A new study has been pounced on by many interested parties – such as the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids – who claim it provides hard evidence that e-cigarettes are a gateway to smoking. However, as with pretty much any study claiming to show this so far, it’s so severely limited – in various ways noted by Clive Bates, Michael Siegel, Konstantinos Farsalinos, Carl V. Phillips and others – that it really shows no such thing, and is destined to merely serve as ammunition for those hoping to demonize vaping in any way possible. In brief, the study really shows that “teenagers who experiment with things go on to experiment with other things.”

So, instead of providing a summary of the findings and going on and on about how vaping once in your life and then going on to smoke at least once is not a “gateway effect,” I’ll be using this study as a blueprint for how to “show” e-cigarettes are a “gateway” to pretty much anything: binge drinking, marijuana, cocaine, heroin and virtually any substance (or dangerous activity) you want.

(This post is also inspired by Carl V. Phillips' paper on methodological issues in gateway studies, which I didn't originally give sufficient credit to, and is well worth reading if you're interested in a more rigorous look at why the available evidence doesn't support the existence of gateway effects for THR.)

1: Don’t Define The Gateway Effect

Without a definition, the gateway effect is basically un-testable. If you were trying to scientifically test the theory, you might be tempted to explain that the classic vaping-to-smoking gateway effect is “somebody who wouldn’t have smoked otherwise getting addicted to nicotine through vaping and later switching to regular smoking for a more efficient dose.” DO NOT do this. The authors of this study didn’t bother, which is handy, because otherwise it may have quickly become obvious that this study was incapable of detecting such an effect.

2: Get the Timing Right

If you want to show a gateway effect, the best time to strike is when some experimentation has occurred but just before the bulk of it will occur. The researchers in this study recruited their sample of teens when they were 14, because, in their words, “the first year of high school is a vulnerable period for initiating risky behaviors.”

3: Choose an Area Where Vaping is Common

The core observation at the root of gateway hypotheses is that those who experiment with substances often try them in a particular order. This order isn’t related to some magical properties of specific substances; it’s largely down to the fact that some substances are more common than others. If someone is going to take heroin, they probably won’t jump right to it, because how the hell do you even find some heroin? Chances are they’ll stumble across tobacco (or nicotine in another form), alcohol or marijuana first.

The key to “showing” a “gateway effect,” then, is to make sure that the thing you’re intending to claim is a gateway substance is common, and ideally more common than the thing you’re wanting to show it’s a gateway to. Using this logic, you can say marijuana is a gateway to “hard” drugs (in the US), but also that hard drugs a gateway to marijuana (in Japan). In the (full) sample used for this study, 10.5 percent had ever smoked cigarettes, 12.6 percent had tried cigars and 15.2 percent had used hookah, but 18.6 percent had tried vaping. Admittedly, any combusted tobacco use (23.1 percent) was more common than vaping, but the fact that vaping was the most common individual method of nicotine use was enough to encourage the intended conclusion to arise from the data.

4: Use Your “Gateway” Substance to Separate the Experimenters

There are fundamental differences between a teen who’s tried vaping and one who hasn’t. Why would somebody try something that looks like smoking? It’s either because they just love the flavors so much or because they’re already interested in smoking and possibly other substance use. So the very decision to select a group based on their propensity for using substances sets up a key difference between the two groups that will be exploited throughout the study.

In this study, out of the 2,530 never-smokers, just 222 (8.8 percent) had ever vaped. But – thanks to our ill-defined gateway hypothesis – we have the perfect excuse to focus on this small minority of never-smokers.

5: Don’t Cast Too Small a Net – One Puff is Enough

The real goal is to cast a wide net so you capture as many experimenters as you can. Thankfully, we haven’t defined gateway, so we can easily just say “ever vaped, even one or two puffs” is the initial exposure we’re interested in. We don’t need to say recently, and we don’t need to emphasize that this doesn’t even tell us if any are even possibly addicted to nicotine (which looking at daily or even weekly vaping would). This variable simply collects all the teens interested in experimenting with nicotine, and probably a lot of those more generally interested in any substances.

6: Confirming the Presence of Nicotine is Helpful, But Not Required

To help out with the goal of capturing as many of the experimenters as possible, there is no need to even ask if nicotine was present in the e-cigs the teens tried: the authors of this study didn’t bother. The benefit is that this widens the net even further, including yet more risk-taking teens in your “e-cig user” group and thereby helping you blame even more subsequent substance use on vaping, even if nicotine had nothing whatsoever to do with it. Don't be worried about readers picking up on this: simply don’t address the fact that not all e-liquids contain nicotine and most people will just assume that they do. Of course, it would be more convincing if you did specify that they tried nicotine, but the inherent assumptions people make about vaping and nicotine allow your conclusions to have pretty much the same impact either way.

(Thanks to Norbert Zillatron in the comments for adding this point, which I’d originally missed)

7: Ignore Confounding Variables (Or Don’t Control For Them Well)

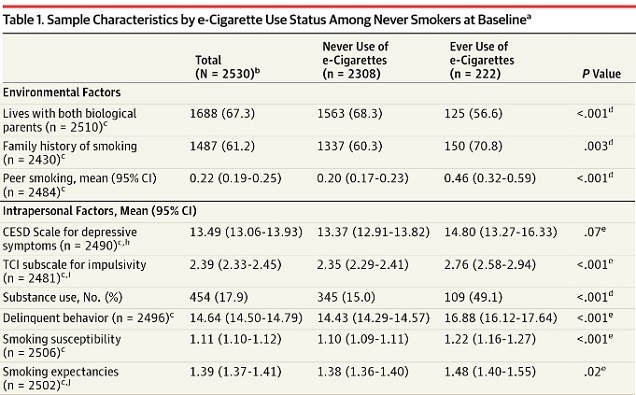

Since we’ve specifically looked for experimenters, we shouldn’t be surprised if our resulting groups are quite different. In this study, they definitely were. Among the never-smokers, those who’d ever vaped were more likely to have friends who smoked, a family history of smoking, to be impulsive, to use drugs (a massive 49 percent of the teens who’d vaped had used drugs compared to 15 percent of the non-vapers), to show delinquent behavior, to be susceptible to smoking and to expect to smoke.

The authors made some effort to control for these potentially important factors, which helps to (but doesn’t definitively) rule out their contribution to the findings. This is an admirable move from the researchers (if you really want to show a gateway, it’s better to just not bother), but as Clive Bates points out, choosing the right variables to take into account and giving them appropriate weight in the analysis isn’t easy, so it could well be that something important has been missed out.

In this study, the never-smokers who’d vaped by the start of the study were 4.3 times more likely to have smoked at follow-up than the never vapers, but when these important factors were taken into account, it dropped to 2.7 times more likely. If they’d controlled for more relevant factors (or done it better) it would have undoubtedly shrunk a lot more.

In his paper on gateway effects, Carl V. Phillips details how devious scientists actually interested in the truth can use the data to look at the effect of the authors' choice of variables and their weightings on the results. However, you better hope that nobody does that with your data, because he writes that the authors' claim that they properly controlled for important factors in this study is “very much not convincing.”

8: Make it Longitudinal (If You Must)

The easiest way to “show” a gateway is also the most transparent: when you simply look at your sample at one point in time, you’d expect that the teens who’d vaped would be more likely to have smoked too. This could go either way – smokers trying to reduce harm or vapers progressing to smoking – but if you’re really eager to “find” a gateway effect, you can forget about the more likely option and just pretend that the vapers progress to smoking. You can even do the same thing with binge drinking, if you like, because teens who try smoking or vaping are probably more likely to drink or take other drugs too. The problem is that most people can see through this strategy, because it’s so monumentally stupid that only people like Stanton Glantz would try it.

Another plus-point for this study was that the researchers actually looked at the sample over time – following up at 6 months and 12 months after baseline – so they could at least say the vaping came before the smoking. Good scientists will point out that just because vaping came before smoking doesn’t mean it caused the smoking, but luckily, we’re only trying to convince the public and a few politicians here, and nobody listens to scientists unless they have something newsworthy to say.

9: Choose Your Poison

So now we have a nice situation set up: we’ve cordoned off the experimenting teens from the more sensible ones, and we can follow them over time to see what they get up to next, blaming whatever happens on vaping. Smoking is the obvious one, but these kids are experimenters, so you can give it a go with pretty much anything. There’s already been a claim e-cigs lead to cocaine abuse, and smokers are more likely to use cocaine and other drugs too. So you can choose whichever substance you want: just pick one that’s reasonably common, because experimenters will experiment with whatever is available.

10: Exclude People Who’ve Already Tried the Substance

The really annoying thing about trying to claim that undirected experimentation is a definite progression from one substance to another is that some free-spirited teens will do the exact opposite and undermine your conclusion. In fact, that’s exactly what happened in this study – teens who’d smoked at baseline were three times more likely to have vaped at follow-up. Do the same thing as the researchers did to minimize its effect: any teens who’d already smoked at baseline were simply excluded from the main analysis, so the participants could only move in one direction. You’ve already selected for experimenters, but this allows you to narrow the field further by only focusing on experimenters who are yet to try a common substance despite having tried something similar.

11: Don’t Worry About How Often They Do It

If you’d actually defined the gateway effect, people might be expecting you to find people getting addicted to the end-point drug in question. In this study, people expect that the teens progressing from vaping became regular smokers. But the authors were smart: these teens are experimenters, so why create a bottleneck at the end that only those who get addicted can squeeze through?

Simply define the end-point as ever trying the substance in question, even once; better known as continuing to experiment. Those who’d tried vaping in this study could have simply tried a single puff of a cigarette but quickly realized that they were right to try vaping instead of smoking (because vaping tastes better and is unlikely to kill you) and then never touched a cigarette again. Similarly, a teen who tried vaping might think they’d enjoy cocaine, so could give it a try when offered by a friend, but not really enjoy it and never try it again. However, they’d still be classed as “progressing” to the substance in your results, so they’d look like gateway cases.

12: Tweak Your Model as Needed

If you’ve foolishly tried to control for too many of the variables that really determine which teens experiment with cigarettes, alcohol or other substances, then just mess about with the weightings or included confounders in your model. You can just include one cut of the data and pretend that’s what you meant to do all along.

13: Acknowledge the Flaws in the Approach, But Not Too Noticeably

You can’t get away with blatantly deceptive practices that easily in science, but that’s what “discussion” sections are for. Be honest (ish) about how stupid your approach is in the discussion section, but barely mention it (if at all) in the press release. Nobody bothers reading the study before writing about it, and even if they check it out, they’ll probably only read the abstract. You can have your cake (being all honest and science-y in the paper) and eat it too (so the limitations are glossed over when it’s put to the public).

Write something like “This study focuses solely on initiation outcomes; however, future research should evaluate whether e-cigarette use is associated with an increased risk of escalating to regular, frequent use of combustible tobacco,” and add that “Further research is needed to understand whether this association may be causal.” That should cover your back.

14: Mission Accomplished

Once it’s published, all you have to do is sit back and watch the unsubstantiated nonsense fly. Everybody wants an excuse to bash vaping – because it’s just not newsworthy if e-cigs are a safe and effective harm reduction approach – so if you throw the bait out there, they’ll take it.

Conclusion – There is No Gateway!

In case it needs clarifying: there is no evidence of a gateway effect from vaping. Teens who experiment with nicotine in one form will probably do it in another form too, and if they experiment with one substance they’re more likely to do the same with another one at some point in the future. Without actually identifying even a single never-smoker (ideally who wouldn’t otherwise have smoked) who started using nicotine through vaping and then progressed to regular smoking, there is no hope for the gateway hypothesis at all. Finding one such case would be a start, but to really push the idea, there would need to be a lot more than that.

And this study – even though it’s better than many others (and doesn't do all of the thing listed above) – still really doesn’t cut it.