A new study has led to some predictable, tiresome claims that e-cigarettes are a gateway to smoking, and it does a pretty good job of following the set of instructions I laid out previously for unscrupulous researchers looking to “prove” that e-cigarettes are a gateway to whatever the hell they want. In particular, this study commits a laughable error that already undermines two of the most recent studies purporting to show a gateway from vaping to smoking: focusing on students who’ve taken a single puff of an e-cigarette rather than anything approaching regular use.

So instead of covering all of the issues with this study – and research like it – which has already been done excellently by Clive Bates, Peter Hajek and Ann McNeill at the Science Media Centre, Carl V. Phillips and Michael Siegel, I’ll be focusing on this particular tactic, why it is so ridiculous and the three studies (we’re aware of) which fall flat on their face as a result.

One Puff and You’re Hooked? Why the Gateway Effect Requires Regular Use

To see the crippling issue with these studies, let’s consider three fictional teenagers who’ve experimented with vaping:

- Andrea tried vaping once in high school when a friend offered her a puff because she was curious about it. It made her cough, and she never tried it again. She wasn’t even sure if it had nicotine or not. Almost a year later, she was at a party and got a little drunk, and towards the end of the night a boy she liked offered her a cigarette. Hoping it'd make her seem edgy and cool – not to mention feeling the effects of the alcohol – she decided to give it a go. The nicotine made her feel dizzy and nauseous, and she never tried smoking again.

- Ben had never smoked, but he'd vaped a few times. He managed to buy a vape pen and some no-nicotine e-liquid, and used it for the flavors for a couple of days before a teacher caught him with it and took it off him. About 6 months later, his parents went through a messy divorce, and it affected him quite badly. He started getting rebellious. He tried marijuana, stole occasional beers from his dad and even tried cocaine. When a new, older friend offered him a cigarette, he smoked it, and was smoking every day before the end of the month.

- Charlotte had never been interested in smoking, but she’d heard that vaping was similar but much, much safer, so she thought she’d try it out. If it’s fun and doesn’t have much of a downside, she thought, why not? Smoking has way more risks than benefits, but vaping has so few downsides it could be a fun way to try out nicotine. After taking a few drags on a friend’s device and loving it, she bought her own and some 12 mg/ml nicotine e-liquid. She didn’t do it every day at first, but eventually she was vaping daily. It wasn’t long until the e-cig didn’t really satisfy her anymore. She wanted more nicotine, and after trying stronger-nicotine juices for a while, she eventually gave up and just bought a pack of cigarettes. The nicotine hit was much more intense; just what she was looking for. The vape pen didn’t do it for her any more, and she started smoking every day, whenever she could.

So, who is the gateway case: Andrea, Ben or Charlotte? It’s obviously Charlotte: she wasn’t interested in smoking, but the much safer nature of vaping convinced her to give it a try and eventually she got addicted to nicotine, then as a direct result of growing tolerance, she ended up smoking. Andrea never really started smoking or vaping, she just tried it out. Ben tried (nicotine-free) vaping before he started smoking, but the situation surrounding him starting smoking was nothing to do with vaping, it was more closely tied to a rebellious, experimental phase brought on by the difficult divorce his parents were going through.

Now, which of these teens would the newest study have classed as a “gateway” case? All of them. It doesn’t matter that Ben didn’t even vape nicotine, or that Andrea never started vaping or smoking by any reasonable definition. They had all vaped at least once and then went on to smoke at least once. That’s it, according to these studies and the catalogue of credulous rewrites of the press release currently making their way around the media, proof that e-cigarettes are a gateway to cigarettes.

Andrea’s case is the most ridiculous. For the study’s conclusion to be justified in a case like this, it would have to be that the one single puff of an e-cigarette was enough to change her for good, and mean that in a completely different situation almost a year later, she said “yes” to smoking where she would have otherwise said no. Also, the fact that she didn’t even start smoking is treated as equivalent to the other two cases, in which the teen started smoking regularly.

Ben’s is only slightly less ridiculous. For the “gateway” interpretation to be valid, it would have to have been his few days of nicotine-free vaping which led to his taking up smoking, rather than the psychologically challenging time he was going through when his parents broke up that led to him using various substances. Vaping would have to be damn-near magical to have caused this rather than the much more pressing factors occurring at the same time.

The key thing that differentiates these cases is the regular vaping of nicotine-containing e-liquid coming before the regular smoking in Charlotte’s case. There are still some problems with how likely this is (would she really go from something she only tried because it was safer to something vastly more dangerous, all for the same substance?), but ultimately it fits the mold most of us would imagine when we think of a gateway from vaping to smoking.

Clive Bates’ definition of the gateway effect goes:

There is harmful gateway effect if young people who would not otherwise smoke take up vaping and, because of vaping, they develop a consolidated smoking habit that they would not otherwise have developed.

In order for studies to be able to differentiate between an Andrea, a Ben and a Charlotte, they need to establish that the youths take up vaping (i.e. regular vaping), that they end up with a continuous smoking habit and that they made the transition between the two because of vaping. Although becoming accustomed to a smoking-like behavior could be an explanation for this, the most obvious and plausible way it could happen would be if they became addicted to nicotine through vaping, and this led them to smoking.

As we’ve covered before, this really doesn’t seem to be happening. Not only is the rate of regular vaping among non-smoking teens incredibly low to non-existent, the only study to address the question of nicotine use found that most teens don’t consume nicotine when they vape. So the crucial first stage of the gateway progression – getting addicted – doesn’t appear to be particularly likely. Perhaps this is why studies hoping to find a gateway effect often treat the issue as if one puff is all you need – otherwise they wouldn’t have a very big sample to work with at all.

And, for a final look at the problems with this approach, imagine that in Charlotte’s case, she previously had no interest in smoking because she’d tried it before and didn’t like it, rather than just basing her view on the risks. If that was the case, she wouldn’t have been classed as a gateway case by this study and ones like it, even though it doesn’t change the important part of what happened to her at all. This further underlines the issues with the simplistic “first vaping, then smoking = gateway effect” argument.

Three Flawed Studies; Three Sets of Misleading Headlines

The “one puff” approach to studying the gateway effect first appeared in a study by Adam Leventhal and colleagues back in August 2015, which led to the usual round of headlines and plenty of criticism from supporters of vaping. The biggest issue was that the study, with the “one puff” approach to classifying youth vapers, captured a lot of experimenters, and it’s no surprise that they would be more likely to experiment with smoking too. Clive Bates’ post on it was entitled, “JAMA paper finds some adolescents experiment with stuff – so what?” and pretty much gets the point across. The researchers did try to control for important factors, but how good a job they did is questionable.

The second study with this glaring error had more problems, since even using their ridiculously broad definition of e-cig “use” (i.e. one puff and you’re a vaper), they still only ended up with a sample of 16 never-smoking “vapers” to work with. They continued, regardless, and (surprise, surprise) found that these 16 teens were proportionally more likely than the 678 who’d never vaped to have smoked a cigarette (again, at least one) in the following year. Again, the problems with the study were quickly pointed out.

And now we have another, with a different lead author but Adam Leventhal among the credited authors too. He was the lead author on the first study of this type, and in that study’s limitations section, observed:

A limitation of the study is that e-cigarette use was measured only as any use and product characteristics (eg, nicotine strength and flavor) were not assessed. Thus, whether a specific frequency or type of e-cigarette use is associated with the initiation of combustible tobacco could not be determined.

This study focuses solely on initiation outcomes; however, future research should evaluate whether e-cigarette use is associated with an increased risk of escalating to regular, frequent use of combustible tobacco.

In other words: “we know it’s silly to base this study on vaping at least once and smoking at least once, but that’s just the way we did it.”

You’d have thought that with this new study, they could have opted to address that issue. In fact, they were perfectly capable of doing that – we know this because they said so in the description of their methods. They wrote:

At each survey, participants were asked whether they had ever tried e-cigarettes, cigarettes, cigars, pipes, or hookah and the number of days each product was used in the past 30 days. (emphasis mine)

Strangely, though, nowhere in the paper are the results of this final question reported. Despite the same authors identifying this as an issue in the previous study, they still kept the focus on “ever” vaping rather than current or regular vaping. So how many of the supposed gateway cases in this study were actual gateway cases? We have no idea. And, oddly, this time the authors didn’t report the focus on ever-use as a limitation. They mentioned that they didn’t ask about nicotine use as a limitation, but a better approach would have been actually finding out if the “vapers” did use nicotine.

Regardless of all of the issues, the study (like all of the others) had its desired effect, producing headlines like “Vaping teens more apt to move on to regular cigarettes: U.S. study.” Michael Siegel can be seen at the bottom of that Reuters article pointing out the big issue with the study, but in this age of social media – where headlines matter way more than content – the damage has pretty much already been done.

Gateways are Rare; Exaggerated Studies are Common

The truth is that some teens probably will start out using nicotine by vaping and then go on to smoking. The key word, though, is “some.” Based on the other evidence we have, we can be pretty sure it won’t be too many.

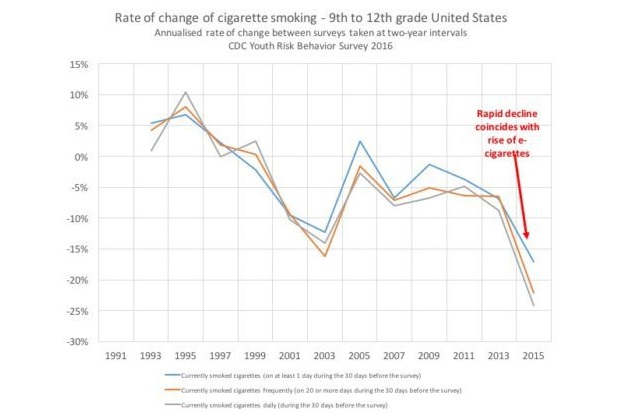

Even though moving from something less dangerous to something much more dangerous doesn’t make too much sense, some will undoubtedly do it, but so far we can be pretty confident that more teens (and adults) are moving towards the safer option and away from the more dangerous one, because the smoking rate is rapidly declining (quicker than previously, as shown above). Even if more reliable research finds that vaping does lead to smoking for some teens, population-level evidence shows that many more youths are quitting smoking than are taking it up. That won’t stop studies and headlines like this, but it at least gives supporters of vaping some ammunition for the ongoing fight against anti-vaping nonsense.