addiction.

This criticism could be (and is) equally applied to methadone, “You’re still addicted to opioids!” In this case, the ex-heroin user, like the ex-smoking vaper, would rightfully respond “I was addicted anyway, and abstinence hasn’t worked for me.” But this doesn’t address the core issue with the statement: addiction alone is a pretty minor consideration in comparison to the other risks of heroin abuse. The reduction in mortality and reduction in HIV cases associated with methadone programs drives the point home pretty clearly: the benefits of not dying far outweigh the primarily-moral objections to any form of addiction.

Similarly, vaping is widely-expected to reduce the abundant health risks associated with smoking. If you oppose vaping because it doesn’t completely remove addiction (although there are indications it reduces it substantially), then you should also oppose methadone for the same reason. While the long-term evidence on the benefits of vaping isn’t yet available, for methadone the research is available, and the positive impacts are impossible to deny. The question is: does the moral objection to dependence on a chemical outweigh the huge health benefits of harm reduction?

3 – “Vaping Encourages Youth Nicotine Use” Applied to Condoms

You’d need to have been living in a box, underground and with your fingers in your ears to have missed the widespread concern that “vaping is leading to nicotine addiction in youth.” Of course, this hasn’t been convincingly demonstrated (since almost all regular youth vapers are smokers or ex-smokers), but the idea itself wouldn’t really stand up even if it had been.

What would you think if somebody said that by making sex safer, condoms actually promote promiscuity? Yes, such people really exist.

When the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested making condoms available to teens in schools, a poll found that two thirds of respondents didn’t think it was a good idea, with the idea that it would condone sex being among the most common reasons cited. Here’s a typically poorly-spelled and ridiculous comment, “If they give kids condoms thats basicly telling kids its ok to have sex and its not ok.”

In modern society these comments seem completely and hopelessly backwards, because of the fairly obvious benefits of having condoms. It might not be ideal for us (for parents, in particular) to acknowledge the fact that some teens are going to have sex, but the reality is impossible to avoid, and it’s obviously better to not get pregnant or contract an STD if you’re going to do that. You might want to blame condoms, but there are quite obviously other factors at play, and it will happen regardless of whether you try to make it as safe as possible.

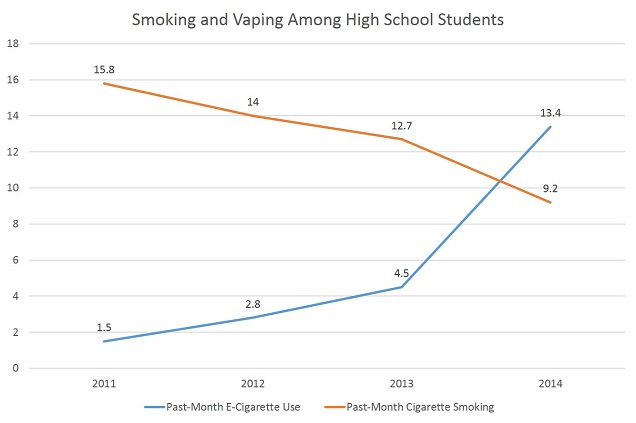

The statements about vaping encouraging youth nicotine addiction are pretty much identical – except nobody is proposing actively providing e-cigarettes in schools – and they fall prey to the same issue. News flash: kids sometimes start smoking. It’d be better if they didn’t, but that’s just how it is. For the opponents of safe sex, studies show that condoms aren’t linked to promiscuity in youth, and for the opponents of vaping, studies show that youth nicotine use is not increasing, and actually show that smoking rates plummet when vaping becomes more common. Does this evidence make a difference to those against harm reduction? Not really.

We should obviously try to prevent young people becoming addicted to nicotine in any form, but if they do, any sensible person would prefer them vaping than smoking, just like getting young people to hold off on having sex until they’re older would be ideal, but if they do, we better hope they use a condom.

4 – “Vaping Will Renormalize Smoking” Applied to All of the Above

The idea that vaping is bad because it will “renormalize” smoking is among my least favorite arguments against the technology, largely because this is something with no supporting evidence whatsoever (not even other evidence that could be misinterpreted as support). Smoking has been declining since vaping became popular, and then there is the glaring issue of vaping not being smoking.

This idiocy is easily revealed through comparisons to other forms of harm reduction, and in fact all three of the examples used above work. Because driving with a seatbelt looks almost identical to driving without one, would it also be fair to say that wearing seatbelts renormalizes driving without seatbelts? Because having sex with a condom is superficially similar to having sex without a condom, does that mean condoms renormalize unprotected sex? Anybody suggesting anything remotely like this would rightfully become the subject of intense, unrelenting mockery.

For vaping renormalizing smoking, the problems are compounded by the fact that e-cigarettes really don’t look all that much like combustible cigarettes, even if they once did. In this way, it seems like the statement “methadone normalizes heroin use” is a better example of the sheer level of stupidity required to make a similar statement about vaping. Coupled with the utter lack of evidence for such a position, these examples show that anybody who cries “renormalization” isn’t arguing based on science or logic, they’re likely just attempting to bad-mouth vaping any way they can, even if it means repeating baseless propaganda. Even ASH UK’s Deborah Arnott recently called the renormalization argument “bullshit.”

The same arguments, incidentally, also apply to the “e-cigs are a gateway to smoking” claims, usually made based on findings showing that those who’ve vaped are more likely to have smoked. It’s also undoubtedly true that those who’ve driven with a seatbelt are more likely to have driven without a seatbelt than those who’ve never driven at all, and that people who’ve had sex with a condom are more likely to have had unprotected sex than a virgin, or that those who’ve taken methadone are more likely to have taken heroin than people who’ve never taken methadone, so are these all gateway effects too?

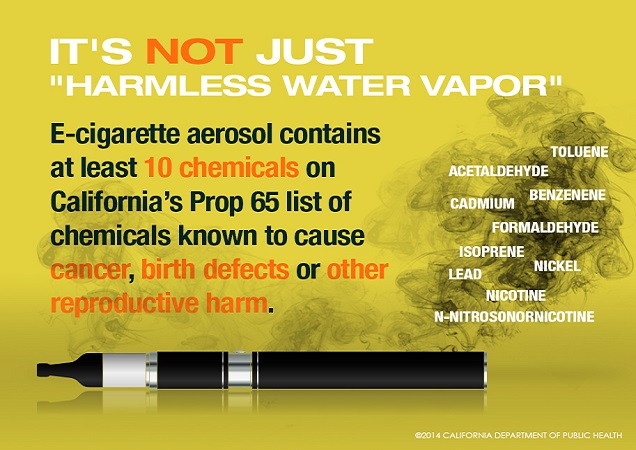

5 – “There are Carcinogens in the Vapor” Applied to Reduced Harm Diets

Potentially the most widely-repeated argument against vaping is that “there are carcinogens in the vapor,” with formaldehyde and tobacco-specific nitrosamines being among the most common examples. Of course, the amounts present (under ordinary vaping conditions) are much, much lower than the amounts of the same chemicals in cigarette smoke.

The absurd nature of discouraging vaping because of trace levels of harmful chemicals is revealed when you apply the same criticism to “reduced harm” diets. Although harm reduction isn’t commonly discussed in terms of diet, it can be easily applied to foods. Whereas overconsumption of high-sugar drinks and high-fat foods can be really bad for you, switching out that can of Coke for a low-sugar soda, swapping fatty meat for lean meat or ordering take-out less frequently is basically reducing harm through your diet – you still get the basic stuff you want, but reduce associated health risks. If you’d done this – and almost certainly lowered your risk of obesity and countless other health issues in the process – imagine how you'd respond to somebody coming along, acting all high-and-mighty, and pointing out “well, there is still sugar in that drink!” or “a low-fat meal still contains fat!”

Honestly, I’d laugh at them. Of course low fat doesn’t mean “no fat.” Obviously “low sugar” drinks still contain sugar. The key point is that a tiny bit of something isn’t the same as loads of it. If you’ve brought your sugar and fat consumption down, even though you’re still consuming fats and sugars, it’s undeniably a good thing. In the same way, reducing your exposure to nitrosamines by a factor of over 1,000 and reducing your exposure to formaldehyde around 10-fold is a good thing. E-cigarettes contain small amounts of these chemicals, yes, but the reduction in risk in comparison to smoking is huge, and the key point is that “the dose makes the poison.”

Although the diet comparison is perhaps a little unfair (after all, you need fats and sugars in reasonable amounts, unlike nitrosamines), the crucial fact is that a small amount of something bad doesn’t necessarily translate into real-world increases in risk. This is why low-nitrosamine snus doesn’t cause a measurable increase in mouth cancer risk, despite nitrosamines being present, and why NRT contains nitrosamines but nobody flips their lid about it.

Conclusion – Harm Reduction Isn’t Perfect, but It Works

Applying anti-vaping arguments to harm reduction approaches reveals them for what they are: senseless attempts to discourage something that could prevent a lot of illness and save a lot of lives. Depressingly, these examples have often revealed ridiculous things people do actually say about harm reduction on the whole, and the reason for this is simple. Harm reduction doesn’t seem appealing when looked at from an idealistic, “drugs are bad, mkay” standpoint. How can you possibly think it’s a good idea to give heroin addicts clean needles, to give junkies a legal source of drugs, or to hand out condoms to children? The answer is always, “because otherwise it will be even worse.”

The fact is that harm reduction isn’t really the perfect solution to these problems. It’d be better for heroin addicts to not inject at all and to not take opioids, and the most reliable way to avoid STDs is to not have sex. The reason harm reduction is necessary is because these approaches are not realistic: people do potentially dangerous things sometimes, like it or not.

Harm reduction is an ideal solution because it both respects people’s right to do something that isn’t ideal (if they want to) and makes whatever it is less likely to kill them or ruin their life. With vaping, methadone, needle exchanges, condoms, seatbelts or anything else, it really is that simple. Opposing such a move is a sure sign that your ideological opposition to the behavior or substance in question is clouding your judgment so much that it’s stopped you from caring about the well-being of your fellow human beings. And yes, even smokers are human beings.