The New England Journal of Medicine formaldehyde study made a lot of headlines. Dire warnings that the cancer risk from vaping is bigger than the corresponding risk from smoking completely misread the study, which in itself was based on a rank misunderstanding of how vapers vape. The research was widely criticized, but the criticism was originally quite easy to brush off as armchair speculation. Unfortunately for the authors – and the NEJM – the criticism has been bolstered substantially by a new study that attempts to directly replicate the original findings. It succeeds, but only in dry puff scenarios. Combined with another study to address the issue, it’s safe to say the whole formaldehyde fiasco is based on bad science, and that calls for retraction were pretty well-founded.

The Original NEJM Formaldehyde Study

Most vapers know about the NEJM formaldehyde study already, but these are the basics. The authors were looking for formaldehyde hemiacetals (which are a combination of formaldehyde and PG or VG) in the vapor of an e-cigarette puffed at two voltage settings. At 3.3 V, there were no formaldehyde hemiacetals detected – meaning less than 0.1 μg per 10 puffs (1 μg = 0.001 mg). At 5 V, there was a lot more detected, 380 μg / 10 puffs. The authors went on to estimate the cancer risk (due to formaldehyde specifically – not the entire chemical mixture of smoke or vapor) from vaping at 5 to 15 times higher than smoking, based on the data from the high voltage test only.

The Obvious Problems Immediately Pointed Out By Vapers

But there was a little bit of information missing. What was the resistance of the coil? What atomizer was used?

The answers (only obtained by email correspondence with the authors – the paper doesn’t show this information to this day) show the big issues with the study. Firstly, the coil was a CE4 – a crappy top-coil clearomizer that was already obsolete when the study was published. Today, the CE4 is more of a historical curiosity than anything anybody would ever use, and there’s a good reason for that.

The top-coil design of the CE4 means that liquid has to be sucked up into the wicks against gravity to reach the actual coil. This takes a lot longer than it does on bottom-coil devices, where gravity helps rather than hinders. If you were – hypothetically, of course – to combine this with a stupidly high power setting and a relentless puffing regime, eventually there wouldn’t be enough e-liquid in contact with the coil and you’d get “dry puffs.” Every vaper knows this.

Cue the researchers with their fantastic idea to test it at 5 V. The coil had a 2.1 ohm resistance, which means that 12 W was going to the atomizer in the study, with 3 to 4 second puffs taken every 30 seconds for 5 minutes. This is a recipe for dry puffs.

This was pointed out to the authors via several letters, but it’s safe to say that they didn’t accept the criticism:

[Bates and Farsalinos] are entitled to speculate that use of the higher power setting in our work constituted ‘overheating’, and led necessarily to vapour characteristics for all humans (and e-cigarette fluids used) of ‘acrid’, ‘harsh’, and non-inhalable. However, that view seems highly tenuous, especially because of the very high concentrations of flavor chemicals we have found in many e-cigarette fluids. In fact, the tobacco industry has used flavorants to overcome smoke that is ‘acrid’ and ‘harsh’ for many years.

It couldn’t be that they don’t understand vaping, oh no. They did everything right, it’s just these promoters of vaping “speculating” in order to protect their pet cause.

The Impact of the Research

Before we move onto attempts to replicate these findings, it’s worth stopping to consider the impact of the original study. It has been cited 138 times in the scientific literature, and there are 386 news articles about it. The study itself has been viewed almost 300,000 times. If you only knew one thing about the potential risks of vaping, it would probably be this (or maybe popcorn lung).

This can’t be overstated: the study had a massive impact in the media and in society at large, and at least one person who’d otherwise have continued vaping returned to smoking as a result.

Of course this probably happened a lot more than this, and it’s impossible to estimate how many smokers decided not to switch on the basis of it. This would be understandable, since most newspapers stripped all nuance from the finding and simply reported as if vapers were more likely to get cancer than smokers.

Atomizer Choice Matters: The First Replication Study

For many people, the issue was put to bed when Dr. Farsalinos and his team published his first study attempting to replicate the findings of the original study. Crucially, in this study they recruited actual vapers (rather than depending on a smoking machine like the original research), and used two different wick setups to show how the specific atomizer affects which settings can be used. The authors got vapers to test each atomizer at 6.5, 7.5, 9 and 10 W and report when dry puffs were detected. They found that the single wick setup (like that in the original study) led to dry puffs at 9 or 10 W, but the dual wick setup never did.

When authors tested the aldehyde levels in the vapor at these settings, the results came as a surprise to precisely nobody who’s ever actually vaped at too high a setting for their atomizer. The levels of formaldehyde (and other similar chemicals) in the vapor drastically increased in dry puff conditions, increasing by anything from 30 to a massive 250 times the previous results. In usable conditions, formaldehyde levels reached a maximum of 11.3 μg per 10 puffs – 34 times lower than the results reported by the NEJM study.

But there were some slight limitations to this study. Firstly, the authors used an unflavored e-liquid, and many argued that flavorings would have masked the harsh “dry puff” taste, and that the results were therefore unreliable. Yet again, this criticism undoubtedly came from people who’ve never vaped, because you quickly learn that diminishing flavor is an early warning sign that dry puffs may be on the way.

Secondly, while the demonstration was convincing, it did use a Kayfun Lite Plus, rather than the CE4 like the original research. This isn’t really a downside to the study, but it does detract from its ability to directly refute the results of the original NEJM research.

The New Study: The Formaldehyde Scare Thoroughly Debunked

But now those limitations are no longer an issue. A new study from Dr. Farsalinos and colleagues goes even further, single-handedly demolishing the NEJM study and substantially bolstering the efforts to get the study retracted or corrected. This time, replicating the exact conditions of the original study was more of an explicit goal and the result is a more focused confirmation of the critical issues with the original research.

The authors got exactly the same equipment as was used in the original study: an iTaste VV, a CE4 atomizer and Halo’s Café Mocha e-liquid in 6 mg/ml nicotine. They also used the puffing schedule from the original research: 4 second puffs with 30 seconds between successive puffs. In the original study, they did this for five minutes using a smoking machine and tested for formaldehyde-containing molecules.

In the new study, a crucial new stage is added. First, 26 experienced vapers took 5 to 7 puffs from the device according to the puffing schedule. The screen was covered so the vapers didn’t know the setting they were on, and the researchers gradually increased the setting until the vapers identified dry puffs. The first setting used was 3.6 V, and then this was increased by 0.2 V for the next session (after a 5 to 10 minute break), and so on until dry puffs were detected. This allows the results obtained at different voltages in the testing phase of the study to be put firmly into context.

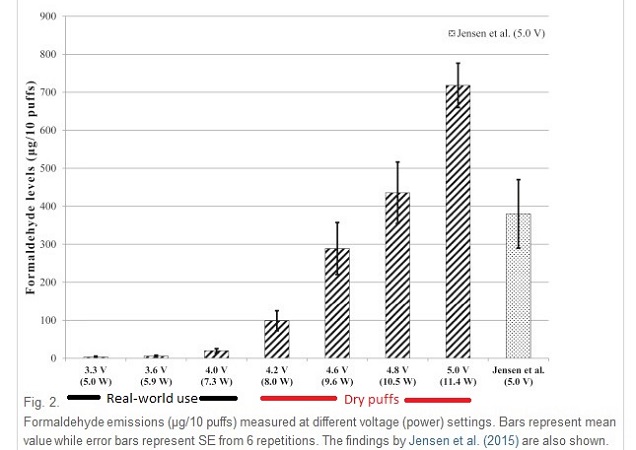

In the first portion of the study, 88 % of the vapers experienced dry puffs by 4.2 V (8 W), with the remaining three vapers reporting dry puffs at 4.4 V (8.4 W). Nobody was willing to vape the device at the 5 V (11.4 W) as in the original study. The researchers concluded that the upper end of real-world use for this atomizer was at 4 V (7.3 W).

The researchers then tested for formaldehyde. This image (a slightly annotated graph from the study) says it all.

At the upper end of realistic use, 19.8 μg of formaldehyde was detected for every 10 puffs. This was 36 times lower than the levels at 5 V, and about 19 times lower than levels reported in the original study. For a realistic “worst case scenario” calculation – analogous to the one in the NEJM study – the authors estimated that vaping for a day at the highest realistic voltage for a day would reduce your formaldehyde exposure by 32% compared to smoking 20 cigarettes. And – as we all know – formaldehyde is far from the only component of smoke that you reduce your exposure to by switching to vaping.

The discussion section of the paper explains the issues with top-coil clearomizers – which they advise both researchers and vapers against using – and make a strong restatement of the case to retract the original paper. They write:

[S]uch testing of e-cigarettes is not very different from overcooking food to the point of becoming an inedible piece of charcoal and then assuming that consumers would consume it and be exposed to the resulting carcinogenic compounds in their daily routine. Accepting that e-cigarettes are less harmful than smoking, such an omission could result in unintendedly misleading smokers into thinking that there is little to be gained by switching to e-cigarettes.

The NEJM Formaldehyde Study: An Obituary

So here lies the NEJM formaldehyde study. Concocted by researchers who’ve undoubtedly never vaped, who apparently neglected to research which settings to use prior to designing a study, and never thought to ask anybody who actually vaped to try their puffing schedule, any experienced vaper knew this day would come. We’d say we’re sad to see it go, but that would be an outright lie.

The huge stir it caused has left an indelible mark on the public perception of vaping. Thanks to overconfident researchers, the apparent disdain with which many in the research community treat the advice and criticisms of vapers, and journalists all-too-eager for another “so you thought these things were safe?” scare-story, a piece of non-news made its way around the world, misleading people into believing vaping was a bigger cancer risk than smoking.

People made decisions with serious consequences for their long-term health on the basis of a poorly-conducted study that has now been clearly demonstrated to bear no resemblance to the reality for vapers. Even though calls for retraction so far have fallen on deaf ears, for anybody who’s up to date with the science on e-cigarettes, the study is dead. It’s useless.

It turns out the vapers were right all along, and now there are multiple peer-reviewed studies to prove it.

Should The NEJM Formaldehyde Study Be Retracted?

The calls for retraction of the original study now have a much stronger basis to work from, and Clive Bates has already added a PubMed comment to that effect.

Guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics suggest that retraction should be considered by journal editors if “they have clear evidence that the findings are unreliable, either as a result of misconduct (e.g. data fabrication) or honest error (e.g. miscalculation or experimental error).”

This is evidently the case for the NEJM study right now. The results essentially have no bearing on reality, but the last paragraph (with the cancer risk calculation) explicitly makes inferences as if they apply to real-world users. I’m sure it was an honest error rather than fabricated data – after all, the new study got worse results than the original at 5V – but there is unavoidable evidence that the findings are unreliable. The simple fact is that the authors didn’t know what they were doing (a serious problem in no way limited to this one example), and that led to severe, crippling errors in the analysis.

Even if the editors don’t think retraction is justified – perhaps arguing that since the settings were available on the device, it’s a valid look at what happens when you vape at too high a setting – then a correction of some type definitely is. The guidelines state that a correction should be considered if “a small portion of an otherwise reliable publication proves to be misleading (especially because of honest error).”

It might not undo the scary headlines, and it probably won’t stop the article being cited in future either, but it’s abundantly clear that the cancer risk calculation is highly misleading. Given the impact the research had, issuing a correction should really be the bare minimum at this point from the NEJM. Ethically, misleading people about the risks of harm reduction is utterly indefensible, and scientifically, basing real-world risk calculations on profoundly unrealistic data is laughable.

The only question that remains is: will anybody in a position of power care enough to do anything about it?