We've all heard the arguments before. The anti-e-cig crowd cries that there hasn't been enough research on the effects, that the hypothetical issues with the manufacturing process could lead to catastrophic consequences for users or that they are as dangerous tobacco outright. This is by no means an exhaustive list of the claims which have been made about e-cigarettes, and proving each individual one takes time. Researchers like Michael Siegel and Carl V. Philips blog extensively to discredit the nonsense routinely flung around by pharmaceutical companies, anti-smoking groups and generally critical entities like the FDA. However, an old rationalist analogy from philosopher Bertrand Russell teaches us that it is the anti-e-cig crowd – not researchers who understand the amazing potential for harm reduction – are the ones who should be offering evidence.

We've all heard the arguments before. The anti-e-cig crowd cries that there hasn't been enough research on the effects, that the hypothetical issues with the manufacturing process could lead to catastrophic consequences for users or that they are as dangerous tobacco outright. This is by no means an exhaustive list of the claims which have been made about e-cigarettes, and proving each individual one takes time. Researchers like Michael Siegel and Carl V. Philips blog extensively to discredit the nonsense routinely flung around by pharmaceutical companies, anti-smoking groups and generally critical entities like the FDA. However, an old rationalist analogy from philosopher Bertrand Russell teaches us that it is the anti-e-cig crowd – not researchers who understand the amazing potential for harm reduction – are the ones who should be offering evidence.

Introducing Russell’s Teapot

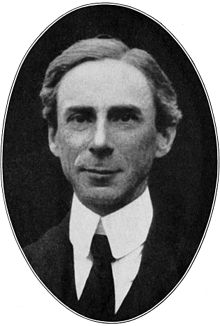

Bertrand Russell was a British philosopher, and a famous critic of religion, with one of his most famous published works being the 1929 “Why I am Not a Christian.” It was for this end that he created the famous teapot analogy, either referred to as the Celestial Teapot or Russell’s Teapot.

The analogy is pretty simple to understand. It’s a thought experiment (where you work through a hypothetical situation in your mind) designed to illustrate the critical issues of the burden of proof and falsifiability. Here’s a quote from the original essay it appeared in:

If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes.

But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is an intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense.

He continued along the same line (although, for his purpose he added that the existence of the teapot is indicated by sacred texts and taught every Sunday), claiming that his behavior – in believing in the existence of the teapot – would rightfully attract the attention of psychiatrists.

So how could we set about proving Russell wrong? Even if we scanned the entirety of the sky across the wide region between the Earth and Mars, the hypothetical proponent of the idea could simply claim that the telescopes were never pointed in the right direction at the moment the teapot was passing. We could even take it further, covering every single point in the sky simultaneously with monstrous telescopes, but the ideologically-charged believer would say that the telescopes simply weren't powerful enough to detect such as tiny China teapot.

If you were actually in an argument with a person like this, by now you’d probably be red-faced and agitated, clawing at any scrap of evidence to get them to admit that there’s no reason to believe in the teapot. But still, the conditions of its existence mean that you pretty much can’t prove it wrong. However, it’s patently obvious that the idea of such as teapot is completely absurd, and therefore that it doesn't exist.

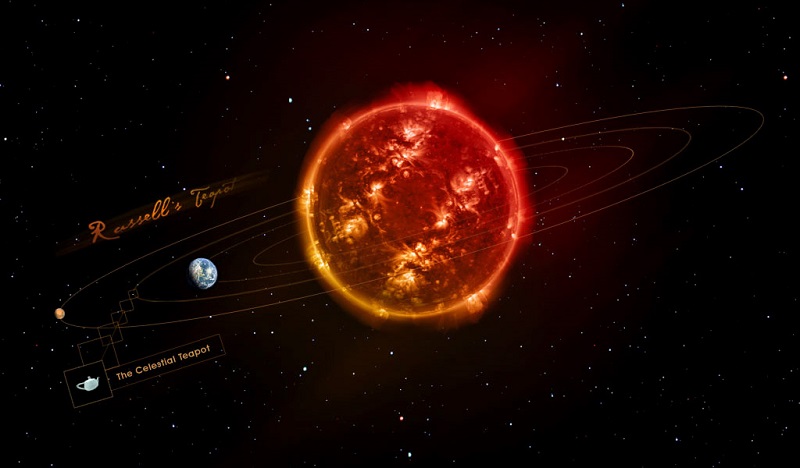

Falisifiability and the Burden of Proof

But how can we say this definitively? Well, we can’t. Every single piece of evidence presented by science is still not enough. There’s obviously a problem, because it can’t be a rationally flawless argument. In fact, there are two problems. One is that the argument cannot be falsified in principle (any scan of the sky could just be countered with a “the teapot is smaller than that,” at least down to the subatomic level), which is a black spot lingering over any argument.

The most important issue is the burden of proof. In this example, Russell postulates something which defies all common sense, since 1) we have never flung a tiny china teapot into orbit, and 2) if an alien species exists, the idea that they would have teapots or see the need to put one into orbit is ridiculous. So in situations like this, is it really right to make astronomers spend years searching for the proposed teapot? Of course not, because the burden of proof lies with the people making the extraordinary claims. The idiom is that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, or in Russell’s terms, the absence of evidence is evidence of absence.

How Does this Apply to the E-Cigarette Debate?

Although it was originally intended to discredit the notion of a deity, it is a valuable logical lesson which can apply to all types of arguments. It’s unfortunately common to see absurd propositions put forward – whether it’s that Obama is a Muslim or that the stars and planets determine your personality – and rational people have to thanklessly defend the truth in the face of an onslaught of stupidity. We all know about widely publicized FDA study, which created absurd rumors that all e-cigs contain anti-freeze or dangerous levels of carcinogens (both of which have been refuted), and the idea that flavored cartridges are designed to attract children. The problem is that lies are flung around as readily as excrement in a monkey cage, and even dedicated e-cig proponents and rationalists don’t have the time to effectively discredit each one.

There are some instances of unfalsifiable claims in the e-cig debate, and these are usually related to the intended purpose of e-cigs. Saying that the flavors are designed to lure children into smoking, or that they will attract non-smokers are ultimately unfalsifiable claims. You can say that since it’s illegal to sell e-cigs to minors or that e-cigs are actually made to help smokers reduce the risk they’re doing to themselves, but this won’t quell the debate. It’s steeped in vague terminology and hinges entirely on intent, which is pretty much impossible to prove one way or the other.

The vast majority of the e-cig debate is related to the burden of proof. Think of it in the simplest possible terms to understand why. People manufacture electronic cigarettes, selling a battery (like the one you’ll find in your laptop or cell phone) and cartridges with nicotine, propylene glycol and approved food flavorings inside. The nicotine has to be extracted from the tobacco plant, which means that until processes are improved, there will be trace amounts of nitrosamines and other chemicals in e-cigs. These have been documented thoroughly in research, and have been generally shown to be in similar quantities to FDA-approved inhalers, which is between 9 and 450 times less than you’d find in a tobacco cigarette.

It’s also known that nicotine is actually not the dangerous component of a cigarette, and that it doesn't cause cancer. Given these facts, and the fact that the same individuals do not criticize approved inhalers, any insinuation that electronic cigarettes are as dangerous as tobacco cigarettes is an extraordinary claim. Likewise, because research has been conducted, saying that we have no idea what’s in electronic cigarettes is also an extraordinary claim. Unless the people who claim this – like Cynthia Hallet of Americans for Non-Smokers’ Rights in the recent HuffPost Live debate – have reason to discount the numerous pieces of research into the constituents of vapor, then this is a perfect example of the misplaced burden of proof in the e-cig debate. Hallet carelessly tosses up these claims, only to have them refuted by Michael Siegel and Gregory Conley from CASAA, but she is the one who needs extraordinary proof.

This is by no means the only way in which this happens. Similarly, people claim that there is no proof electronic cigarettes can help people quit smoking, but that too has been shown in research to be the case (it’s even been established how they work to help smokers quit). The real point is that this could continue exponentially, with myth followed by debunking followed by myth followed by debunking ad nauseum. Bertrand Russell tells us that despite the amazing efforts of rational researchers, it is not their job to present proof of something which is merely common sense. The numerous pieces of research that have been done only serve to further push their claims into the realms of the extraordinary.

Putting it All Together

Coming to the conclusion that electronic cigarettes are considerably safer than tobacco or that they can help smokers quit requires nothing more than a basic understanding of their constituents and common sense. In a similar way, you only need a basic understanding of the solar system to discount the idea that there is actually an undetectable celestial teapot between the Earth and Mars. Claiming anything to the contrary is in direct violation of everything we understand, and therefore requires extraordinary evidence to possess even a scrap of credibility.

For reasons elegantly laid down by Bertrand Russell, any anti-smoking, pro-pharmaceutical or Big Tobacco representative who puts forward an argument against electronic cigarettes needs robust and compelling proof if they hope to be taken seriously. It isn't just because of their obvious conflict of interest; it’s because the things they say are often as absurd as the notion of the teapot. For this reason, in the HuffPost debate, the presenter jokes that “we should ban wearing pink shirts because the health effects haven’t been explicitly studied.” In the context of the debate, this is a modernized retelling of Bertrand Russell’s thought experiment.

The laws of logic are unchanging and unflinching. In terms of the implicit logic in the argument, if you fall prey to unsupported or unfalsifiable claims from those opposed to (or indeed, those in support of) electronic cigarettes, you must also accept numerous other notions on similar grounds. These include the celestial teapot, the possibility that bees possess superior mental powers which are undetectable by MRI machines, that aspirin causes ugliness and that when you’re sleeping (and no recording devices are in operation – they’re shy) electronic cigarettes sprout arms and legs, leap down your throat using a miniature bungee cord and surgically attach tumors to your lungs. Can you disprove any of these things? No. But there is no reason whatsoever to believe them without robust supporting evidence.