The potential risks of “second hand” e-cigarette vapor are of understandable concern for researchers, lawmakers and vapers themselves. Indoor vaping bans are instituted based on this potential danger, and – although we may doubt the level of risk – vapers, like any reasonable people, don’t want to harm anybody else.

A new piece of research has investigated the concentrations of nicotine, carbon monoxide and various volatile organic compounds after e-cigarette use, and compared them to those from a traditional cigarette. Although there has been research conducted on this topic before, this is the first to use a conventionally-ventilated and ordinary-sized room. The results attest to the extremely limited and quickly-dissipating concentrations of the tested components of e-cig vapor, and the fact that cigarette smoke is many times worse. However, some limitations with the study mean that further research is still needed in this area.

Summary

- Vapor was generated by smoking machine in one test, and experienced “dual users” in another. Dual users also smoked cigarettes so levels of nicotine, aerosol particles and volatile organic chemicals could be compared.

- Study used an average-sized room with controllable ventilation to account for potential variables.

- Nicotine was detected in all tests, but in 10 times higher concentrations following cigarette smoking.

- Cigarettes emit around 5.4 times more aerosol particles than e-cigarettes.

- Toluene was the only volatile organic compound detected in e-cig vapor, and the increase from the background levels in the room wasn’t statistically significant.

- 3.5 times more toluene was released from the cigarette, as well as three other volatile organic compounds.

- No carbon monoxide detected after e-cig use.

- E-cig vapor dissipates more quickly than tobacco smoke.

Testing Second-Hand E-Cigarette Exposure

The study was actually composed of two separate pieces of research: one investigating the levels of various chemicals generated from e-cigarette vapor produced by a smoking machine, and another investigating those levels when produced by a real-like “dual user” of both e-cigs and tobacco cigs. The study was based in Poland, and used three popular brands of e-cigarettes in the country for testing (Colinss Age, Dekang 510 Pen and Mild M201 Pen, with tobacco flavors on each). One brand (Colinss Age) had a drastic departure from the stated nicotine level (7 mg lower than the stated dose), but the others were within 1 mg of the stated 18 mg/ml concentration. They were all fully charged (for 24 hours – according to the methodology – which is a little excessive, to say the least) before the experiment, and tested in a room with a controllable ventilation system measuring just under 40 cubic meters.

Study 1: The first test used a smoking machine, and was intended to investigate whether any particular factors would have an impact on the amount of chemicals released into the air after e-cigarette use. It was composed of 12 separate experiments in which the machine generated vapor using a puff volume of 70 ml (within range of that reported in other studies) and taking a 1.8 second puff every 10 seconds. This isn’t a particularly realistic pattern (try that for thirty seconds to see why), but is based on that used in previous experiments.

They varied the ventilation level (high ventilation vs. restricted) and the pattern of emission (low and high – either 7 or 15 puffs), and tested each of these with the three brands of e-cig. The test period was two hours, with the first hour composed of testing background levels of the various chemicals in the room anyway, and the second hour involving two puffing sessions separated by 30 minutes. The seven puff test was intended to replicate the result if half of the nicotine released is absorbed into the user’s bloodstream (and therefore not exhaled).

Study 2: For the second experiment, they recruited five dual users – all men, with an average age of around 38 – and had them vape in two five-minute sessions separated by thirty minutes, then repeat the process but smoking cigarettes instead. This enabled a comparison between the emissions from the two, and the room was rapidly ventilated between tests to guard against contamination. As in the machine tests, background levels were taken prior to the test participants entering.

Both sets of tests measured the air for nicotine, aerosol particles, carbon monoxide, and 11 volatile organic compounds, including benzene, toluene, chlorobenzene and styrene. Of course, there would be ethical issues with subjecting people to these, so from these experiments the health impacts aren’t directly studied.

Results: Is Second-Hand Vaping a Concern?

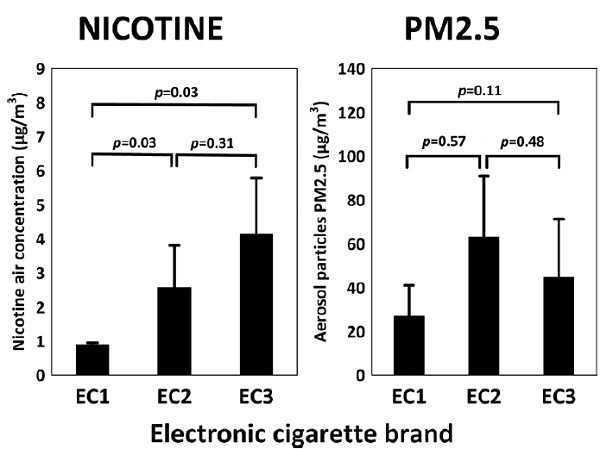

The researchers found an increase in the air’s nicotine concentration after either a cigarette or e-cigarette was used, as would be expected. The increase varied by brand, ranging from around 0.8 to 6.2 micrograms (millionths of a gram) per cubic meter.

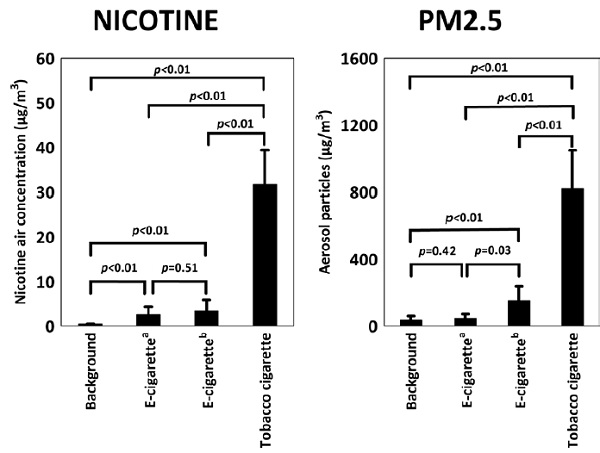

In the second experiment – involving direct comparison – when a cigarette was smoked, the nicotine concentration went up to 31.6 micrograms on average, compared to 3.3 for e-cigarettes. Cigarettes appear to release around 10 times more nicotine than e-cigarettes.

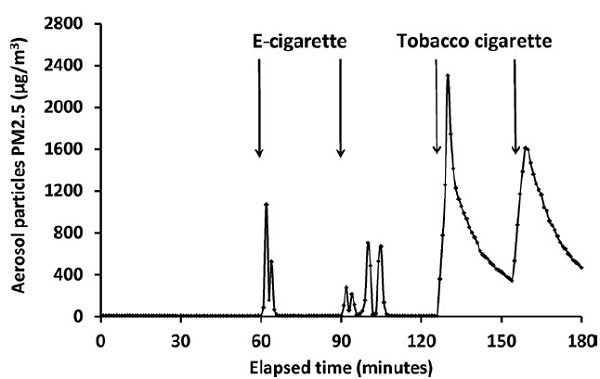

The concentration of aerosol particles from the smokers and vapers was also measured by the experimenters. The smoking machine generated an average aerosol concentration of 33 micrograms per cubic meter, and in the direct comparison test with dual users cigarette smoke produced around seven times more particles than was detected in e-cig vapor. However, this is only when the upper end of the possible concentration for a tobacco cigarette is used in the calculations; if both averages are used, cigarettes release 5.4 times more particles than e-cigarettes.

Carbon monoxide was not detected in the e-cigarette tests, but after two cigarettes were smoked in the room as part of the second experiment, the background levels rose by between two and three parts per million. In the volatile organic chemicals tests, only toluene was detected in e-cigarette vapor, and the level of increase from background levels wasn’t even statistically significant. This means it was small enough to possibly be caused by ordinary fluctuations – only rising from 3.8 to 4.1 micrograms per cubic meter. For cigarette smoke, four of the organic compounds were detected, with toluene in 3.5 times higher concentrations than in the vapor tests.

Toluene doesn’t sound too healthy, but considering the fact that the limit for it in drinking water is 1 mg per liter (roughly a thousand times more than was found per cubic meter of air in this study after vaping) and the OHSA sets the workplace exposure limit at 200 parts per million, there is very little to worry about; even without re-stating the fact that the increase wasn’t so much as statistically significant.

In addition, another finding was that the particle-count decreases much more quickly for e-cigarette vapor than for cigarette smoke, meaning that the already smaller concentrations of the chemicals are present in the air for even less time too. In other words, this study is good news for vaping.

Exposure Variation Between E-Cigs and Limitations

Aside from the expected finding that e-cigarettes are little to be concerned about when it comes to second-hand exposure, this study does offer evidence that there is some variation in the levels of chemicals created by different brands of e-cig. For example, second-hand inhalers will be exposed to more nicotine from some e-cigs than others, but this is still many times less than for tobacco cigarettes.

There were some limitations to this research, however. The main one is that only a small number of chemicals were included in the tests. For example, formaldehyde and acrolein have been detected in small concentrations in e-cig vapor, but they were not covered by this test. The fact that tobacco smoke only contained four out of the 11 volatile organic compounds shows that there are many relevant chemicals not considered by this study. However, the research to date supports this overall finding: e-cigarettes don’t release cigarette-like quantities of chemicals into the air, and there are much fewer of them.

In the discussion section of the paper, the researchers evaluate their findings, and also discuss implications for policy makers. They are generally cautious, saying that although only low levels of nicotine are found in e-cigarette vapor, there isn’t sufficient research into the effect of this on children, pregnant women and people with heart problems, for example. They also suggest that more research is required to determine what risk – if any – is associated with the concentrations of various toxicants after e-cigarette use. Afterwards, they briefly mention the risk of “renormalizing” smoking, wonder if e-cigarettes are reinforcing addiction and suggest that they’re promoted to evade existing smoke-free laws.

Conclusion

Overall, despite the needless, tabloid-esque panic towards the end of the discussion section, this study offers more evidence of the safety of e-cig vapor for bystanders. Bans on indoor vaping are generally built on the proposition that there is some risk inherent to second-hand inhalers, but this provides more evidence with which to challenge these unsupported assumptions. In future, similarly realistic studies testing for other chemicals will help to uncover more information on this topic, but for now, this is yet another investigation finding no cause for concern from e-cig vapor.

Photo credit: William A./WNYC

Read more on Second-Hand Vaping:

- Electronic Cigarettes Do Not Cause Second-hand Smoking

- Environmental Vapor Exposure Pose No Risk

- Review of Existing Evidence Confirms No Risk From E-Cig Vapor

- Study: Most E-Cig Vapor Poses No Risk to Heart Cells

- What Are the Typical Vapor Content of an Electronic Cigarette?

- Vaping is Not the Same as Smoking

- E-Cigs Not Found to Cause Lung Damage

- E-Cigs Do Not Cause Cancer