A new study from CDC researchers has revealed that vaping is used by more smokers trying to quit than FDA-approved methods like patches, gums and medications. Unsurprisingly, this is being treated as if it's bad news. The authors of the study write:

There is no conclusive scientific evidence that e-cigarettes are effective for long-term cessation of cigarette smoking. E-cigarettes are not approved by the FDA as a smoking cessation aid. FDA-approved medications have helped smokers to quit, in many instances doubling the likelihood of success. Finally, we found that most smokers who are switching to e-cigarettes or “mild” cigarettes are not switching completely. These smokers are not stopping their cigarette smoking.

There is a lot to unpack here, but the implication is very clear: they are not happy that smokers are switching to vaping more often than they’re using one of the pre-ordained methods. After having apparently dedicated themselves to promoting the uninformative message that vaping “isn’t safe,” I suppose it’s obvious why they aren’t entirely happy.

Their approach just isn’t working.

If you’re in the world of public health, in which people’s choices and preferences are less important than whether they make choices you approve of, smokers’ decision to ignore anti-vaping misinformation is deeply troubling. “How can we get them to stop vaping?” You might think. “What can we do to encourage them to use FDA-approved methods?”

But let’s step outside of the world of public health and take a look at the issue objectively. Let’s depend on evidence rather than gut reactions when we’re trying to determine if this is news to be celebrated or feared.

The authors might not be happy about the finding, but anybody who wants the best for smokers really should be.

The Study: What Are the Most Popular Methods of Quitting Smoking?

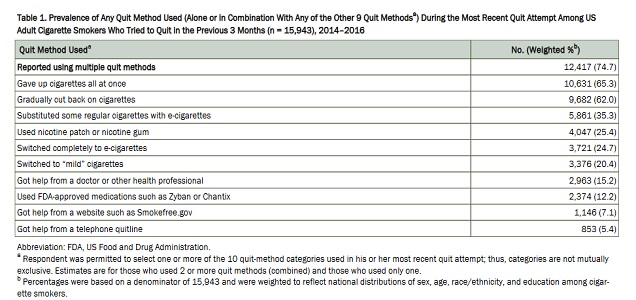

The study (available in full for free) had a pretty simple design. People were surveyed online between April 2014 and June 2016, with the group chosen to be nationally-representative. In the end the authors focused on the 15,943 current smokers (meaning they’d smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lives and still smoked regularly) who had attempted to quit in the three months prior to being surveyed. If they’d attempted to quit, the researchers asked which method or methods they’d used.

Around three-quarters of smokers used multiple approaches in their most recent attempt to quit, and the remaining quarter only used one approach.

The most common quit methods used were trying to quit all at once (65%) and trying to cut back gradually (62%). This basically means that the most commonly-used approach was “cold turkey” quitting.

For the remaining approaches:

- 35.3% of smokers attempted to cut down using e-cigarettes

- 25.4% used nicotine patches or gums.

- 24.7% attempted to switch to vaping completely.

- 20.4% of the smokers tried to switch to “mild” cigarettes, which don't reduce harm in practice.

- 15% got help from a doctor or other health professional

- 12.2% of the quitters used medications like Zyban or Chantix

- 7.1% used a stop-smoking website

- 5.4% phoned a quit-line

How Smokers Who Used a Single Approach Tried to Quit

For those who only used one method in their quit attempt, the picture was much the same. 4.3% of smokers tried to cut down by vaping, and another 4.3% tried to quit entirely by vaping. Patches, gums, medications, mild cigarettes and advice (from doctors, websites or quitlines) were less popular, listed in descending order of popularity. Again, cold turkey was the most widely-used approach.

Why Vaping’s Popularity Matters

The study itself might not seem particularly important, but it is a sign of something very important: smokers like vaping. Over a third of them cut down smoking by vaping, or at least attempted to, and almost a quarter attempted to switch completely. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough information provided to work out the percentage who tried vaping overall, but it must be more than 35%, maybe 40% or even more.

Compare this to Zyban or Chantix, used by only 12.2% of smokers who try to quit. Vaping is over three times more popular than FDA-approved medications. While we vapers may instinctively scoff at the use of medications to quit smoking, they do work, increasing your chance of quitting by two to three times compared to a placebo treatment.

Nicotine replacement therapies also increase your chance of quitting, and are available fairly widely, but only 25.4% of smokers used them. Unlike with vaping, the authors didn’t separate these into attempts to cut down and attempts to quit entirely. Overall, the evidence on NRT suggests that they’re effective about 8% of the time – it isn’t much, but still better than going cold turkey.

In both these cases, it’s safe to say that we have a lot more hard evidence confirming that they’re useful for quitting than we do with vaping. It’s probably safer to use a nicotine patch or gum than to vape. It’s understandable why somebody taking a cautious approach might prefer people to use an approved method.

But that depends on ignoring what they want to do. No matter how much you try to change people’s behavior, they still make their own choices. You can’t force them to quit your way. This study shows just that: most choose to quit without support and very few use the most evidence-based approaches.

Doing the Math: Vaping is Creating More Quitters than NRT and Medication

Say there are 10,000 smokers attempting to quit. The study tells us what they’re most likely to do, and other evidence tells us how likely they are to succeed. For the sake of simplicity we’ll use the figures for the smokers who only tried one method. Although it’d be more difficult to fit into a neat example or to actually work out with the study’s results, the same basic conclusions will apply to those who use more than one approach too.

From 10,000 smokers trying to quit using just one approach:

- 435 will start vaping with the intention of quitting smoking altogether

- 435 will start vaping to cut down on their smoking

- 316 will try a nicotine patch or gum

- 158 will try a medication.

So with these baseline numbers who try each approach, we can estimate how many will successfully quit.

Estimates for the effectiveness of vaping vary, but we can use an unrealistically conservative quit-rate of 8% (the same as NRT) because it doesn’t affect the core point. You’d expect that the quit-rate would be lower for smokers just intending to cut down rather than to quit, but there’s not much to base this on. Since this is a cautious estimate, we can just cut the success rate in half (to 4%) for those just intending to cut down. We’re just looking for ball-park estimates, not precision.

Based on evidence cited earlier, smokers attempting to quit with medications are successful roughly 15% of the time.

Putting this together gives a conservative estimate of:

- 52 vapers successfully quit.

- 25 patch or gum users successfully quit.

- 24 medication users successfully quit.

This tells suggests that vaping will create more quitters than patches, gums and medications combined. They may be FDA-approved, and some could even be more effective approaches than vaping, but this is much less important than the choices smokers make about how to quit.

If we use a more optimistic estimate, things look even better for vaping. The Royal College of Physicians’ report on e-cigarettes suggests (on page 116 of the PDF, for anybody playing along) that vaping combined with support from a stop smoking service is about as effective as medication.

So we can put vaping on the same 15% success rate, for a less conservative estimate, and stick with half that rate (7.5%) for those just intending to cut down. In this more optimistic case:

- 98 vapers successfully quit.

- 25 patch or gum users successfully quit.

- 24 medication users successfully quit.

This would suggest that twice as many smokers quit by vaping than by using medication, patches and gums combined. While the specifics are definitely debatable, the overall conclusion that more smokers quit using vaping than FDA-approved treatments is hard to doubt.

Of course, these numbers are still awfully small when we’re starting with 10,000 smokers. The reason for this is that cold turkey quitting is incredibly popular. Of the original 10,000, a huge 8,419 would attempt to quit cold turkey, and even with a dismal 1-in-20 success rate, this would lead to 421 successful quitters.

The overall lesson is really simple: no matter how effective your intervention is; it doesn’t help many people if it isn’t very popular. Conversely, even something less effective can help more people if it’s more widely-used.

This might almost seem like an endorsement of cold turkey. And of course if that's what you want to try, that's great and you should go for it. Many smokers are successful that way and you could be too. But the big problem is that you’re more likely to be successful if you try anything other than cold turkey, so the more smokers who use another approach; the more successful quitters there will be.

Medicines aren’t popular enough to make a dent in the number of smokers opting to quit cold turkey. Patches and gums are widely-available and widely-recommended, but they’re still less popular than vaping. In a country like the US, where anti-vaping misinformation leads smokers to drastically overstate its risks, vaping still being the most widely-used quitting approach is a sign that it could really make a difference.

The Paragraph of Spin: How the Researchers Downplayed the Importance of Vaping

The real headline from this study is that vaping is responsible for creating more quitters than NRT and medications combined. This is great news. Cold turkey still might beat it on raw numbers of quitters, but the more smokers deciding to vape instead of quitting cold turkey, the better.

So how did the researchers interpret the results? They treated vaping like an unwelcome distraction from the pre-approved pharmaceutical approaches. They weren’t concerned about the substantial number of cold-turkey quitters; they were concerned about the number doing something that’s undoubtedly more effective than that.

Their spin is summed up by the paragraph quoted in the introduction, so it’s worth taking each point in detail.

There is no conclusive scientific evidence that e-cigarettes are effective for long-term cessation of cigarette smoking.

This is a very carefully-worded statement. “There is no conclusive scientific evidence,” not “there is no scientific evidence.” The latter version would be false, because the best evidence we have suggests that e-cigarettes really do help smokers quit.

More than that, the plausibility of vaping being an effective approach to quitting smoking is so high that you’d struggle to argue against it even if we had no evidence at all. Nicotine helps smokers quit in patches, gums and inhalers, so why would it not help if it was delivered through an e-cigarette? It makes no sense.

But the truth is that the hard evidence we have so far on the quitting question genuinely is limited. There aren’t many clinical trials and the other evidence has issues too, though it’s mainly down to too few studies and small sample sizes. So when they say it isn’t “conclusive,” they’re not entirely wrong, but it’s a decisively misleading way to explain the evidence on the issue.

E-cigarettes are not approved by the FDA as a smoking cessation aid. FDA-approved medications have helped smokers to quit, in many instances doubling the likelihood of success.

This is a red herring. As noted above, vaping helps people quit, and any reasonable estimate puts it as at least as effective as FDA-approved nicotine patches and gums. Sticking to the “not FDA approved” line makes it seem that e-cigarettes aren’t effective, and is yet again disingenuous in the extreme.

Finally, we found that most smokers who are switching to e-cigarettes or “mild” cigarettes are not switching completely. These smokers are not stopping their cigarette smoking.

The big problem with this claim is that the researchers didn’t find that most smokers weren’t switching completely. They found that most smokers who’ve tried vaping but still smoke didn’t intend to switch completely. By focusing the study on current smokers who’ve recently tried to quit, the data specifically excludes anybody who was successful. This likely skews the balance towards smokers who were only intending to cut down.

We know that many smokers not originally intending to quit who try vaping do end up switching completely. We might not be able to estimate the precise number, but it’s definitely not fair to assume that everybody who originally intends to cut down doesn’t wind up quitting as a result.

When more data from this survey is available (there were follow-up surveys not discussed in this paper), we’ll be able to get a much better picture of whether they’re “stopping their cigarette smoking” in the long-run.

Plus, even if they don’t quit, is cutting down somehow a bad thing?

And the less said about the fact that they lump vaping in with “mild” cigarettes the better. “Mild” cigarettes still involve the combustion of tobacco, and all the harmful chemicals that gives rise to. Vaping doesn’t and consequently drastically reduces your exposure to these chemicals. Pretending that these are in any way equivalent is beyond a joke.

In one paragraph, the authors of the study aimed to sweep aside the most obvious conclusion to draw from this research, denigrating existing evidence and being transparently one-sided in where they applied scientific scrutiny.

What the Paper Really Means

Any realistic interpretation of this study is hugely positive for vaping. With increasing popularity among smokers trying to quit, it’s almost certainly having a bigger impact on smoking rates than medications and NRT. At the moment, cold turkey is still the most popular approach to quitting, but if anything is going to change that for the better, it’s vaping.

It's demonized at every turn and people vastly overestimate its risks, yet results like this show the massive potential vaping has and hint at the size of the effect it's already having. Just imagine how things could improve if the continuous stream of misleading messages and sensationalized headlines was replaced with a much-needed dose of the truth. How many of the smokers who attempt to quit cold turkey would give vaping a try instead if they were accurately informed that it is over 95% safer than smoking and quite effective for quitting? How quickly would the smoking rate decline then?

Just being honest about vaping could save lives.