A new study aims to further the anti-vaping agenda by combining two of the sources of the most indignation about the technology: advertising and the children. Stanton Glantz called the study “direct evidence that e-cig TV ads are recruiting kids to nicotine addiction,” but, as with most things that come out of his mouth, this is pretty much complete nonsense. “Direct evidence” it definitely isn’t – they didn’t even follow up with the youths to see if they tried vaping – and “recruiting kids into nicotine addiction” should probably be “making teenagers marginally more likely to say they’ll try vaping, if they watch four of the most effective ads consecutively.”

Do Ads Impact Teens’ View of and Willingness to Try E-Cigarettes?

The study (available in full for free) had a pretty simple methodology: split a bunch of youths into two groups at random, assess their baseline characteristics and willingness to try vaping, show one group a series of four e-cig ads (from brands like Blu and Njoy), and then ask this group how willing they are to try vaping a second time. The other group was shown the ads afterwards, and then all of the participants were asked their whether they agreed with several statements about e-cigs, including “you can use e-cigarettes in places where smoking is not allowed,” “e-cigarettes are a safer alternative to regular cigarettes” and “people can use e-cigarettes without affecting those around them.”

The ads were specifically chosen because of their likeability and perceived effectiveness, with a pretest study looking at responses to 13 ads (airing between 2013 and early 2014) from youth and then choosing the four which were liked the most and seen as the most effective for the study. So not only does this test use an unrealistic scenario involving viewing four consecutive ads, the specific ads are pretty much the best ones available.

In total, there were 3,665 participants aged 13 to 17 in the study. There were some minor differences between the groups: the “experimental” group (who viewed the ads before the questionnaire) already appeared more interested in trying vaping and included slightly more smokers than the control group.

The purpose of the “control” group isn't exactly clear, either: comparing pre-ad and post-ad scores from the same group wouldn't introduce this potential bias into the study, and the control group wasn't even given any sort of control intervention (for example, viewing neutral information about e-cigarettes) that would provide insight into whether it was the advertisement itself or simply being primed to think about vaping that impacted on participants' willingness to try it.

What They Found – Even After Viewing Ads, Teens Aren’t That Interested in Vaping

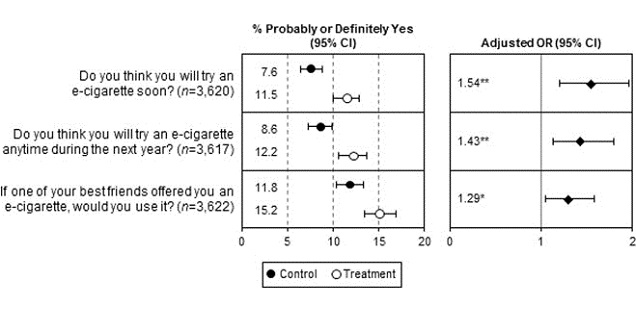

The authors report that those who viewed the ads were significantly more likely to be interested in trying vaping later down the line (controlling for differences in smoking status): they were 54 percent more likely to say they think they’ll try vaping soon, 43 percent more likely to say they think they’ll try it in the next year, and 29 percent more likely to say they’d try it if offered by their best friend, all in comparison to the group who didn’t see the ads before answering the questions. For critics of vaping like Stanton Glantz, this shows that ads “move youth who have never used e-cigarettes toward taking them up.”

However, the actual rates of positive responses to the questions about trying vaping paint a very different picture. Before viewing any ads, 8.3 percent of those in the treatment group said they’d try vaping soon, and after viewing the ads this increased to just 11.5 percent: meaning that 88.5 percent still weren’t interested in trying vaping, even after viewing the four most effective e-cigarette ads one after the other. Apparently, only 3.2 percent of all the youths in the study were affected by the ads at all, and even then, we don’t know how many said they’d “probably” try vaping and how many said they’d “definitely” try it – these responses were lumped together and not reported separately.

For the other questions, the results were pretty similar: the percentage saying they’d vape in the next year went from 9.4 to 12.2 percent (a 2.8 percent increase) and the percentage saying they’d vape if offered by their best friend went from 12.5 to 15.2 percent (a 2.7 percent increase). So, even the highest result in the study shows that 84.8 percent of youths have no interest in trying vaping, with the possibility that up to 4.6 percent of the others are current smokers (who were found to be 28.7 times more likely to want to try vaping).

In fact, the study makes it abundantly clear that a best friend offering an e-cigarette has a bigger role to play than advertising (even if you watch four of the best ads in a row), with 12.5 percent of the experimental group (or 12.3 percent averaged across both groups) saying they’d vape if offered by a best friend before viewing any ads: compared to 11.5 percent (saying they'd vape soon) and 12.2 percent (saying they'd vape within a year) after viewing ads but without their best friend offering.

The remainder of the results, although painted as showing “more-favorable attitudes” towards vaping after viewing ads, simply showed that ads made youths more likely to hold accurate views about vaping. For example, the teens who viewed the ads were more likely to correctly respond that you can vape without affecting those around you and that e-cigs are a safer alternative to regular cigarettes, even though the majority still didn’t agree with both of these points.

The authors do acknowledge some of the limitations to their study, but the biggest one – viewing four of the most effective ads consecutively – is laughably brushed aside with the comment “e-cigarette TV advertising viewed by U.S. adolescents is aired at media levels in excess of those in the forced exposure of this study.” The reference points to a study finding that youth “exposure” to e-cig ads increased from 2011 to 2013, but offering no evidence that viewing four ads in a row is even remotely likely.

The Non-Issue of E-Cigarette Advertising, Exaggerated

The authors conclude that “continued unregulated e-cigarette advertising will contribute to potential individual- and population-level harm.” This is clearly the desired take-away, and Glantz gladly follows the authors’ lead by pointing out that neither the FDA nor FTC has proposed prohibiting e-cig ads. It wouldn’t be much of a surprise if they did, though, and this is precisely the type of over-hyped junk science that would be used to justify such a move.

The problems with the manufactured concern about e-cig ads are obvious after reading the study: not only did the unrealistic battery of advertisements have a pretty small effect; the impact of peer influence is clearly much bigger. The crucial point is that – even with e-cig ads airing on TV – there is no evidence of regular vaping among non-smoking youth.

However, limiting the ability of e-cig ads to attract adult smokers on the basis of a completely negligible effect on teens probably would lead to individual and population-level harm, by protecting combustible cigarettes from competition.